CultureMap Exclusive

After nearly two years behind bars, Menil graffiti tagger talks prison, parole and his Picasso attack

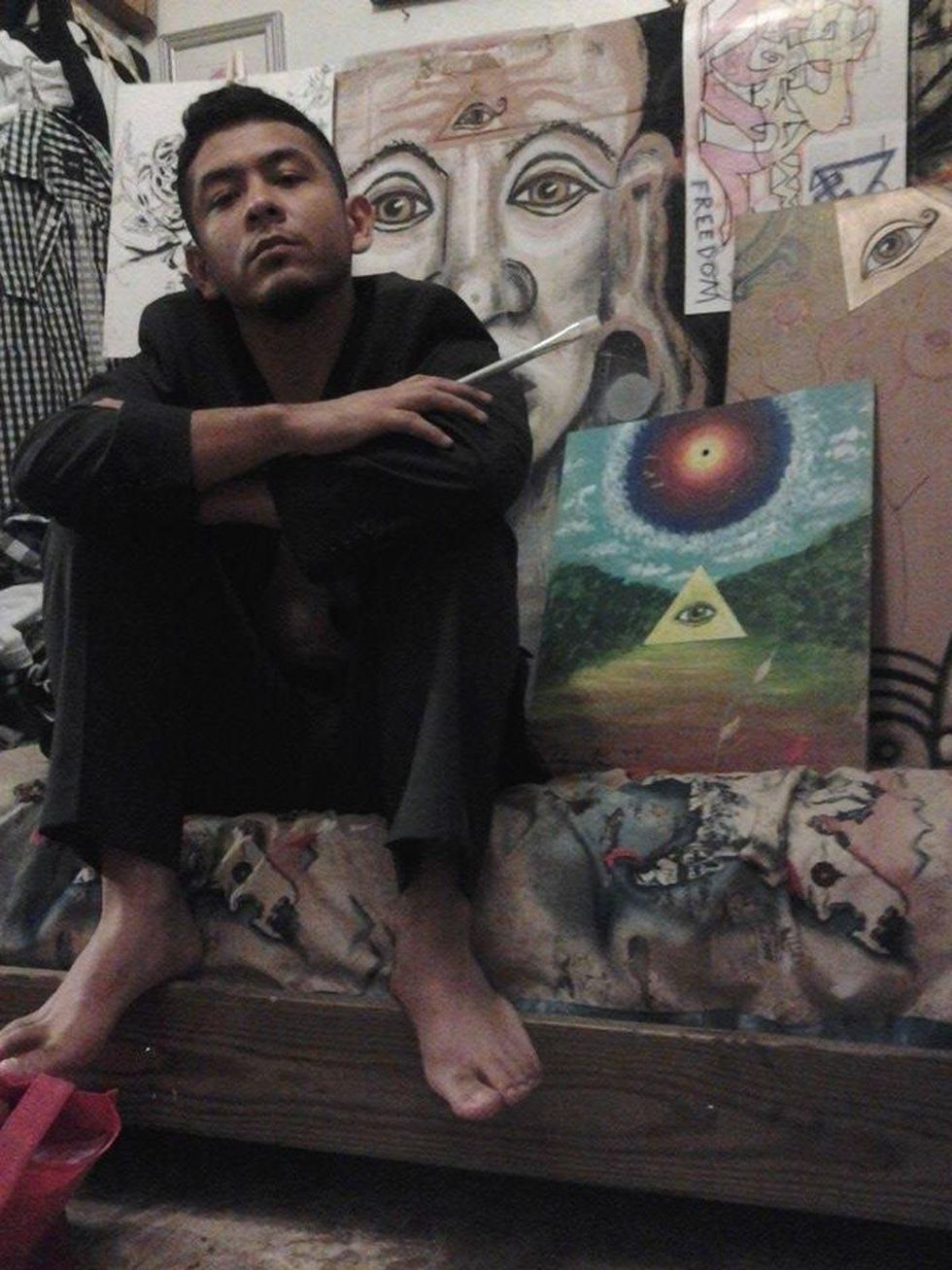

More than two years after spray-painting a Picasso at the Menil Collection, Uriel Landeros says he still receives the occasional piece of hate mail. But fresh from a 20-month stint in the Texas prison system, the 24-year-old artist wants to make one thing clear . . . He doesn’t regret a thing.

