Islamic Treasures in H-Town

Fighting fanatics with art: Kuwaiti princess shares Islamic treasures with Houston — and the world

Can art change minds and lives? If that art is shared with the world, perhaps it can.

This seems to be the belief and life goal of Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah, a Kuwaiti princess and director general and co-founder of the cultural organization, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah (DAI), which holds one of the world’s largest private collections of Islamic art, now on permanent loan to the State of Kuwait.

For the next year, Houston becomes a part of that sharing as the Museum of Fine Arts and DAI continue a momentous collaboration with the new exhibition Arts of Islamic Lands: Selections from The al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait.

“It has become our responsibility to show the world that this is not the Islam that we belong to."

It goes on view, if not alongside, very near two new galleries that highlight the museum's own collection of Islamic art.

I recently had the chance to speak with Sheikha Hussah, who was in town primarily for the opening of the exhibition. (She made sure to schedule a visit with her very good friend President George H. W. Bush while she was here.) The elegant Sheikha spoke softly, yet passionatly about how art, in general, can be a force to educate and bring people together and how she hopes these pieces from the al-Sabah Collection, specifically, may do their part in helping us come to a better understanding of the real Islam.

“What is happening in our world with the atrocities committed by these fanatics have destroyed the image of Islam in the West,” she conceded despairingly, but all the more resolute. “It has become our responsibility to show the world that this is not the Islam that we belong to. This is their interpretation and these are fanatics. They are criminals. And this is not the real Islam,” she declared.

The Beginnings of a Collection

Though the al-Sabah Collection holds over 20,000 pieces of art, some 250 of which are on view at the MFAH, Sheikha Hussah does not consider herself a scholar or even a collector. In the beginning she left the collecting to her husband, Sheikh Nasser Sabah al-Ahmed al-Sabah, who started with one 14th century enameled glass bottle. The Sheikha reminisced, rather fondly it appeared to me, that her husband would describe that bottle “as a man would describe a beautiful woman.”

This one work of art grew to a collection of hundreds over the years, and Sheikha Hussah described their private accumulation almost as if a fine layer of art spread across every surface of her home.

“I am neither scholar nor a collector,” she reaffirmed, “but I have been entrusted with the collection. I have taken this responsibility."

And so something had to change.

“We decided they were not to be housed in a private home, and they are not the subject of after dinner conversation. They ought to be treated respectfully and be put in a place where they could be studied, enjoyed and shared by people. We shouldn’t keep them for ourselves. That’s how the idea of the museum started.”

Ironically, but perhaps appropriately, she now talks of her relationship with the collection as if it were another one of her children.

“I am neither scholar nor a collector,” she reaffirmed, “but I have been entrusted with the collection. I have taken this responsibility. It’s like rearing a child. You take care of the child. You want to educate and you want people to appreciate what this offspring is contributing to the society.”

From time to time she has also seen fit to send that “offspring” out into the world to do good, but never to the extent of this MFAH exhibition.

