Art & Fashion

Strange & wonderful relationship between Menils and Charles James explored in new exhibit

Nasty and temperamental, Charles James scared off most of his well-heeled clients. But Dominique and John de Menil saw something different in the notorious designer: A touch of genius.

“My husband and I consider Charles James to be one of the most original and universal designers of this period and in this country. . . . Traveling as we do . . . we are amazed to see how many dresses from the Paris Couture actually can be traced back to Charles James," Dominique de Menil wrote in 1957.

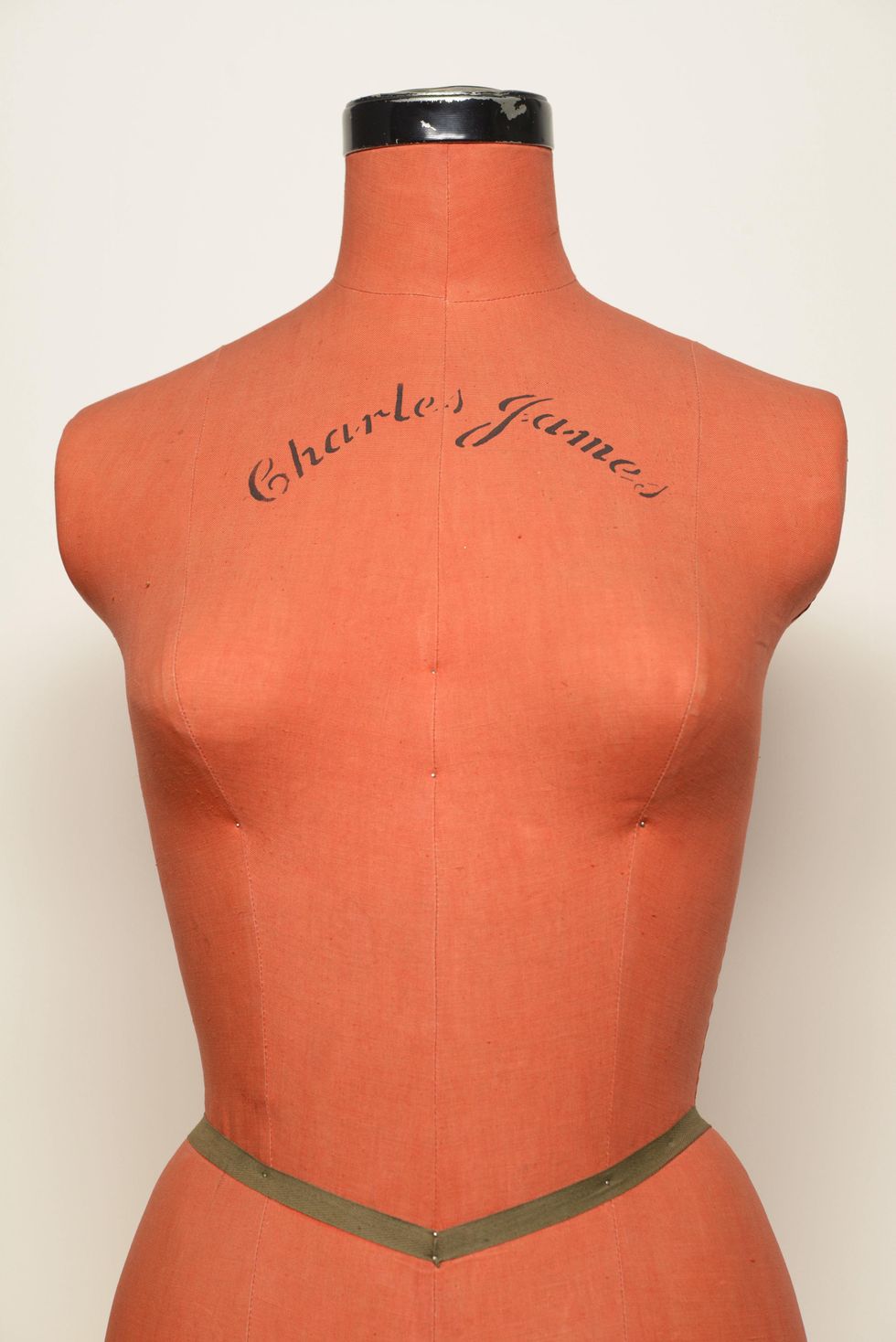

While James is being honored for his swirling, couture-quality designs with dramatic silhouettes that define glamour in a grand show at the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Institute in New York, observers are likely to learn more about what made him tick in an intimate jewel of an exhibit, A Thin Wall of Air: Charles James, on display at the Menil Collection, through Sept. 7.

"There's a kind of clarity. To have the clothes in that context really is marvelous," said Harold Koda.

It features 14 pieces of clothing, ranging from coats to ball gowns, that James designed for Dominique de Menil, presented amid several pieces of furniture he designed for the Menil's River Oaks home and priceless art, including the 1934 Max Ernst portrait of Dominique. The combination of clothing, furniture, sketches and artwork makes a strong statement about James' sensibilities and the de Menils' influence.

"It's very rare where you see the larger aesthetic," said Costume Institute curator Harold Koda, who visited the exhibit last weekend and participated in a panel discussion on James and the Menils. "Maybe the dresses that are there exist in variation in our collection (at the Met) — it wasn't as if Dominique had the only one— but there's still the lens of which everything gets filtered.

"There's a kind of clarity. To have the clothes in that context really is marvelous."

