Book Talk

Domestic violence fuels new Houston author's inventive historical novel

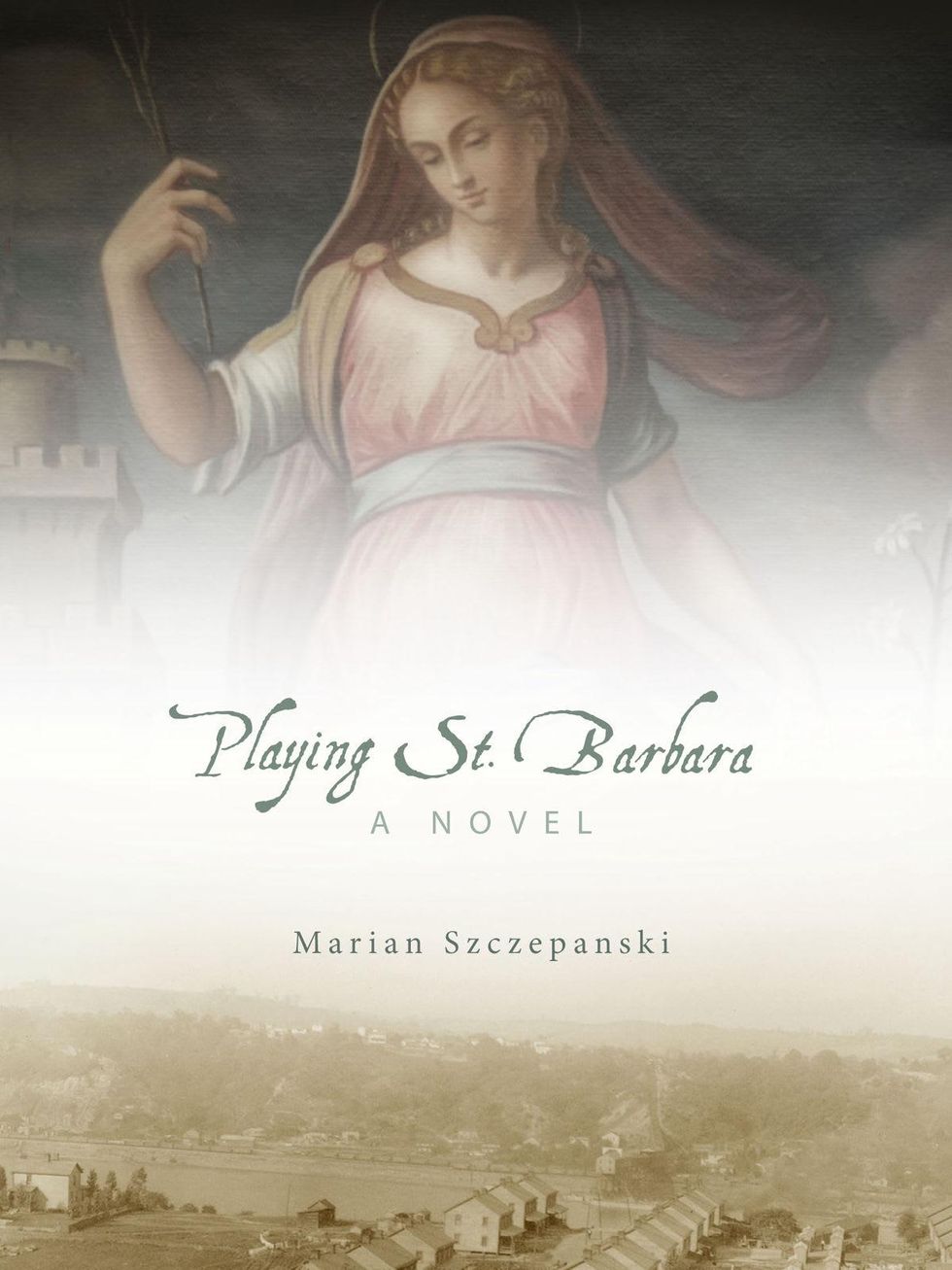

Sometimes the story of how a work of art came into being can be almost — though not quite — as fascinating as the piece itself. This is the case of Playing St. Barbara, the debut novel by Houston fiction writer and journalist Marian Szczepanski.

