Tattered Jeans

The little girl in the church: A Hanna who sees darkness & hates Hannah Montana

Editor's note: Katie Oxford is on the ground and in the boats in Louisiana, reporting from the heart of the Gulf oil spill disaster. This is the fourth of her columns from the scene.

During my time in Louisiana, there were people who, like Russell Dardar, I was meant to meet. Here’s one who led me to another.

I met Arlene when Russell and I were first visiting. She drove up just shy of our shaded area, then backed up easy like as though she’d done it a thousand times blindfolded. She opened her hatchback and immediately (but not hurriedly) began unloading empty ice chests. I stood to introduce myself and explained that Russell had been kind enough to help me understand what was going on.

“This world could sure use more of that,” she said.

She’d come from the Live Oak Baptist Church just having served lunch to BP. “They liked my eggplant with shrimp,” she reported.

Arlene had been cooking for BP for the last week but explained that soon, someone else would be preparing their meals. “They hired a caterer from Thibodaux,” she told Russell, who briefly looked downward.

“But that’s OK,” she smiled, “Gives someone else a chance.” Such is her soul in the midst of much loss.

I’d sure like to know when you’re cookin’ that eggplant and shrimp again,” I smiled. “Well I’m cooking this Saturday to next Saturday,” she answered. “Dinner for six.”

I wondered if those six wore business suits or the kind I’d seen all week. Soiled.

“I’m hoping I might talk to some of them too,” I told Arlene.

“Well, if you go down to the Church right now, you’ll probably see a lot of people … it’s sorta like their headquarters.”

Little Girl in the dark

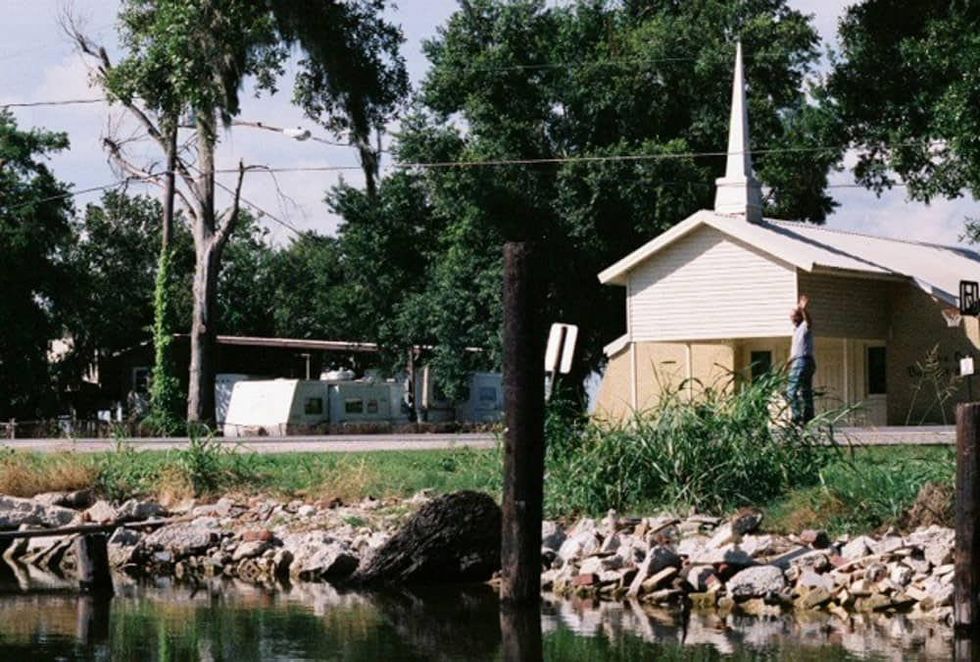

The Live Oak Baptist Church was less than a quarter of a mile away but as so often happens, I’d pulled over to explore a few things along the way. By the time I turned into the church parking lot (late afternoon) there wasn’t a car or person in sight.

The door of the church was unlocked so I opened it to a sudden blast of air conditioning and an unexpected darkness. No lights were on — only natural light, still strong enough to break through glazed windows and allow a view of the room. Empty, except for one little girl standing in the middle, sweeping the floor silently with a broom much bigger than she.

“Hanna Smith,” she told me shyly. After that, shyness vanished. Only a little girl seemingly very lonely and bubbling over with enthusiasm that someone, even if a stranger, was there with her and listening to every word. Trying anyway.

“Don’t you love your name?” I inquired.

