Fast trains, slow politics

Is Texas finally ready to jump aboard a high-speed rail? Going faster takes along time

After missing out on the last round of funding, Texas is finally in a position to spend some of the $53 billion the Obama administration recently proposed for a high-speed rail. Boasting five of the country’s 20 largest cities, separated only by an abundance of wide-open space, Texas practically goads engineers to conquer it.

Yet, unless someone invents a bullet train that can tear through the fabric of space-time, Houston travelers shouldn’t plan on taking 40-minute trips to Dallas any time soon.

Third Time’s a Charm

All the conjecture about American high-speed rail systems, their practicality and their cost would look a lot different if a group of private investors had succeeded in building one 20 years ago. Back then. a consortium of train manufacturers and banks won a franchise from lawmakers to build the “Texas T-Bone” route linking Houston, Dallas and San Antonio. But trouble raising $5.6 billion in financing and a fight with airlines like Southwest deep-sixed the project by 1994.

While European Union countries Japan and China spent the ensuing years breaking speed records with ever-faster trains, stalled projects like the one in Texas left the American public without any frame of reference as to what an American bullet train network would look like, let alone how much it would cost to build. By the time President Obama opened a new trove of federal funding and public attention for high-speed rail last year, Texas hadn’t even adopted a passenger rail plan detailed enough to qualify for the money.

This time around, the state is ready. With an updated rail plan that was approved by the Texas Transportation Commission in November, TxDOT rail director Bill Glavin says his office is eager to “apply for everything and anything we can get our hands on”.

Decision Points

Dramatic as it is to imagine lithe, space-aged locomotives whistling across the Texas prairie at the speed of a Bugatti Veyron, it’s important to note what winning those federal dollars would actually look like. States that have already ironed out much of the complex planning for new lines could use federal money for construction. Texas’ share, though, initially would go toward more studies on ridership, potential routes, cost and how much relief it could bring to highways and airports.

Even if the proposed rail funding survives the current cost-cutting Congress, it would take at least a couple of years before the state would be ready to approve actual construction projects.

In the meantime, Glavin’s office is more than happy to wrangle all the research and present it to the Legislature. At that point, lawmakers will have a few options to consider. One scenario could involve dedicated tracks and electric trains like those in Japan, capable of speeds in excess of 200 miles per hour. A slower, but simpler, option would add capacity to existing freight railroads to accommodate more passenger trains at higher speeds.

Glavin points to improvements in the tracks between St. Louis and Chicago that have enabled speeds up to 79 miles per hour. Amtrak trains could potentially reach 110 miles per hour on dedicated tracks.

“It all can fit within existing right-of-way that Union Pacific has,” Glavin said. But he also noted that adding tracks and upgrading crossings would involve significant costs. Likewise, curves in existing rights of way would limit top speeds.

Then there’s the question of where the train should run. The federal government’s “high speed rail corridors” around the county would link Houston to a hub New Orleans, but not to Dallas.

The feds’ priorities continue to evolve, though, and the regulations for the most recently proposed round of rail spending haven’t been developed yet. Glavin said that if the emphasis shifts to connecting cities of two million people or more, situated less than 500 miles from each other, the state’s earlier plans linking Texas’ three largest metropolises may gain more traction.

What’s Next

Even if plans for high-speed rail gel in Texas, the average traveler is unlikely to notice for a very long time. Over the next five years, Glavin indicated that his office’s most visible work would continue to be commuter rail projects and efforts to improve the safety and efficiency of freight lines.

Recently, the chairman of Japan’s largest railway dazzled the Greater Houston Partnership with the prospect of a privately financed high-speed rail line from Houston to Dallas. Yet even with private money freeing the project from the political roadblocks associated with tax-payer funding, it would take at least a decade to build.

Like any transportation project of that magnitude — think new airports, freeways or light rail — going faster takes a long time.

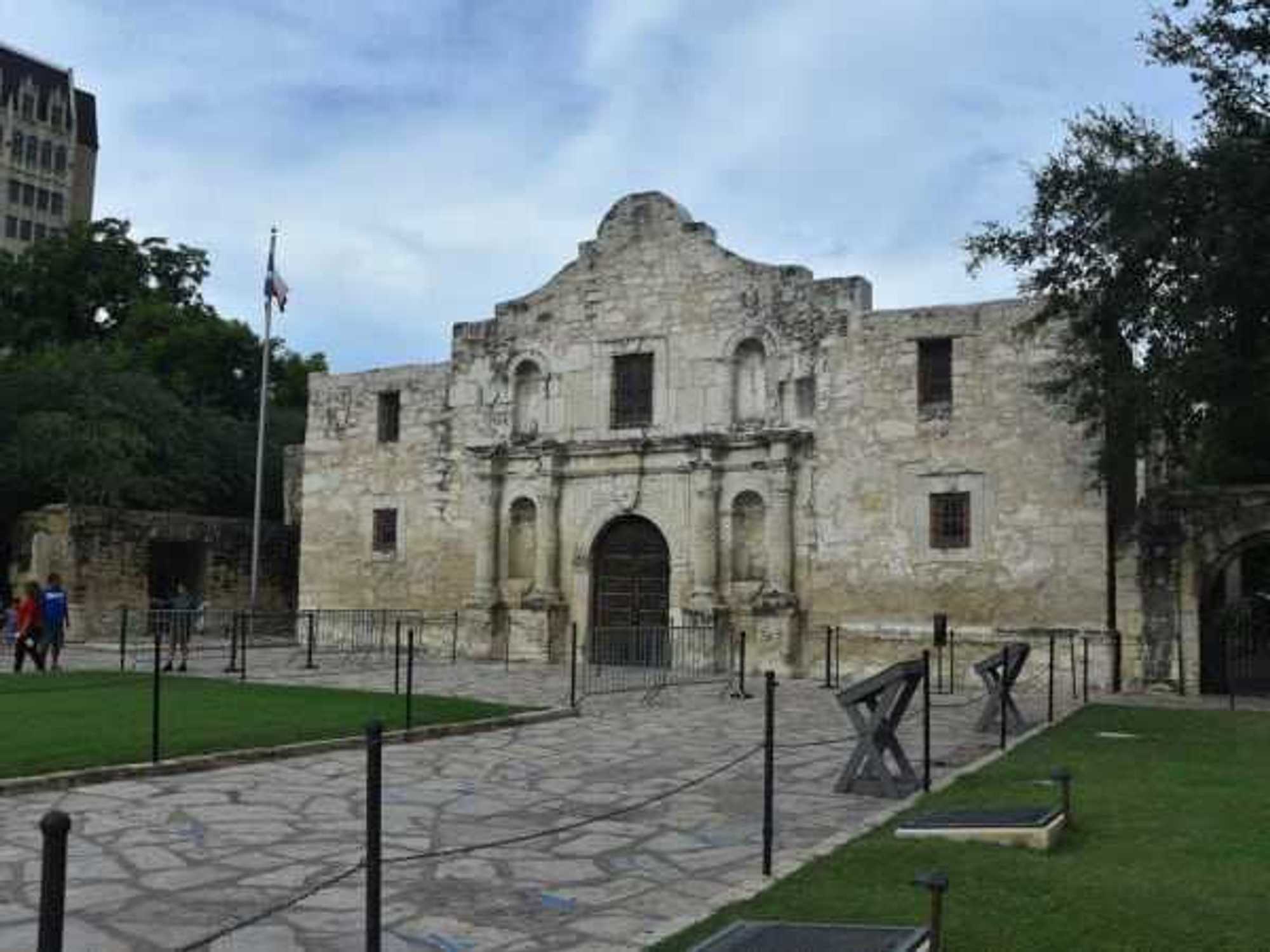

This Alamo artifact gives an idea of what the cannon will look like once restoration is complete.Photo courtesy of the Alamo.

This Alamo artifact gives an idea of what the cannon will look like once restoration is complete.Photo courtesy of the Alamo.