Working as as a volunteer domestic violence/information and referral hotline advocate at the Houston Area Women’s Center, Szczepanski soon learned that violence in the home does not discriminate. She spoke to very different women from all “walks of life,” yet they were all telling similar stories, and this was a story Szczepanski yearned to retell. Though she knew these tragic stories she was hearing should and deserved to be heard by a wider audience, she fought that impulse to pour them into fiction.

Speaking to me by phone a day before the official Playing St. Barbara book launch at Blue Willow Bookshop, Szczepanski confessed, “I really wanted to write about a woman in that situation, but something stopped me because I didn’t want to, in any way, breach anyone’s confidence. To write a contemporary story about it seemed to just be hitting to close to the bone.”

"This is a way for me to explore the issue of a battered woman, but I will be doing it in a different time and place.”

During this time, Szczepanski happened upon some advice in Poets & Writers Magazine to write what only you can write and it will find a home. She began to think back to her childhood in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The granddaughter of Irish and Slovakian immigrants, both her grandfathers, who died before her birth, were coal miners. She began to wonder about their lives and even more about the lives of her grandmothers about which she knew almost nothing.

“I was always interested in the women’s lives, she explained. “I heard a lot about the men and the dangers [in the mines] . . . but I didn’t hear a lot about what it was like to be a woman living there.”

It was at this point that her present experiences as a listener and advocate for the victims of domestic violence and her desire to gain more knowledge about her family’s past came together. And this is when Clare Sweeney, a coal miner’s wife and the mother of three daughters, was created on the pages of Playing St. Barbara.

“I thought maybe this is a story only I can write, and so when I thought of my main character I thought maybe this is a way for me to explore the issue of a battered woman, but I will be doing it in a different time and place.”

Forgotten Voices

Spanning the years between 1929 and 1941, the novel is divided into four sections with each section concentrating on Clare and one of her daughters. They all suffer under the violent hands of Clare’s husband and the girls’ father, Finbar. In another time and place, Finbar might have been a good man but alcohol and the mining company, which controls much of its workers’ lives, robs Finbar of his last strands of self-respect. He takes out his frustration and feelings of impotence on the women in his life.

Szczepanski set the novel during two decades that many readers will probably feel they know much about. Prohibition, FDR and the New Deal, the months before the U.S entered World War II, are histories recounted many times in nonfiction, fiction, and popular culture, but Szczepanski has found a place in this era that very few readers will know.

He takes out his frustration and feelings of impotence on the women in his life.

She went back to Pennsylvania to do research and discovered though there was documentation on the mines and the multicultural communities that sprang up around them, the women’s stories had been almost completely lost in time. One place she was able to find details about these lost lives was in the records of the mine companies’ private police force which used some “very heavy handed tactics” to break up any union activity and keep miners in line, but they also broke up domestic disputes.

This is when Szczepanski realized: “Domestic violence was not an issue I would have to make up.”

“So here was my story. I thought, I never got to talk to my grandmothers about it [their lives], but I will probably get to find out what their lives were like by researching and writing the book,” she explained.

Past and Present

I asked Szczepanski if she thought of the contemporary women calling into the HAWC hotline as she spent years researching and created these fictional miners’ wives and daughters. She answered the question by going back to Clare.

“She really believes that he might kill her or one of her daughters in a drunken fit or even if he gets angry enough. That was something I heard off and on: ‘I tried to run away but then I came back.’ There was always this absolutely overwhelming fear that there would be reprisals either to the woman herself or her children,” she said.

These issues and the women’s belief that they had to keep the family together, stayed with Szczepanski the whole time she was writing the novel. Yet, she also knew she had to give both her characters and readers hope. In Playing St. Barbara there is light at the end for Clare and each of her daughters.

They are “the little people” caught up in the “sweep of history,” but Szczepanski brings their fictional voices to a larger audience. Perhaps in this way, Playing St. Barbara equally plays tribute to Szczepanski’s grandmothers and all the women who call a hotline looking for a little hope of their own.

Marian Szczepanski reads at Brazos Bookstore on Jan. 13.