Houston could use an artful respite this month. Luckily most of our museums, galleries and public spaces have reopened their doors to give us some peaceful, chilled moments to contemplate a little beauty. From intangible laser sculptures to outdoor soundscapes to portraits that tell stories of survival, to cool summer Saturday nights at the MFAH, there’s a lot of art variety in Houston this month and opportunities for a much deserved art break.

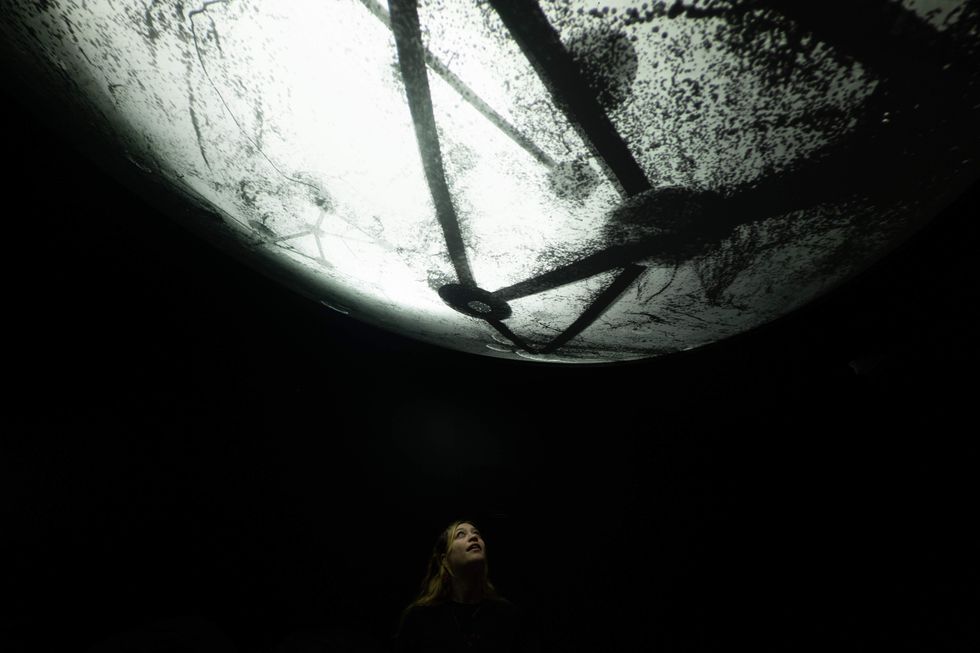

“Time and Space” at Artechouse (ongoing)

The inaugural presentation of exhibitions at Houston’s newest immersive art space, Artechouse, consists of three separate art shows that touch on themes of time and space, from a cosmic to subatomic level. “Beyond the Light,” an Artechouse Studio creation made in collaboration with NASA, translates real NASA data and technology into multimedia exhibits and installations, including an immersive cinematic room using some of the latest images from the James Webb Space and Hubble Space Telescopes. “Intangible Forms” is a survey of work from award-winning Japanese multimedia artist Shohei Fujimoto who uses choreographed lasers, strobes, and moving lights to play with our understanding of reality and light. Making its U.S. debut, the third exhibit “Eternal Life” was originally commissioned by the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm and uses Nobel Prize winning scientific and literary works as inspiration for an abstract, immersive light and video installation.

“Art in the Park” at Hermann Park (ongoing)

If it’s been a while since you’ve taken an art walk in Hermann Park, you might be surprised by what’s in bloom this summer. The Play Your Park, a $55.5 million capital campaign aimed at improving and maintaining Hermann Park, has planted the seeds of a dramatic new vision for Hermann Park. The Commons, the park’s recently opened new play gardens, elevates the traditional park playground into a new art form.

