The Review Is In

Solid Gold: Dazzling Das Rheingold elevates Houston Grand Opera to new heights

I suppose I’ve been waiting all my life for the La Fura dels Baus production of Wagner’s Das Rheingold. And while my many columns and opera reviews might have given readers the notion that I am always grasping desperately at the past, with Houston Grand Opera’s realization of Wagner’s masterpiece, I can look only to the future. This is, without doubt, the epitome of early 21st century opera production. It’s where we are going, and it’s thrilling.

Houston Grand Opera enters a new phase of its illustrious history with this stunning Rheingold, the first series of performances of the La Fura dels Baus production offered outside Europe. Conductor Patrick Summers creates a milestone in his impressive career, the singers advance artistically, and the city further establishes itself as a sophisticated, international center for opera.

This is, without doubt, the epitome of early 21st century opera production. It’s where we are going, and it’s thrilling.

My relationship to Wagner’s music begins in childhood, with my mother’s tales of my father, a brooding depressive, isolating himself and playing 78 rpm recordings of the “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde over and over. It was difficult in my early life, therefore, not to approach Wagner’s oeuvre without a bit of trepidation. This was dangerous music. I feared it might cast some sort of spell over me, too.

By my teenage years, I forged ahead and mail-ordered a gargantuan boxed set of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s 1953 live recording of the entire Der Ring des Nibelungen. Packaged without even a libretto, I listened to these records more as a kind of texture, without having any idea of the narrative, textual, or mythic complexities. The overture to Das Rheingold and the conclusion of Götterdämmerung, in particular, really drew me in, not to mention the famous “ride of the Valkyries” and Siegfried’s incredible funeral music.

It's complicated

The La Fura dels Baus production brings the first of these Ring operas, actually the “prologue” to the other three, into an extraordinary light, literally and figuratively. Historians, cover your eyes. I prefer to think of Wagner as classic, romantic, and contemporary (he foresaw the dissolution of tonality) all at once. His libretto is mostly overwrought, but it is also funny. When the three lovely Rhine maidens scoff at Alberich’s advances, for example, he offers them an alternative: “…Have your way then, with eels, if my skin is so foul!”

Wagner’s original score (at least as printed in the 1985 Dover facsimile edition) includes complicated stage directions that must have been challenging to realize in 19th century Europe. When the gold is first revealed in the first scene, Wagner instructs, “An increasingly bright glow penetrates the flood waters from above, flaring up as it strikes a point high up on the central rock and gradually becoming a blinding and brightly beaming gleam of gold; a magical golden light streams through the water from this point.”

It seems that the La Fura dels Baus team took these directions quite literally. In this particular scene, the Rhine maidens float in large glass fish tanks. The water is speckled with gold. The women descend into the water, Alberich is overcome, and the bright lighting cues exactly at the musical indication in the score.

At the same time, the production team has made Wagner fun, grand, and wildly symbolic, and always other-worldly.

At the same time, the production team has made Wagner fun, grand, and wildly symbolic, and always other-worldly. This is as it should be. I couldn’t help but recognize the irony of seeing Loge (so wonderfully portrayed by Czech tenor Stefan Margita) sail around the stage on a Segway two-wheeler. After all, a Segway tour company operates on the plaza right in front of the Wortham Theater, and I had just watched tourists finishing a run while I had dinner with friends across the street. It’s only one example of how current imagery punctuates this highly theatrical interpretation.

