The Arthropologist

Blood, sweat & sacrifice: In the world of dance, practice really does makeperfect

Hitomi Takeda in a Houston Ballet company class led by Steven Woodgate (notpictured)Photo by Greg Lacoste

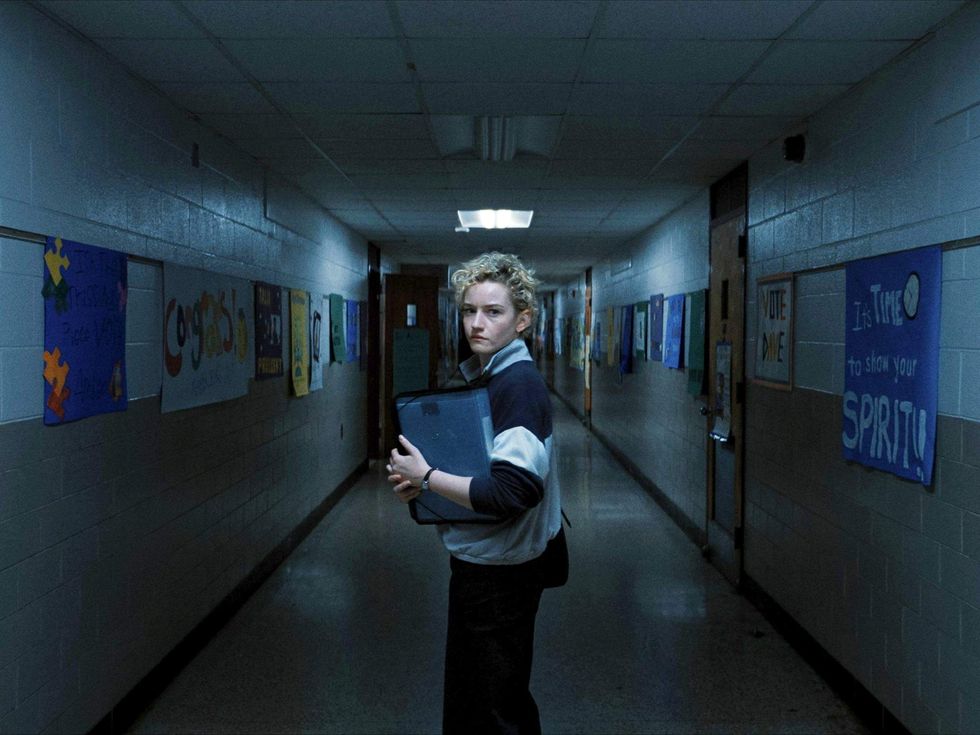

Hitomi Takeda in a Houston Ballet company class led by Steven Woodgate (notpictured)Photo by Greg Lacoste Amy Ell of Vault in "Torn"Photo by Lynn Lane

Amy Ell of Vault in "Torn"Photo by Lynn Lane Morning Company class (open to the public) for Hope Stone Dance every Wednesdayand Friday mornings is part of the morning ritual for dancers.Photo by Simon Gentry

Morning Company class (open to the public) for Hope Stone Dance every Wednesdayand Friday mornings is part of the morning ritual for dancers.Photo by Simon Gentry Modern dance class at University of Houston's School of Theatre & DancePhoto by Jackie Nalett

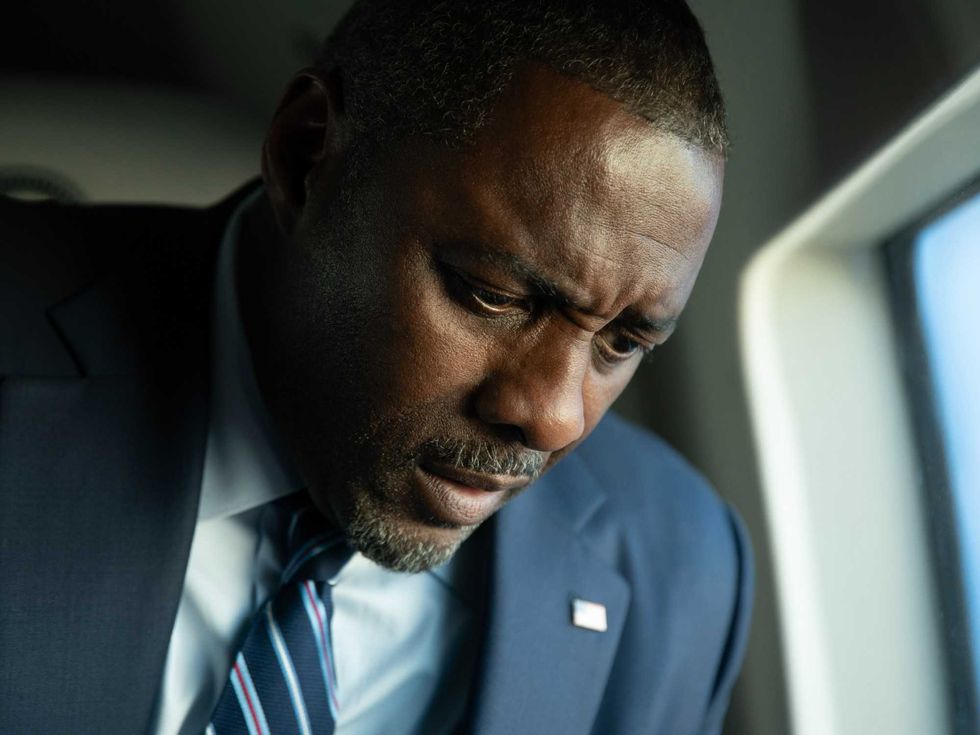

Modern dance class at University of Houston's School of Theatre & DancePhoto by Jackie Nalett Daniel Russell showing off his technique in "Billy Elliot"Photo by Kyle Froman

Daniel Russell showing off his technique in "Billy Elliot"Photo by Kyle Froman Vault members Joani Trevino and Alicia McGee in Amy Ell's "Torn"Photo by Lynn Lane

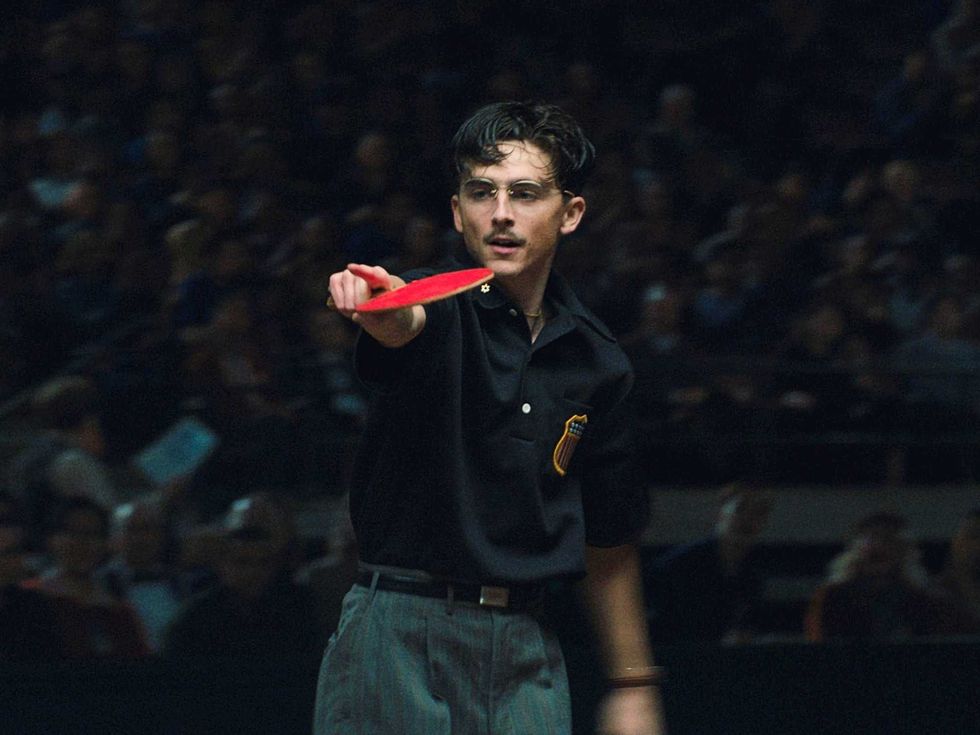

Vault members Joani Trevino and Alicia McGee in Amy Ell's "Torn"Photo by Lynn Lane In Cirque du Soleil’s "OVO," a spider (LI Wei) defies gravity, including anupside-down unicycle act. LI is one of the only artists in the world to performthis act.Photo by Benoît Fontaine © 2009 Cirque du Soleil

In Cirque du Soleil’s "OVO," a spider (LI Wei) defies gravity, including anupside-down unicycle act. LI is one of the only artists in the world to performthis act.Photo by Benoît Fontaine © 2009 Cirque du Soleil From left, Jacqui Grady, Zach Bruton, Rachael Logue, Jamie Geiger and Kim Tobinat Kim Tobin Acting Class at Stages Repertory TheatrePhoto by Jamie Geiger

From left, Jacqui Grady, Zach Bruton, Rachael Logue, Jamie Geiger and Kim Tobinat Kim Tobin Acting Class at Stages Repertory TheatrePhoto by Jamie Geiger

"Why do dancers have to take class every day? Don't they have it down by now?" a man asked me after a lecture.

It was an honest and somewhat naive question, pointing to how little we understand training in the performing arts. Training is an astounding thing, and we recognize it when we see it.

There's a magical moment in Billy Elliot when he stuns his classmates with his balance and line. Even his miner dad eventually sees his power.

And didn't we all gasp at how ballerina-ish Natalie Portman looked after one year of training (well, at least her arms did, thanks to Kurt Froman's excellent ballet classes)? The bottom half of crazy girl Nina Sayer belonged to the uber technician Sarah Lane, an ABT soloist. Dance Magazine Chief Wendy Perron sets us straight on the training truth behind Black Swan blackoutgate.

We are talking blood, sweat, sacrifice, time and tears when it comes to performing artists' dedication. Most of us know that musicians clock in six hours a day; Performance Today has an excellent series detailing The Art of Practicing right now. But we are less familiar with the rigor it takes for other artists to complete those movement marvels night after night without a hitch.

When LI Wei runs back and forth on a swinging slackwire during his act as part of Cirque du Soleil's OVO , you bet it's taken years to manage the particular neuromuscular connections to make it all look second nature. LI is one of the few people in the world with the chops to pull it off.

Andrew Corbett, Artistic Assistant for OVO, knows a thing or two on the specificity of training when it comes to managing the cadre of human wonders at Cirque.

"In addition to full-out, daily performance, our artists train two hours a day on average," says Corbett. "Most Cirque performers were first high level, competitive athletes. Cirque teaches them to be artists as well. They train in dance, improvisation and character development for at least a year before joining a show."

Amy Ell, founder of Vault, Houston's leading aerial dance artist, took the opposite path, seeking out circus training to augment her contemporary work. When Ell hangs from the ceiling of Spring Street Studios in her newest piece, Torn, during Spacetaker's SOLD OUT gala this Saturday, there's a whole lot of smarts in both her movement and rigging choices.

Sure, she's fearless, but not without an immensely vast knowledge base keeping her suspended mid-air. Ell, widely known on the international aerial dance circuit, has studied with circus experts all over the globe and now conducts her own teacher training at Gyrotonic Houston, her second operation. Ell is also a Master Level One Gyrotonic Trainer, one of a handful in the world.

"I have to cross train for the upper body strength," she says.

Training is daily and specific to the art form. Without it, believe me, you can tell. I have sat through too many performances where daily class was the missing element. No, rehearsal is not enough.

So if you were one of the lucky ones dazzled by Joseph Walsh's last minute fill in for Connor Walsh on opening night at The Sleeping Beauty, know that those snazzy double cabrioles didn't come from playing video games, but morning ballet class, where a dancer works diligently on "getting it down."

For contemporary dancers, daily class has some serious obstacles, like the fact that most dancers have to work at day jobs, leaving only evenings to rehearse and train. Plus, after you graduate from college, you have to find a place to train. Karen Stokes, Head of the Dance Division at UH's School of Theatre & Dance and Artistic Director of Travesty Dance Group, copes with this situation often. Luckily, UH grads can continue training at UH for a small donation.

"If I could pay my company dancers a realistic living as dancers, they would be able to focus completely on their training and performing. But, I can't, and they have to figure out how to do both," says Stokes. "It's not a perfect world. The fact that they make this choice at all is a testament to their passion as dancers."

Stokes offers a warm-up or company class before each rehearsal. "It gets us all going as a company and it provides a regular technique routine."

Jane Weiner, founder of Hope Stone, came here from New York's competitive dance scene, where she had numerous choices for daily class. In Houston, the prospects are slim, which is why she founded Hope Center, one of the few places to take daily class for contemporary dancers.

"Class is also a time to come together as a community," says Weiner, who is also working with Houston Ballet II for her upcoming An Evening of Bread and Circus. "And it's a great way to introduce material from whatever dance I am working on."

In this case, Weiner used class time to immerse HB II in her vocabulary. Houston Ballet offers adult open classes and hopes to expand its offerings now that they have more space at Center for Dance.

Watching Courtney Jones teach Suchu Dance's company class, I was struck by the play of bold movements mixed with tiny details. These dancers need more than a ballet class to become fluent in Jennifer Wood's highly nuanced choreographic edges, and they have found a good match in Jones' eclectic approach. Jam packed with quirky gestures, loose energy and an animated physicality, Wood's idiosyncratic vocabulary takes time to master; the qualitative range, the quick shifts in direction and an organic sense of theatricality require the same amount of attention as 36 consecutive fouettes.

Suchu also performs excerpts of her newest opus Masters of Semblance at SOLD OUT. Her show runs March 24-April 3 at Barnevelder.

Actors train, too. Do you think complicated emotions just come out of nowhere? Had a dancer been used instead of an accomplished actor in Black Swan, I would be complaining about something else.

"Training for actors is not widely understood," says Kim Tobin, director of Kim Tobin Acting Studio, which is based in the Meisner and Adler approach. "You have to work out your emotional muscles. It's what makes any character believable." Just like dance, performing in a play is distinct from training.

"You need a place with a safety net to take risks and make mistakes," says Tobin, who is launching The Stark Naked Theatre Co. with Philip Lehl in May with Debt Collectors, a modern adaptation of August Strindberg's Creditors at Obsidian Art Space. "On the job you apply your skills."

For Tobin, post-theater school training is essential. "College provides a good foundation, but you need to continue to work on yourself."

So the next time you see a performing artist do something amazing, know that the second that it took to accomplish it actually took years to master.

Watch humans do an amazing job of pretending to be insects in Cirque du Soleil's OVO

Houston Ballet principal Sara Webb didn't hang around the mall when she was a teen to dance like this.