But the Play Your Park campaign has also renewed their public art initiative with two, new, large-scale art installations. With the Commons opening, the park has unveiled, “Scattering Surface,” a 16-foot high sculpture, composed of thousands of welded stainless steel circles, which reflect light and scatter the visible surroundings into tiny pieces. And this month brings the installation of “Canopy,” by Anthony Suber, a Houstonian and UH professor. The artist designed the enormous metal and glass structure in the form of an enlarged, abstract monstera plant to represent enlightenment and spiritual harmony.

“Prints & Drawings: Selections from the MFAH Collection” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (now through September 1)

The MFAH’s collection is so vast it can’t all be on view at any one time. This special, temporary presentation of 60 works gives us a chance to see the breadth, depth, and diversity of their print and drawing collection. The exhibition contains a variety of works rarely seen together, including drawings by Hungarian Jewish artist Ilka Gedő, prints by conceptual artist Carroll Dunham, and a selection of print and drawing self-portraits of artists and prints from the influential New York printmaking studio Universal Limited Art Editions.

“Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (now through September 15)

Art many times reflects the times in which it was created and can become a revealing chronicler of history. Case in point, this monumental exhibition at the MFAH gives visitors an insightful view into the enormous cultural and technological changes within Japan during the Meiji era (1868-1912). Featuring over 150 objects including paintings, prints, photographs, and sculpture, as well as superb examples of turn of the century enamel, lacquer, embroidery, and textiles, Meiji Modern tells the story of Japan’s cultural transition from almost 200 years of near total isolation into a distinct presence in global society. The exhibition also features several recently discovered masterpieces of Japanese art, many of which have never been shown publicly.

“Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan provides a fascinating window onto this transformative era, a collision of culture and identity that forged newly modern approaches to esthetics, trade, and statehood in Japan,” MFAH director Gary Tinterow said in a statement. “It also shows to great effect the unprecedented achievements of Japanese artisans and artists, culminating centuries of technical perfection.“

“The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (now through September 2025)

This 36-channel immersive video installation by influential painter, photographer, and Pop artist, David Hockney, was first seen as a part of the MFAH’s 2021 exhibition, “Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature,” and now joins the museum’s permanent collection. Even when introduced to museum-goers amidst the vibrant Van Gogh artwork, it called viewers to stop, sit, and contemplate time, nature, and the human subjective perception of them both. Hockney chronicled the change of seasons over a year along the same wooded road in Yorkshire, England, using nine cameras at different angles and exposures to film an afternoon in the same place during spring, summer, fall, and winter. Look for the installation in the Nancy and Rich Kinder Building, joining some of our other world-renowned immersive large-scale works like Kusuama’s “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity.”

“Phillip Pyle II: So Far So Good” at Houston Museum of African American Heritage Heritage (July 12-September 14)