In a candid conversation with CultureMap — his first with media since getting paroled in late September — the former University of Houston art student argues that the June 2012 Picasso incident was never a publicity stunt or brash act of vandalism, but rather a carefully-planned performance piece about social justice.

“I wanted to do something positive,” he explained by phone from his parent’s home in the Rio Grande Valley.

“I wanted to do something positive . . . I wanted to find a way to raise aware ness.”

As noted in a previous CultureMap interview, Landeros aligns himself with the pro-democracy Occupy movement. When the global protest phenomenon began to dissipate in early 2012, the young painter began to consider ways to keep that energy alive.

“There was all this stuff going on in the news . . . Arizona immigration laws, Catholic church abuse, WikiLeaks and big elections in the U.S. and Mexico. I wanted to find a way to raise awareness.”

He says the attack was not specifically directed at the Menil itself, but at the systems of capitalism, colonialism and cultural exploitation that he feels undermine both the art world and a fully democratic society.

“I’ve learned from studying Picasso and Dali that art is a tool. Fuck painting, fuck drawing. It’s about the message, so use it.”

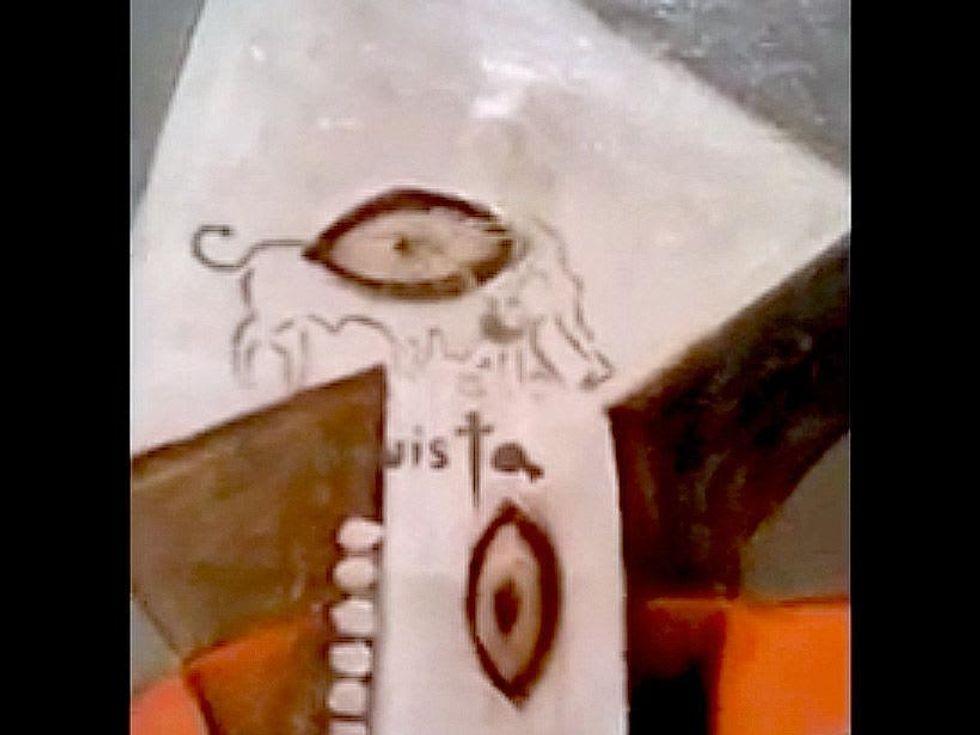

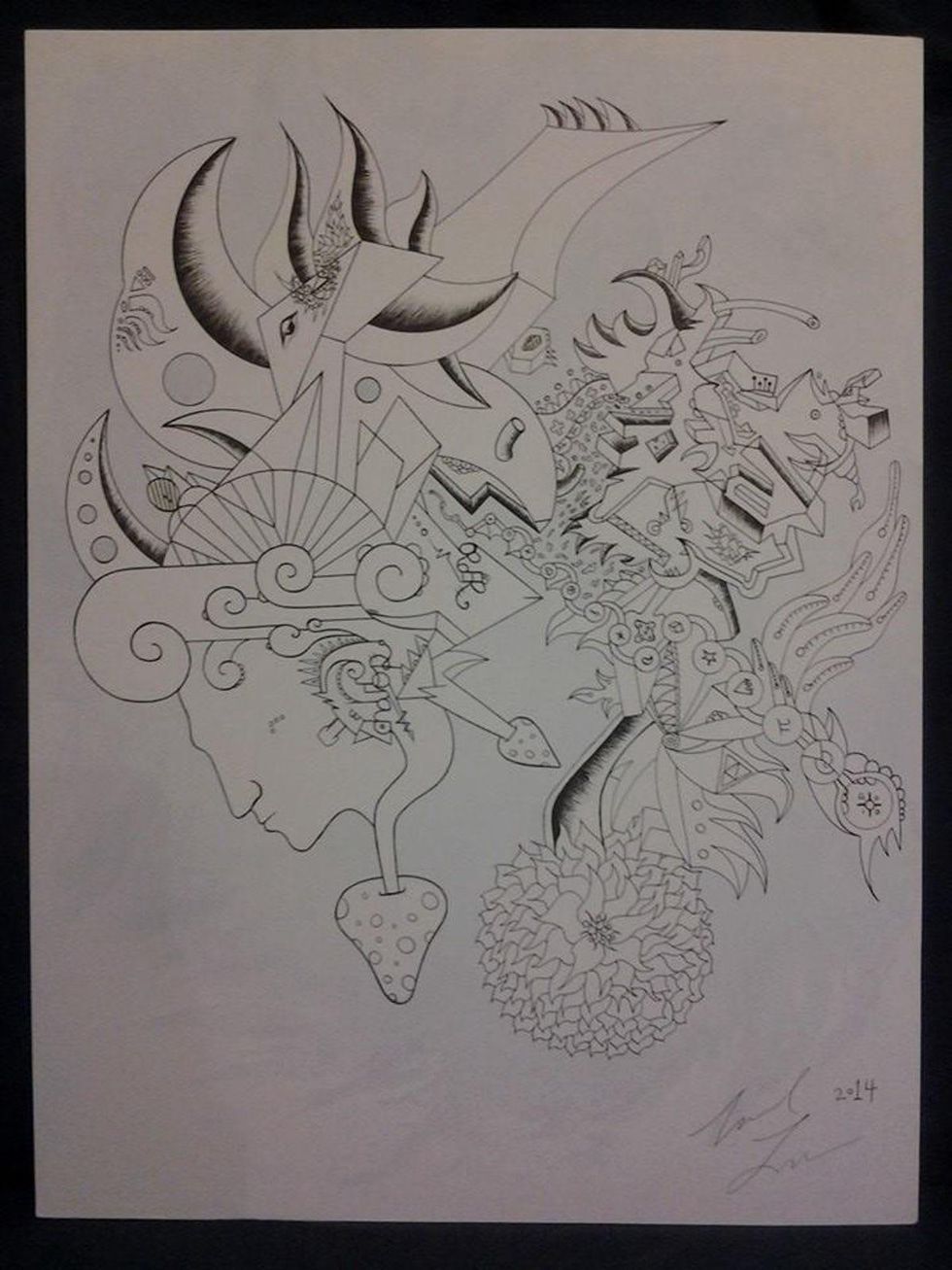

The stencil

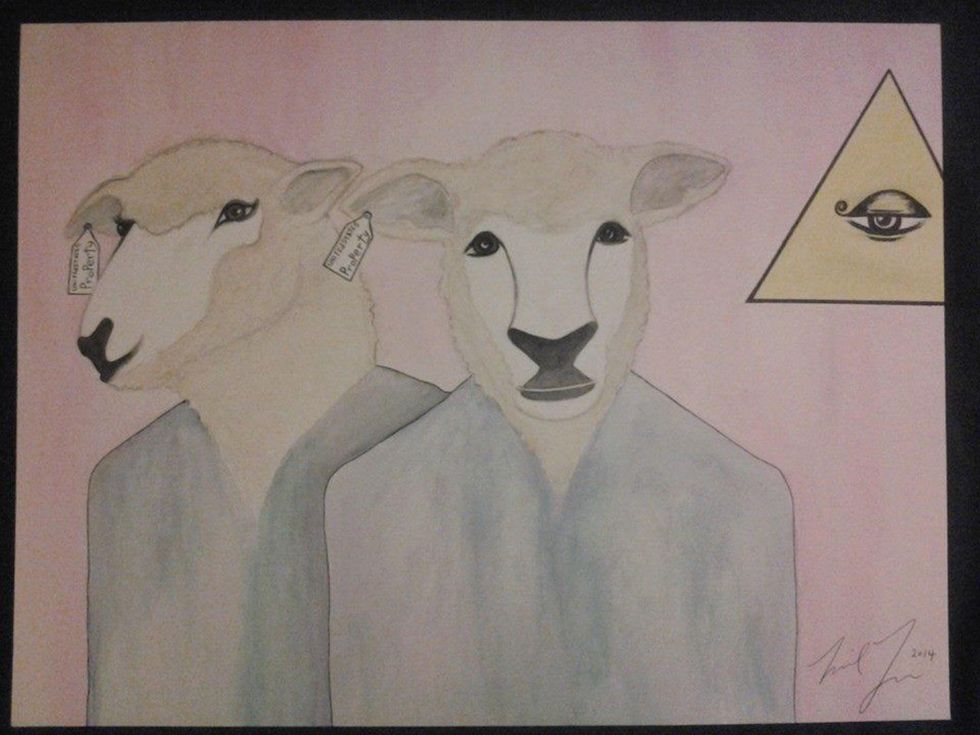

To both literally and figuratively make his mark, Landeros says he searched for an image that fused the Occupy ethos with his own Mexican heritage. In the end, he created a stencil of a bull and matador, along with the word "conquista."

“Somehow, at the time, I connected that image of bull with this situation going on around us. It represents Wall Street, which is connected to the Occupy movement, capitalism and the one percent.

“Anybody can make a stencil and do it. But to get away with it without anyone seeing you?”

“It also represents my own background and the Mexican tradition of bull-fighting, which is originally from Spain . . . And then there’s Picasso — even people who don’t know much about art know Picasso. He’s from Spain too, which again connects to the whole conquista thing.”

After planning his attack, Landeros tagged Picasso’s Woman in a Red Armchair on a quiet Wednesday afternoon in June 2012 (watch the video). Crossing the border into northern Mexico, he evaded authorities for six months before turning himself in the following January.

“Anybody can make a stencil and do it. But to get away with it without anyone seeing you? I feel like that was the true art of it.”

Amid press coverage from CNN to the New York Times, Landeros pled guilty to third-degree felony charges for causing damage estimated between $20,000 and $100,000. He was given a two-year sentence.

“I was thinking they’d throw me in county jail for six months . . . not prison for two years.”

Menil conservators fully restored the painting, which was later selected by acclaimed Belgian artist Luc Tuymans to appear in his 2013 portrait show Nice. Officials at the museum declined to comment on Landeros’ release.

Prison and beyond

While his time in some of Texas’ toughest prisons was no picnic, Landeros notes that life behind bars helped him better define himself as both an artist and activist.

“There’s all this shocking stuff in prison that keeps you awake at night. There were riots and gang fights all the time. A guard got stabbed,” he recalls. “I just focused my energy on art to create a positive energy in this negative place. It helped me get through the whole experience.”

“I just focused my energy on art to create a positive energy in this negative place.”

