Book Review

Larry McMurtry is never afraid to write what's on his mind

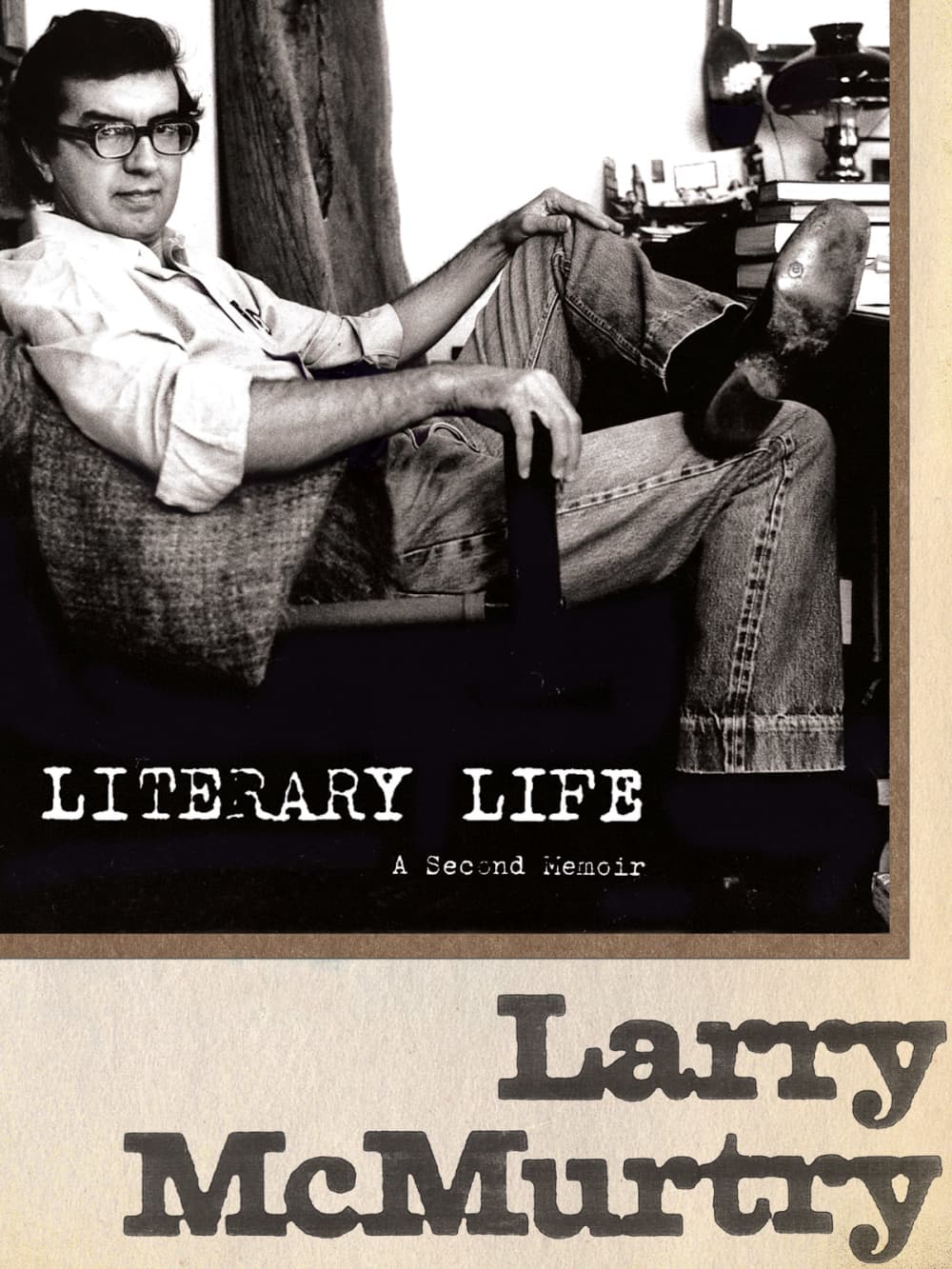

Photo by Diana Lynn Ossana

Photo by Diana Lynn Ossana

In Literary Life: A Second Memoir, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Larry McMurtry is surprisingly modest about his enormously successful life in letters. He calls himself “a minor writer . . . Little of my work in fiction is pedestrian, but, on the other hand, none of it is really great.”