Stories Told by Art

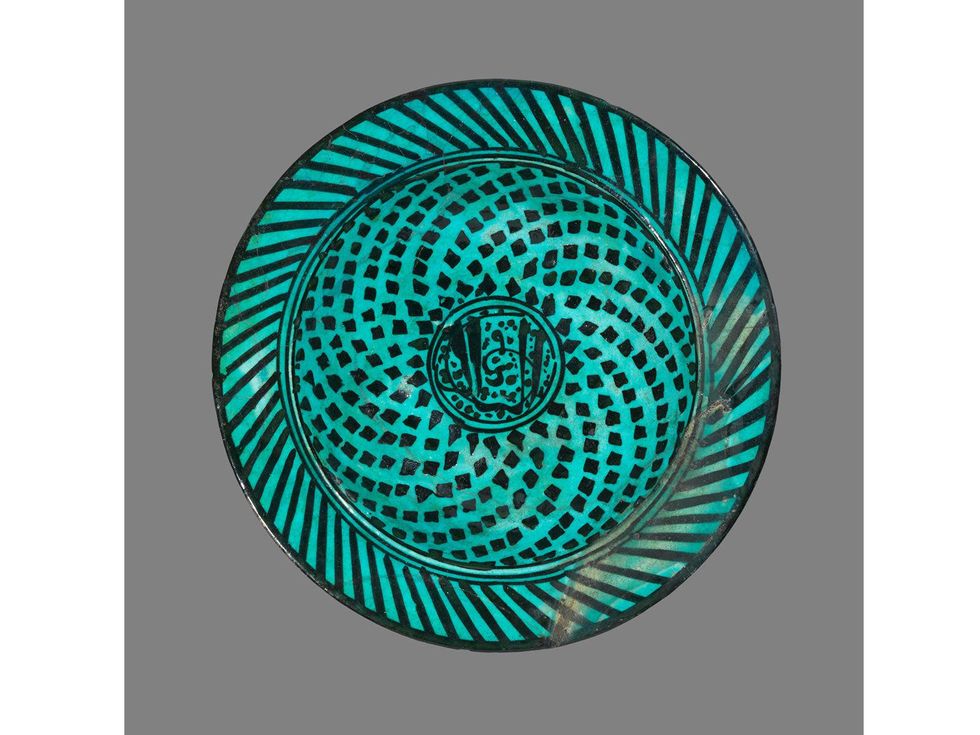

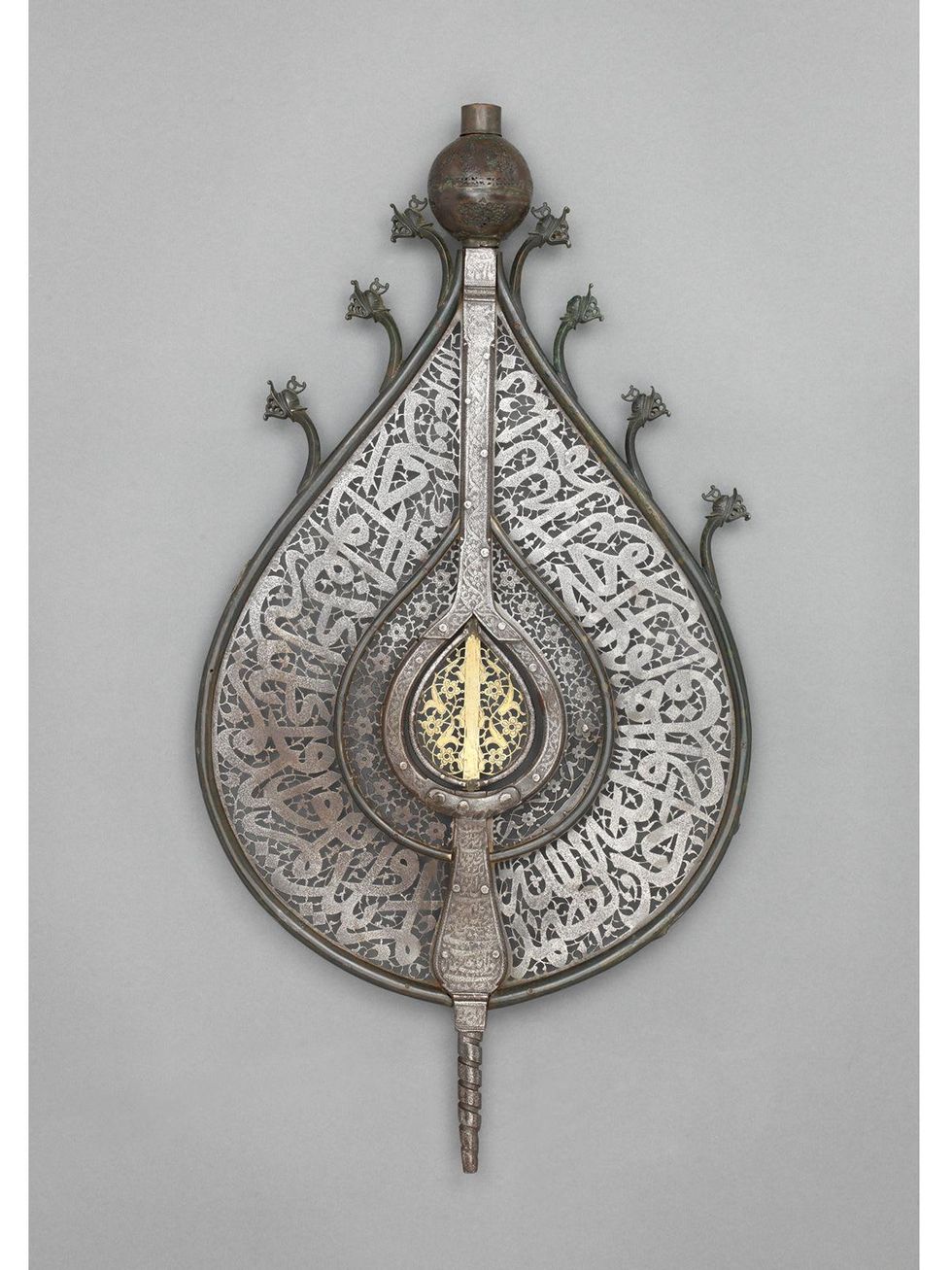

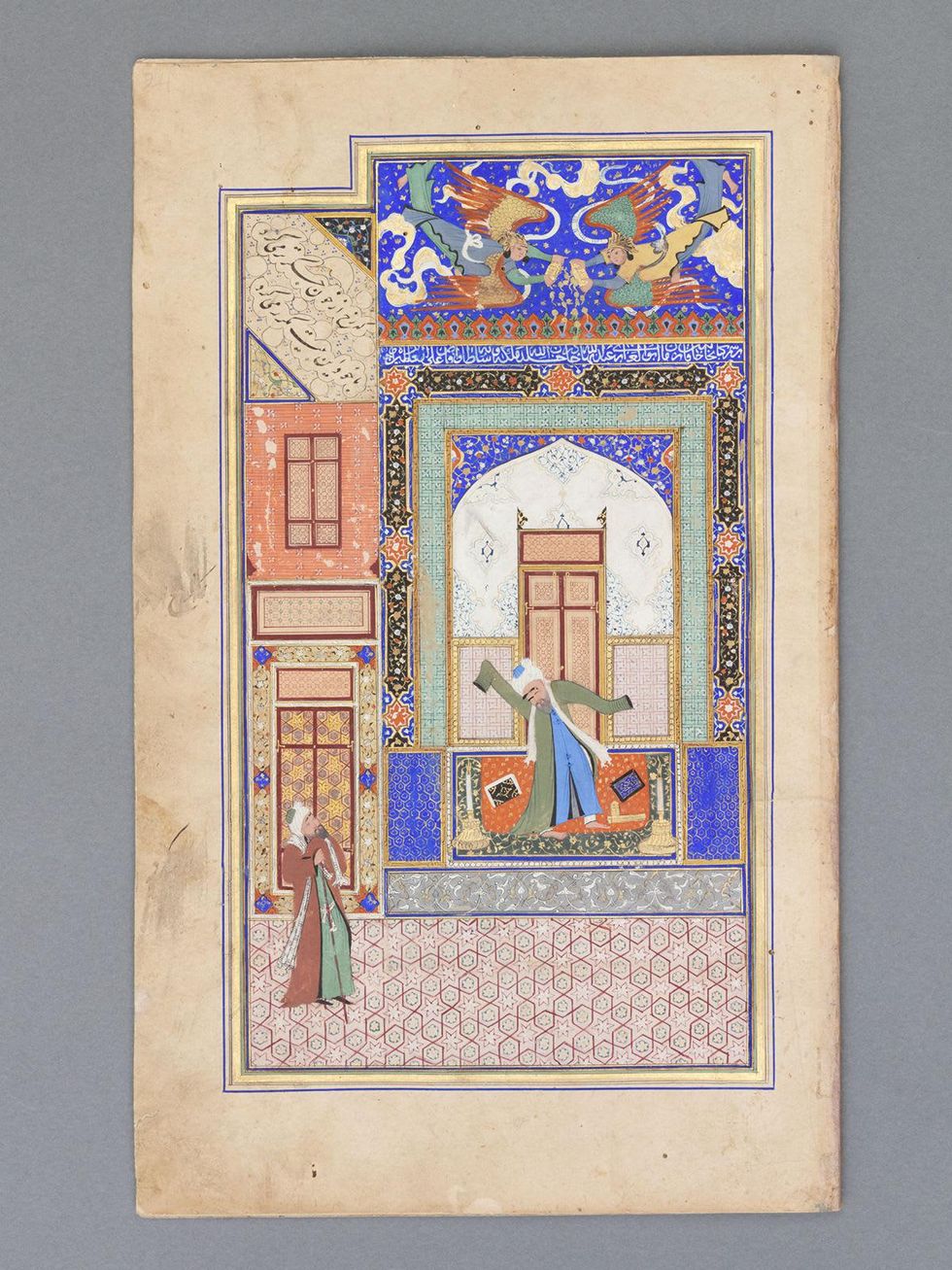

Arts of Islamic Lands spans from the 8th to 18th century and contains objects from the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, the Middle East, Turkey, India and Central Asia.

Though these pieces of metal work, textiles, jewelry and ceramics have sometimes been shown in other traveling exhibitions, the guest curator for Arts of Islamic Lands, Giovanni Curatola, told me during an early walk-through of the galleries that there has never been this comprehensive of an exhibition outside of Kuwait.

While each artwork held its own beauty, they also, individually and taken together, tell a story of a civilization and the single human lives that make up any civilization.

During our talk, Sheikha Hussah stressed the idea of art as an educator that has the power to spread enlightenment. I found I began to see what she meant looking at the pieces in the exhibition. While each artwork from an Egyptian Mosque Lamp to the Indian Bird Pendant, a chess set and even centuries old scientific instruments held its own beauty, they also, individually and taken together, tell a story of a civilization and the single human lives that make up any civilization.

“When objects are put together for the first time and juxtaposed to each other, suddenly new meaning emerges,” the Sheikha believes and included in her assessment the MFAH’s new dedicated Islamic Arts galleries, curated by Aimée E. Froom, the newly appointed curator of Arts of the Islamic World.

“There’s a conversation between objects that we didn’t know about,” Sheikha Hussah says. “If we allow ourselves to hear their voices they can tell us many stories, but we have to listen.”

And now until Jan. 30, 2016, Houstonians will have the chance to hear that remarkable millennial old conversation.