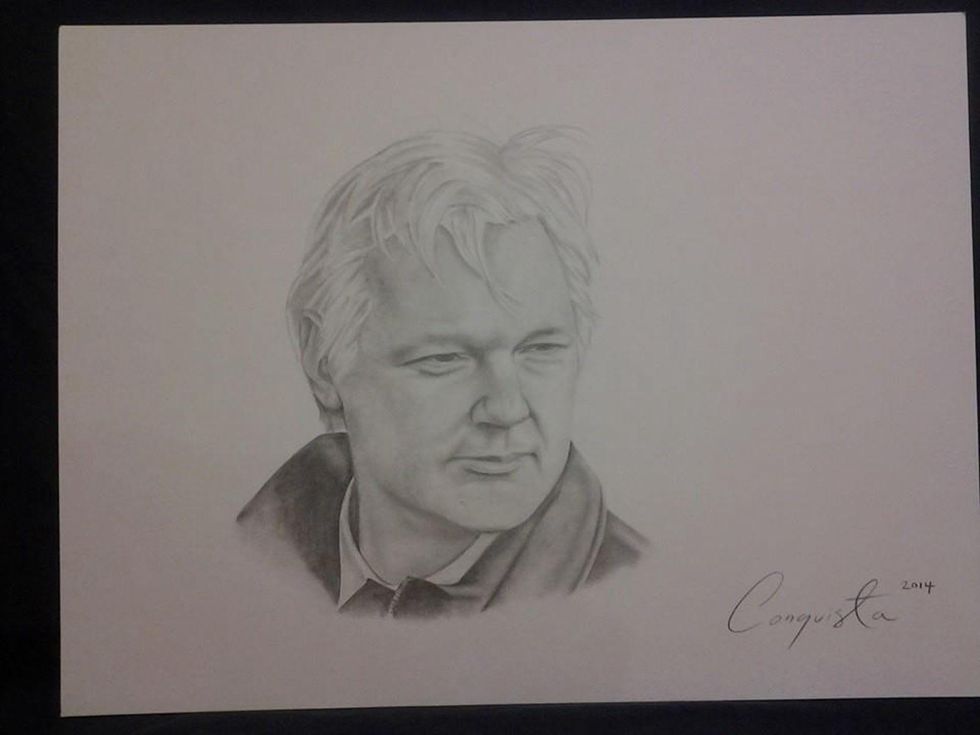

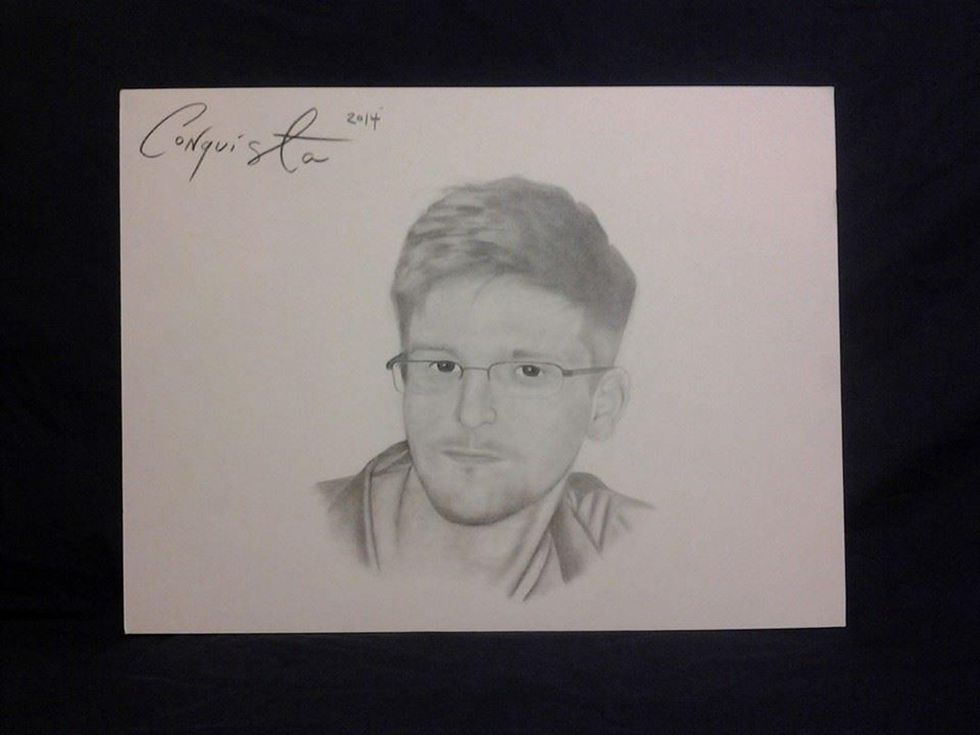

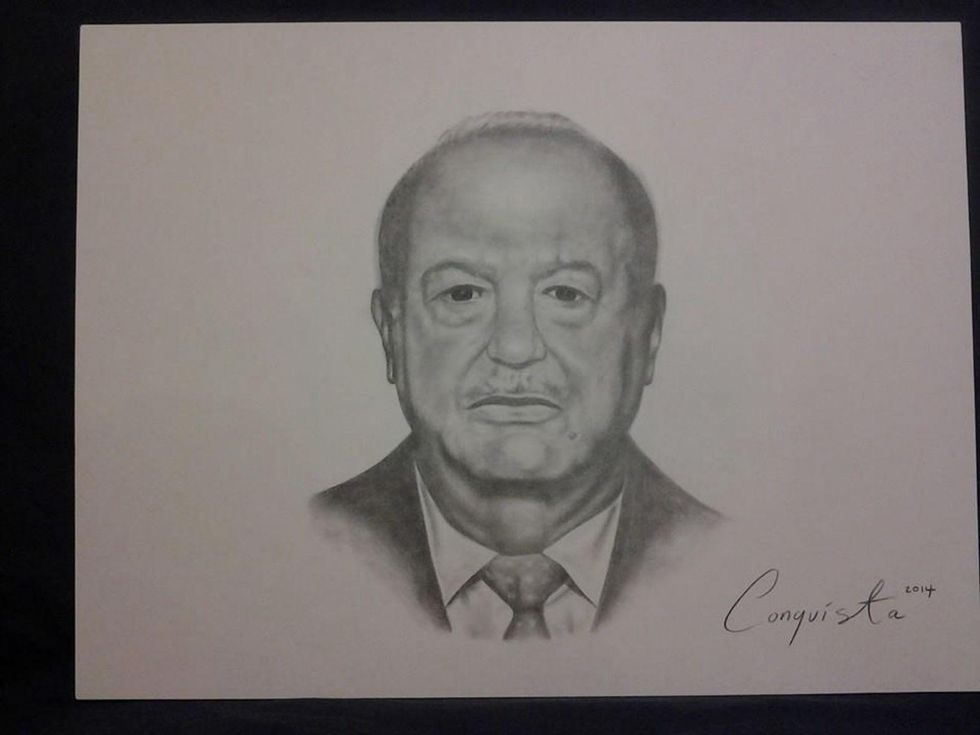

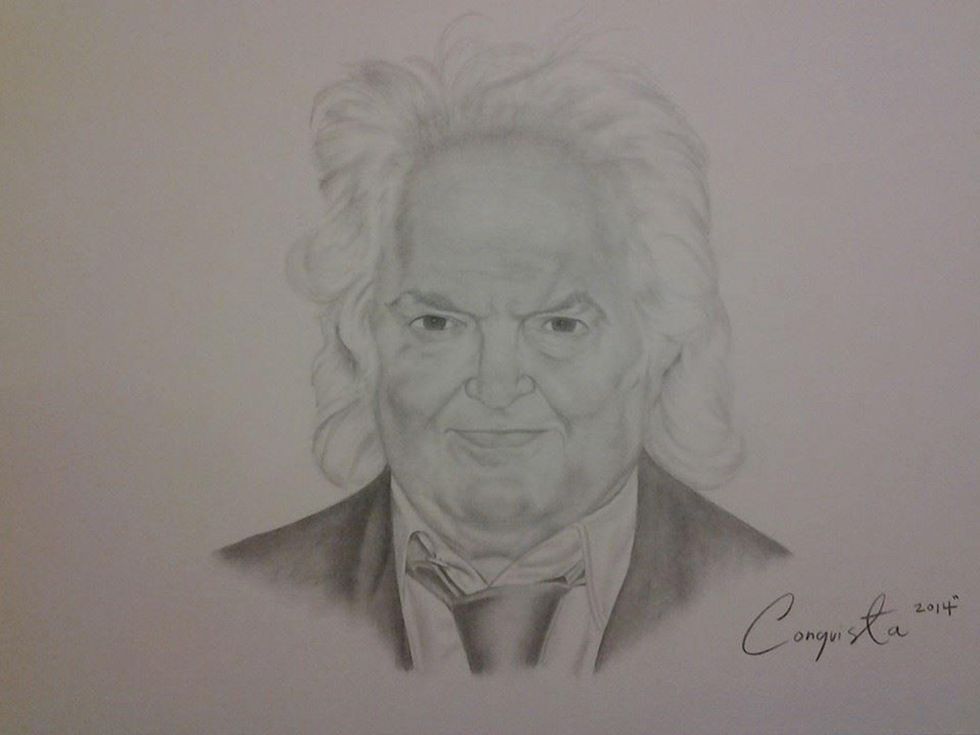

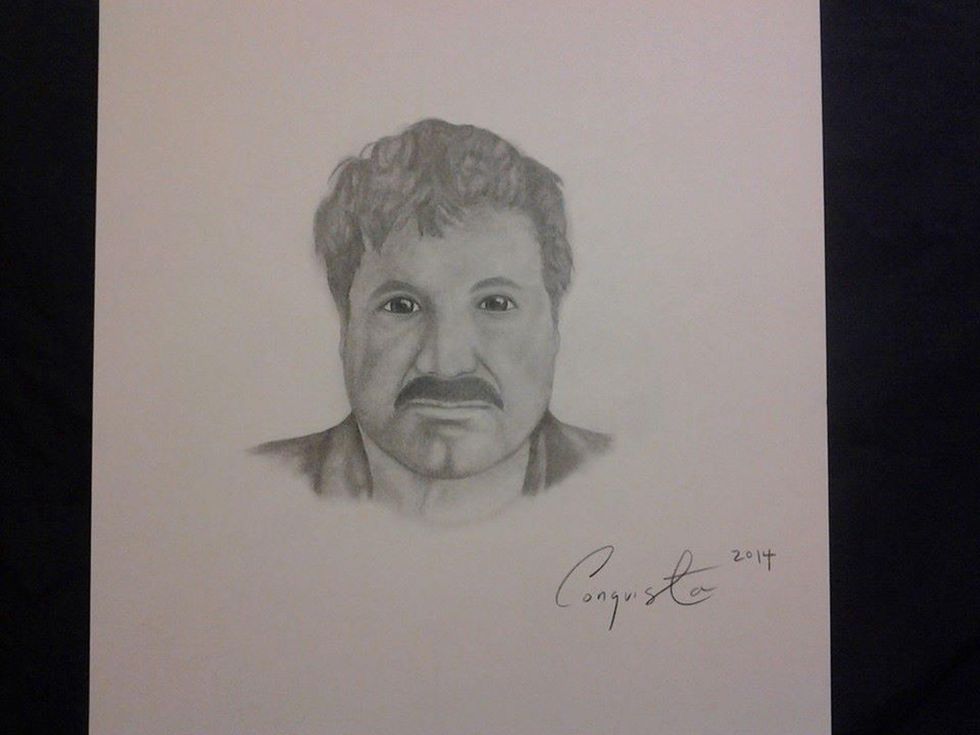

Thanks to regular TV coverage, Landeros says he enjoyed a bit of notoriety among his fellow inmates, allowing him to trade drawings for contraband books and art supplies. Along the way, he sketched a series of portraits that includes likenesses of Edward Snowden and Julian Assange, both of whom he cites as inspiration.

Out on parole, Landeros says he’s busy painting a new body of work while taking time to reconnect with family.

“My mother’s been a huge influence in my life, an activist and a true pacifist . . . You miss a lot of simple things in prison, but I think I missed family the most.”

In the coming weeks, Landeros will take on his largest art project to date — completing an unfinished mural at his parent’s Catholic church.

“It’s religious art, so it’s totally different from what I normally make. It’s cool though, something to do just for the community.”

Out on parole after nearly two years in prison, Picasso tagger Uriel Landeros stands by his 2012 Menil stencil attack at The Menil Collection.