Clash with Johnson

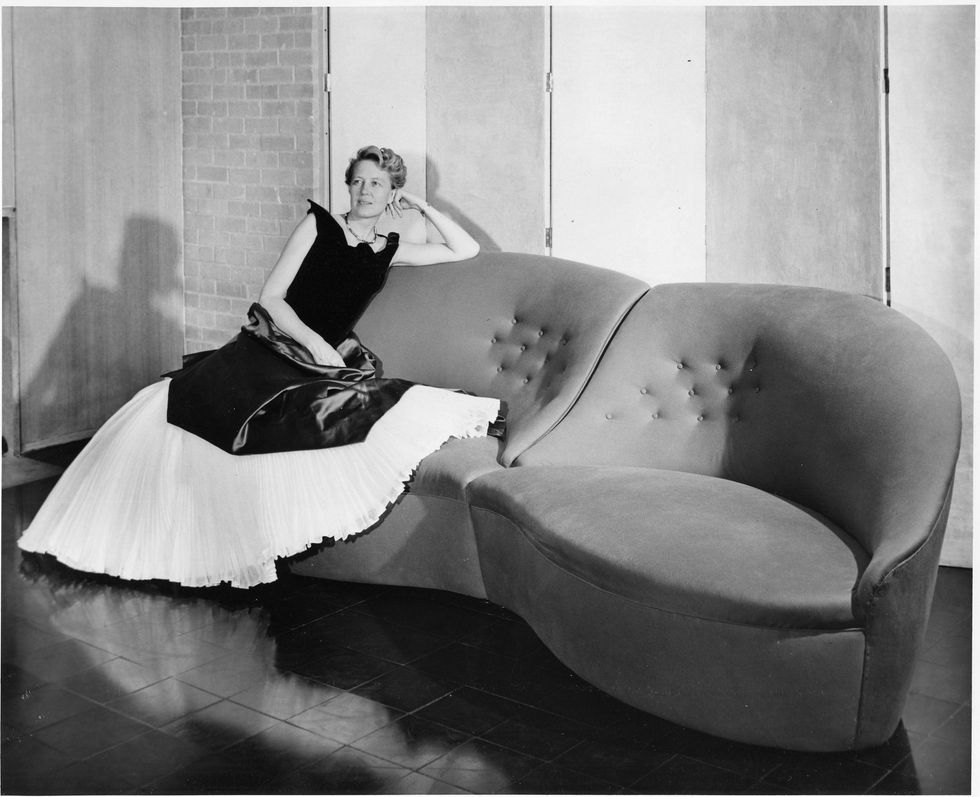

The Menils, who were patrons of James until his death in 1978, commissioned him in 1950 to create wildly-shaped and colored furniture for their ultra-contemporary River Oaks home, much to the chagrin of its architect Philip Johnson. (It was James' only residential commission.)

"Johnson was furious and James, of course, loved it," said William Middleton, who is writing a book on the Menils. "He has fun teasing Johnson. 'Now I'm going to create a Turkish patio, it's going to be very Middle Eastern.' This was at a time that Johnson was completely under the sway of Mies van der Rohe. The slightest curve was considered heresy."

Though James is known for his expertly-constructed ball gowns, de Menil did not own a lot of them. "She was a pragmatic patron," Sutton said.

Dominique once wrote about the new house, "You could see right away how we could get bored. And John, who was always full of creative ideas in the spirit of enterprise — dangerous ideas — thought of inviting James."

"James introduced felt and velvet walls in butterscotch, hand mixed paints in mauve, aqua and gray patina as though they were etched by time. He also created custom furniture with sweeping curves in an otherwise linear home," Menil assistant curator Susan Sutton told the audience at the panel discussion. Among his most noted pieces is a sofa shaped like a pair of lips.

The deep colors used in the home appear in James' fashion designs and both have a surreal, sensual quality that is in keeping with the sensibilities of the de Menils, who amassed a noted collection of Surrealists that is a cornerstone of the museum. And his obsession for detail in the structure and creation of a garment matched the Menil's quest for perfection.

"Among fashion professionals, he is known as a designer's designer, with his use of architecture and shape. He had a very muscular approach to design. He forces fabric into contortions that sometimes they don't want to take, " Koda said. "He strived for an absolutely state of perfection but that takes its toll."

James's abrasive personality "taxed the Menils as well," Sutton explained in interview, "so they put a little distance between themselves" in the late 1950s, although they continued correspondence in later years.

Saved clothing

To put the show together, Sutton and the curatorial team sifted through 55 James garments owned by Dominique de Menil, nearly half of which are too fragile to displayed in public. Though James is known for his expertly-constructed ball gowns, de Menil did not own a lot of them.

"She was a pragmatic patron," Sutton said.

The James-designed clothing in the exhibit includes a camel wool coat, designed in 1947, a red cluster gown, designed in 1949, a red fleece cape with dolman sleeves, a chocolate silk Infanta cocktail dress with a full skirt and a cutout neckline, and an opera coat made from saffron damask silk and lined in ice blue satin, most created in the 1950s.

While the de Menils donated money to the Brooklyn Museum to expand its collection of James pieces (the museum had begun to preserve his legacy as far back as the early 1940s and donated the collection to the Met in 2009), Dominique held back the clothing that James had made for her.

"She very much understood these were remarkable pieces of clothing. There's definitely the sense that she really quickly had the idea that this was a collection," Sutton said.

A month before her death in 1997, Dominique de Menil wrote about her desire to have a James exhibition in Houston, although she did not leave detailed plans. But it was clear that she considered James an artist who would stand the test of time.

"She talks in an interview about creating a corner in the museum for the James garments and that they would live amongst the other art," Sutton said. "She very much saw it as a part of the collection."