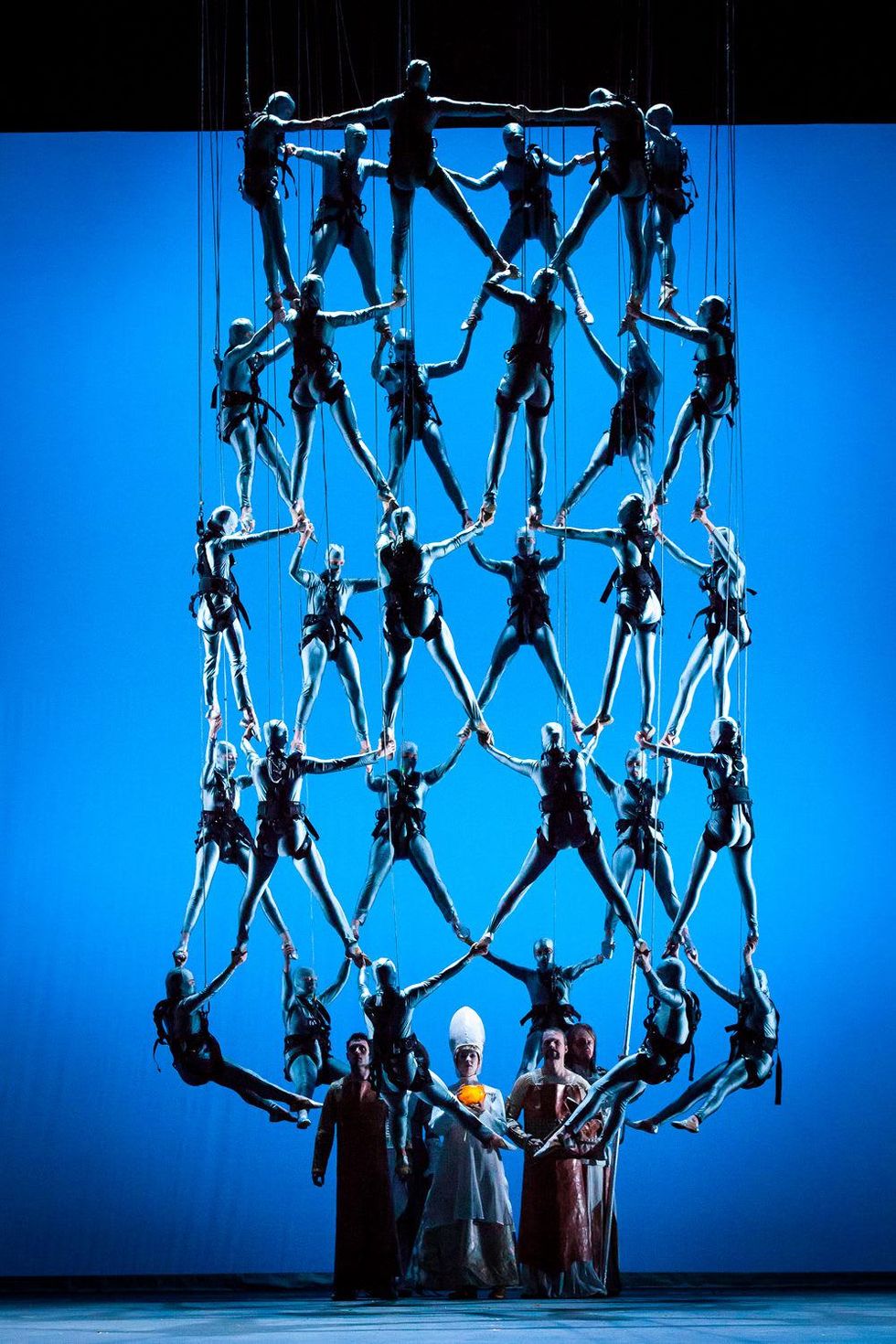

Cuteness aside, the sheer work involved in this production is dazzling. What metaphorical ideas emerge? For one, that the follies of the gods are measured in terms of human life. When Wotan and Loge descend into Nibelheim, the gold is being forged in a production line. The unit is a human body.

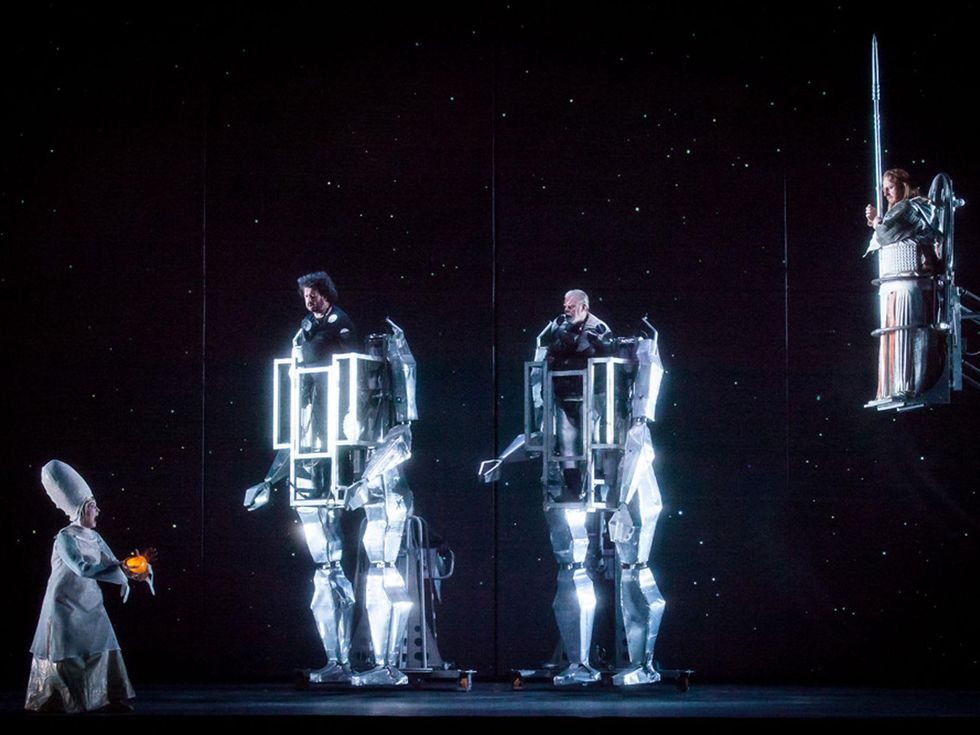

When the gates of Valhalla open at the conclusion, the doors are formed by human bodies. The gods rest at the helm of large cranes, the giants Fafner and Fasolt are towering metal monsters. Pardon the cliché, but really, you have to see all of this to really believe it.

One blemish

This is the first time I report that all of the singing in a Houston Grand Opera production was unconditionally stellar, from Iain Paterson’s booming, powerful company debut as Wotan, to Meredith Arwady’s mesmerizing and prophetic portrayal of Erda (fans will remember her as Auntie in HGO’s Peter Grimes). Jamie Barton gives a definitive, strong and passionate performance as Fricka, a role that puts her clearly in the upper echelon of great singers.

Icelandic bass Kristinn Sigmundsson is an archetypal Fasolt. Chad Shelton, who made such a classy appearance as Fredrik Egerman in HGO’s recent A Little Night Music, appears here as Froh, reveling in the tenor glory of this short but challenging part. This is likely the best all-around international cast I have ever heard in any Wagner opera.

Was there but a blemish in the opening night performance? I am sorry to say it was in the brass section, where more than a cracked, sour note or two emerged. I was quite disappointed, for example, when the first trumpet announced the appearance of the gold with a slur and then a decidedly flat high G. It’s little more than a C major arpeggio, yet this important leitmotif was ruined.

Iain Paterson as Wotan, from left, Meredith Arwady as Erda, Andrea Silverstrelli as Fafner, Stefan Margita as Loge, Kristinn Sigmundsson as Fasolt in Houston Grand Opera's production of Das Rheingold.