“Not really,” she said immediately.

“You know what most people call me?” she asked and not a breath later answering, “Hannah MONTANA!”

I thought how many little girls would love to be called that and wondered why this Hanna did not. “Have you ever SEEN Hannah Montana?” she asked, her eyes growing big.

I was more curious now but Hanna, still holding her broom, had other matters on her mind … moving across like lightning.

“I’m not suppose to be in here so we have to be quiet,” she said softly. “My mother doesn’t like me to do this but I like to clean.”

I looked down at the neat little piles of dirt that Hanna had so carefully compiled and understood completely.

“You know I’m the same way,” I told her. “There’s something very soothing about sweeping.”

In the course of 20 minutes and seemingly told in a single breath, Hanna covered her siblings ... how annoying they can be — spelled her mother’s name — described what her father looked like — she’d come from Arkansas, a place she seemed to like as much as Hannah Montana — other things I don’t remember.

I wanted to pull my notebook out and write her words, take out my camera and snap her picture but I knew better. My purpose was to listen to Hanna — and the more she spoke the fuller my heart filled with empathy.

“We’re having a service tonight at 7 that’s all gonna be in French! ... Why don’t you come!?”

“Oh I’d like that,” I replied, “but you know what? I don’t see well driving at night so I have to be heading back before dark."

“You know once I couldn’t see either!” she said. “My Mama popped me with a dishtowel about 10 times…my eyes started burning ... my right eye’s not good.”

Then, suddenly as though lightning crossed again, “If you come tonight, maybe God will give you sight to drive back!”

"You’re right, Hanna, He probably would, but you know I’m afraid I still have to go. I’m sorry. I’ll be back, though and maybe I can attend a service then.”

“Maybe when you come back,” Hanna said, her eyes growing big again, “we can walk on the levee!”

“I’d like that.”

Interrupting a meal with dad

Like leaving Louisiana, it was hard leaving Hanna. There seemed to be so much more she needed. Maybe I did too.

I promised her that we’d see each other again and soon. She walked with me just to the door of the church and pointed to her house nearby. I told her I would knock there. She hurriedly began explaining if there wasn’t a car underneath the house — where I should look for her next. “Hanna” I interrupted, resting my hand on her shoulder gently, “I’ll find you.”

“By the way,” I inquired, stepping back slightly, “What does your T-shirt say?”

“My Mama dudn’t like it,” Hanna said.

The top portion (all in caps) was easy to read. “P.O.L.I.C.E.,” I spelled. Then Hanna recited the words underneath with calm unspoken until now. “Preach to Others the Love we share in Jesus Christ, everyday.”

A few days later, after the boat tour on Russell’s skiff, I knocked on Hanna’s door. A bald man with a grayish beard opened the door saying, “Yes?” I introduced myself and asked if Hanna was home. He identified himself as her father and, somewhat reluctantly, invited me in. At the far end of the room I saw his wife and three or four children (two in highchairs) sharing a meal.

Hanna instantly jumped up and ran over — stopping short, though, as if suddenly remembering something.

I apologized for interrupting but explained to her father that Hanna had been so kind a few days before showing me the church and inviting me to the service all in French. I looked at Hanna, holding her hands as though washing them with a bar of soap and staring up at her father like Courage The Cowardly Dog.

“I hope you’ll be having the service again soon,” I continued. “Oh no,” he chuckled with relief, “not that one anyway ... Hanna, tell the lady about our next service.”

Similar to how a nurse might say to a nursing home resident, “tell her what you had for lunch today.”

Hanna, still looking wary and rubbing her hands said something quietly, prompting him to announce, “It’s the Cowboy service.” Hanna’s mother who’d slowly walked over from the table and stood behind her daughter — returned just as silent.

“Well, I’ll let ya’ll get back to your meal,” I insisted, “but Hanna, I’m so glad I got to see you again.”

She smiled back sweetly. “May I give you a hug before I go?” I asked.

I’d hardly finished the question before she was in my arms — holding onto my neck the same way I used to hold on when climbing a tree.

“Was that you in the boat with Russell today?” the father asked as I walked out the door.

“It was,” I answered.

I realized then he was the man putting a garbage bag in a container that morning. I’d watched as he walked back toward the church then suddenly, turned around half way and waved to us like we’d just hollered hello.

I pictured Hanna sweeping again in the empty dark church ... with light still strong enough to break through those windows.

Other articles in Katie Oxford's Louisiana series: