Travelin' Man

The hidden Inca ruins: This fortress adventure takes you far off the regular tourist paths

It was a strange twist. Suddenly we found ourselves at the center of attention, when a group of students, I assumed high school, rushed over to take pictures. They lined up — with us in the middle like trophies — and their classmates took turns hitting shutter buttons. I stood out as at least three heads taller in every picture.

Of course we played along, but were surprised by how much scrutiny we garnered, given the fact that we all were surrounded by carved stone friezes immense citadels, and nearly 400 structures, some dating back to the 7th century, pre-Incan in other words.

After posing for a handful of photos, I realized that we were probably the only tourists for miles and definitely the only ones among the few visitors. Nearly one million sightseers from all over the globe trek to the world-famous Inca ruins of Machu Picchu in southern Peru annually.

We were probably the only tourists for miles and definitely the only ones among the few visitors.

In contrast, the impressive fortress of Kuelap in the north sees less than 15,000 visitors.

The day we hiked up to the ruins, spending several hours traipsing about the huge bulwarks and remaining circular walls, we saw only a dozen other visitors in addition to the school group, all of them Peruvian. We definitely had left the well-trodden tourist track. The ruins perch at an airy location, overlooking vast valleys and endless mountains.

The extensive archeological site offers plenty of space for peaceful wandering and quiet solitude. Much of its history and culture remains unknown.

The area’s only sizeable city and main transport hub, Chachapoyas, lies two and a half hours by bus to the north. The city’s name stems from the ancient people and culture of the region, which in addition to Kuelap, left numerous ruins and burial sites scattered throughout the precipitous valleys of northern Peru. The Incas gave the name Chachapoyas, meaning warriors of the clouds, to the people who reigned throughout the mountains between the Marañón and Huallaga rivers.

The distinct civilization of the Chachapoyas flourished between the 8th and 15th century, until it was conquered by the expanding Inca Empire and completely lost after Spanish colonization. The area now lies within the southern part of the Amazonas region of Peru, a land of rugged peaks and deep canyons covered with humid tropical forest.

Getting There

By combination of bus and a rattling colectivo (small vans that ply the back roads), we managed to reach the small, dusty town of Nuevo Tingo. The old part of town had apparently been swept away by a flood and a new village was constructed atop a higher bank. From the village center, a few cobblestone streets ran arrow straight in cardinal directions, turning into dirt paths before coming to dead-ends in fallow fields. The main plaza, a tight square of gray stone, was surrounded by colorful, but faded houses.

A handful of villagers kept busy sweeping dust off storefronts and boardwalks, a seemingly futile task, as sandy gusts blew from the surrounding hills.

Massive walls of limestone slabs, reaching 60 feet high, stretched left and right for nearly 1,000 feet in length.

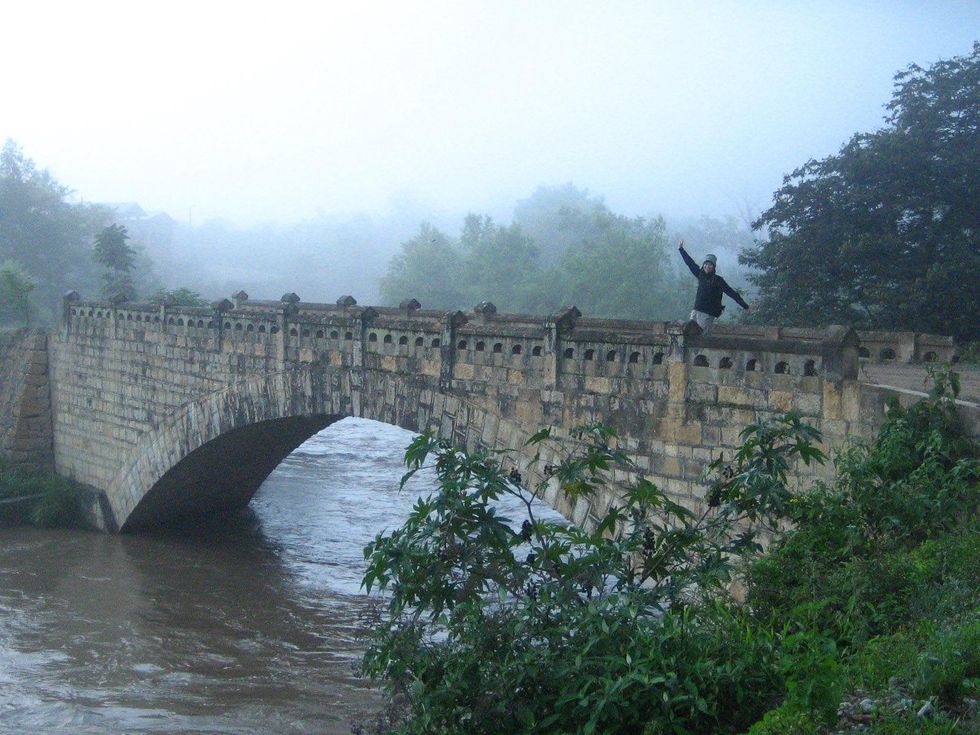

We spent the night in cramped quarters on the second floor of the only hospedaje in town. Starting at sunrise the following morning, we quickly descended to Old Tingo, where a few buildings remained standing along the torrential Rio Utcubamba. From here, a weathered stone bridge crossed a narrow tributary, the Rio Tingo.

We spotted a discolored trailside sign, pointing straight up at the steep slope ahead, Kuelap six miles!

A rough dirt track climbed out of the verdant valley and swung in arduous switchbacks up the arid mountainside. The rising sun burnt off the last pockets of cool air and we stuffed our sweaters into the backpack. The trail did not conceal the 4,000-foot elevation gain ahead and, along some stretches, ascended stone steps hewn into the incline. By midday our progress slowed, but the path leveled and a half-dozen adobe houses surrounded by low fences indicated we were getting closer.

Finally, emerging into an open expanse of green grass, cropped close by roaming goats and llamas, we schlepped our tired legs the final stretch to the immense walls of the fortress. After unabashedly restocking on sodas and chocolate at one of several wooden stalls lining the clearing, we sat on rocks in front of the main portal, a narrow, tall hallway shaped like an inverted V. Massive walls of limestone slabs, reaching 60 feet high, stretched left and right for nearly one thousand feet in length.

Much of the ruin site has not been fully excavated, leaving a sense of exploration. Nearly 400 buildings have been identified, many of them small circular structures, which were covered by thatch roofs while the city was occupied and may have served as living quarters. Other distinct structures we saw included El Tintero, or ink well, a funnel-shaped citadel and La Atalaya, a round tower at the northern corner of the site.

We wandered aimlessly for hours, climbing up and down half-buried stairs, inspecting carved friezes in stone walls, some representing deer and birds, but the most common were snake-like zigzag patterns.

Along the eastern wall of the ruins, the sheer mountainside dropped into a deep valley below and we perched on a slab, soaking in the sweeping views across the crumpled Andes. Terraced fields and farmsteads of minuscule houses clung to the slopes and strips of white dirt, footpaths, zigzagged through the dun colored landscape. I wondered whether any of these trails had been trodden by Chachapoyan farmers or builders, harvesting maize and potatoes or transporting rocks.

Looking back across the grounds, we could see the rough outlines of the structures still buried under the rank vegetation. The majority of buildings appeared to be of the same size and construction, a sign of an apparently egalitarian society. The imposing walls and narrow entrances suggested that the site served as a fortification, possibly against rival societies to the west, but anthropologists now believe that it functioned as a religious center.

Researchers estimate that less than five percent of Chachapoyan city sites, burial grounds, and sarcophagi have been excavated and studied, leaving much to be discovered and learned about this fascinating culture. For example, further south, tombs at the Laguna de los Cóndores, discovered by cattle ranchers in 1996, held more than 200 mummies and thousands of artifacts, now housed in the Museo Leymebambain.

Similar significant finds surely wait to be discovered. Chachapoyan society harbored elaborate beliefs and had intricate rituals to honor the dead. Even Kuelap holds human remains, some of them buried ceremonially, but others could have been last fatalities of war with the Incas.

Practical Travel Advice

In the late afternoon, even though we felt there was much left to be seen, we reluctantly started our return. One glance at the torturous path winding up the valley along dry ridges and slopes strengthened our resolve to hitch a ride down the mountain.

Researchers estimate that less than five percent of city sites, burial grounds and sarcophagi have been excavated.

Fortunately we caught up with the school group in the parking lot and they remembered us, sparing two seats in their overcrowded bus. We were exhausted and gladly listened to local pop music blaring at maximum decibels, as the bus lurched down the mountain. In some spots, I looked straight down the window at the side of the bus and did not see an inch of road, just a precipitous 2,000-foot drop, but quickly distracted myself by taking one last peek at the unforgettable ruins of Kuelap, receding from view on the mountaintop above.

From Peru’s capital, Lima, it is possible to board a bus, preferably first class, for the 22-hour trip to Chachapoyas. Dozens of other buses connect to larger cities to the north and south also, including Chiclayo and Trujillo on the coast. From Chachapoyas, it is possible to book tours to visit Kuelap and other ruin sites or hire a taxi to visit independently.

For the budget conscious traveler, colectivos are an even cheaper alternative to reach the ruins. The hiking option from Tingo is of course free, but more of an option for the energetic, with food stalls and basic supplies available at Kuelap. Guides are often not directly available at the ruin site, but we met two knowledgeable locals who were also visiting and they explained many details to us.