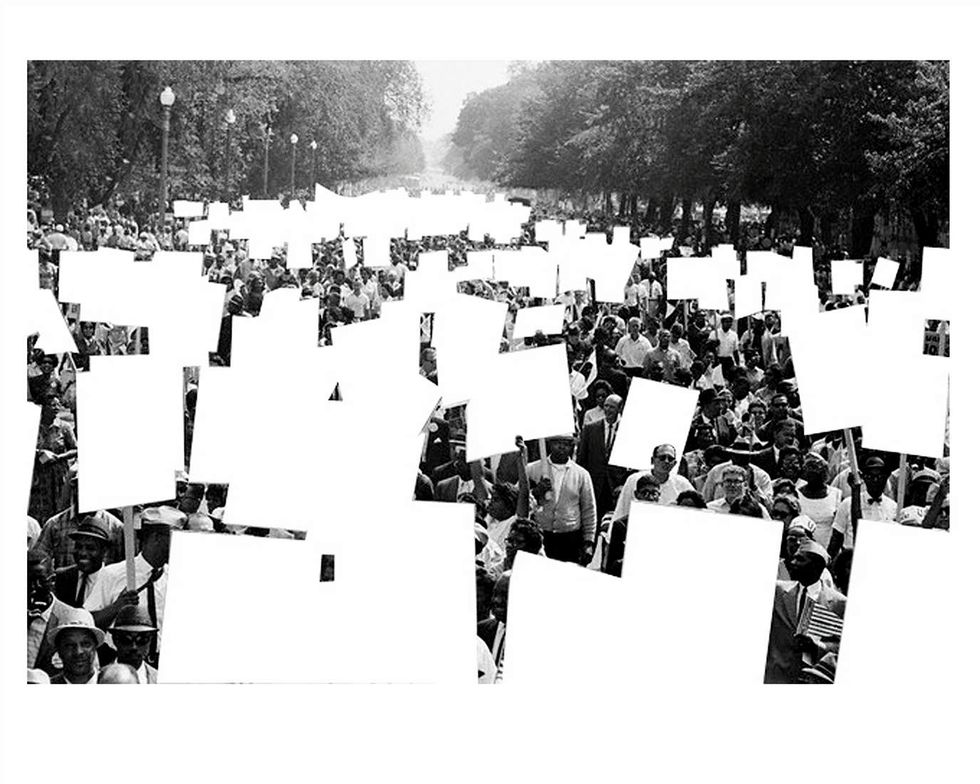

In this survey of the Houston visual artist, photographer, and “agitator” HMAAH figuratively turns over “the keys of the museum” to Pyle to better reveal the design, humor, and craft of his work. These pieces meld together images from mass media and advertising to create complex visions with a comic touch that also questions cultural values and beliefs.

“By blending photography, digital art, and performance, Pyle creates visually arresting pieces that challenge perception and the history we have been told,” HMAAC chief curator Christopher Blay said. “His works often juxtapose historical and contemporary elements, creating a dialogue between the past and the present.”

“The Talking Back of Miss Valentine Jones” at Houston Museum of African American Heritage (July 12-September 14)

Each year, HMAAC awards the works of an emerging Houston-based artist with the Bert Long Jr. Prize. This exhibition showcases this year’s winner, Shavon Aja Morris, who repurposes found imagery into photographic collages to offer a renewed encounter with images of Black American woman. For this show, Morris has gathered images from vintage issues of Ebony Magazine to create collage works that explore themes of resilience and theories of genetic memory, the idea that environmental memories can persist in genetics for 14 generations.

"Facing Survival | David Kassan" at Holocaust Museum Houston (July 12, 2024-January 25, 2025)

Acclaimed for his paintings that balance a naturalistic depiction of faces with abstract backgrounds, David Kassan’s portraits tell complex tales. For this extraordinary exhibition, Kassan uses his art to tell the individual stories of more than 24 Holocaust survivors. Before beginning each portrait, Kassan engaged with each survivor, filming their testimonies and learning of their lives, strength, and fortitude. The accompanying preparatory sketches he makes for each painting also tell the tale of that artistic journey getting to understand each subject.

A highlight of the exhibition for her fellow Houstonians will likely be the portrait of Ruth Steinfeld, whose parents released her and her sister to the care of the French Jewish humanitarian organization OEuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) to save their lives. After spending the remainder of the war in French orphanages and with a foster family, their grandfather brought them to the United States in 1946. Steinfeld’s portrait includes her displaying the French Legion of Honor medal. This highest honor in France was bestowed upon Steinfeld for her continued role in teaching young people about the Holocaust.

“Invisible Music” at City Place (July 20-September 15)

As part of their initiative to to weave artistic, experiential elements into the everyday fabric of this North Houston development, City Place has commissioned Austin-based artist/musician Steve Parker to create a new experiential musical journey for visitors. Parker uses repurposed brass instruments to create musical sculptures that will become a symphonic meditation on nature. Consisting of sound-trumpeting assemblages perched on floating platforms within the “cat eye” reservoir of the park’s main pond, these musical sculptures create a soundscape adapted from French composer Eric Satie’s “Furniture Music” and set against a backdrop of nature sounds, including insects, birds, and bats. Along with the floating pieces, interactive sculptures placed along the greenspace surrounding the pond will allow participants to alter the soundscape’s overall musical composition.