Even so, he sounds occasionally bitter about what he calls “the lack of interest in my books” by the literary establishment. His work is rarely reviewed, he complains, and the reviews he gets aren’t interesting or intelligent.

Whatever his critics think, however, McMurtry’s fans love his novels, a dozen of which have been turned into such highly successful movies as Hud, The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment and Lonesome Dove.

McMurtry’s strong point is telling stories, and the “one gift” that led him to a career in fiction, he writes, is “the ability to make up characters that readers connect with."

As book editor of the defunct Houston Post, I found McMurtry to be one of the most interesting authors I ever read or interviewed. Born 73 years ago, he grew up in a house without books near Archer City, destined to be a cattleman like his father. Instead, he became not only a prize-winning novelist and screenwriter but also a dealer and owner of thousands of rare books.

His first memoir, Books, published in 2008, covered his career as a bookseller; his next and final one, according to his publisher, will concentrate on his Hollywood life, including winning an Academy Award for writing the screenplay, with Diana Ossana, for the film, Brokeback Mountain.

Houston, where McMurtry has lived off and on for 17 years, figures prominently in Literary Life. He first lived here as a Rice student, returned later to teach at the private university, and once owned an antiquarian bookstore in the Heights. He has also lived for brief periods in several other Texas cities, including Fort Worth and Austin, but calls Houston “by any measure the most interesting city” in the state.

The outspoken and sometimes prickly McMurtry, however, has nothing but contempt for Archer City, where he lives and works part of each year.

“Simply put, it’s not a nice town,” he writes. The locals are “indifferent” to students in the frequent writing seminars held in the tiny West Texas town, and equally indifferent to his massive bookshop operation there – four large buildings filled with books.

McMurtry is equally critical of The Texas Institute of Letters, an organization whose members include many of the state’s best-known writers. They spend their time “making virtuous pronouncements,” he charges, and “the rest of the time congratulating themselves for obscure feats of one sort or another.”

There’s lots more of interest here for McMurtry fans, including as much about the books he’s read and been influenced by as about his own work, and his association and assessment of writers ranging from Norman Mailer, Salmon Rushdie and John Updike to fellow Texas author John Graves (“every sentence he’s written is readable”). He also expresses humorous opinions on topics ranging from writers’ conferences (“lots of drinking and as much infidelity as the participants can squeeze in”) to fortune tellers (he’s been to “probably fifty . . . in many cities and several countries”).

McMurtry has never had “writers’ block,” he notes, and still, at age 73, writes five pages a day. The result is some 40 books and numerous screenplays, all of which have been completed while working fulltime as a bookseller.

Some of those books were produced at lightning speed. He churned out The Last Picture Show, about life in a small Texas town in the 1950s, “in about three weeks.” He wrote All My Friends are Going to be Strangers (set in and around Houston) in five weeks and The Desert Rose in an astonishing 22 days.

Literary Life must have also been churned out quickly, and critics will find plenty to complain about. McMurtry repeats a lot of material he covered in his last memoir, Books, and several chapters end abruptly, leaving the reader wondering what happened. He also has a habit of saying “I believe” or “I can’t recall” on matters he should have looked up, and although memoirs usually reveal a lot about the author’s personal life, McMurtry tells us precious little about his.

Despite such complaints, his fans, including me, will be looking forward to his third memoir. Yes, he’s lazy and takes a lot of short cuts. But as Publishers Weekly concluded in its review: “McMurtry’s understated style is charming and deceptively sophisticated” — and he’s such an entertaining writer.