Cinema Arts Fest Insider

A wrongly convicted man's nightmare ends in An Unreal Dream

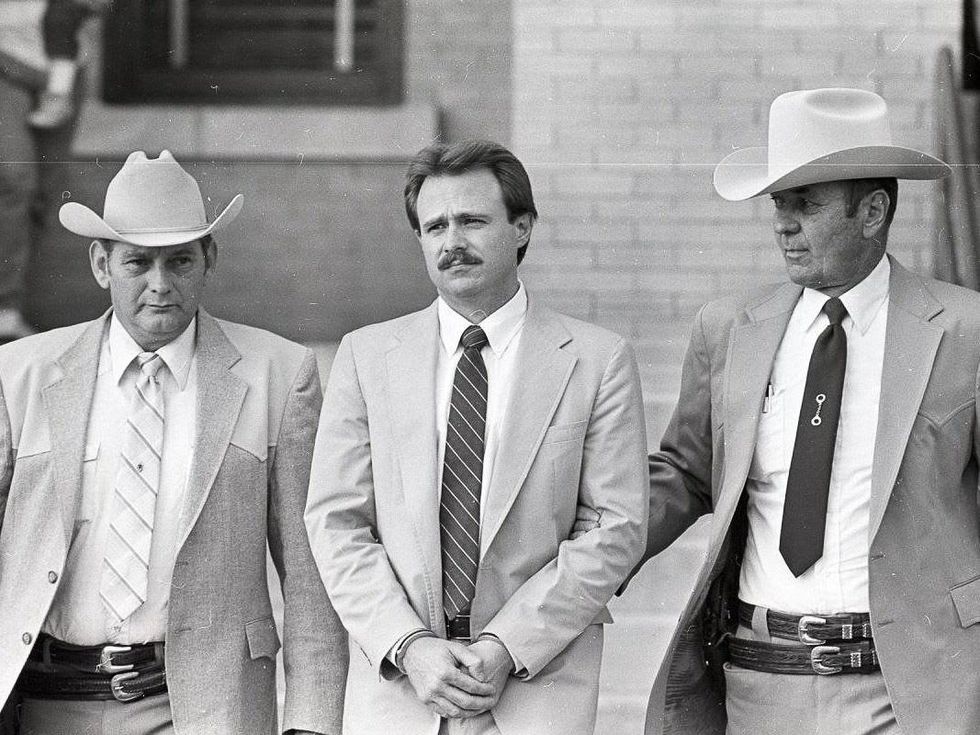

Talk about great timing: An Unreal Dream: The Michael Morton Story, Al Reinert’s stirring documentary about the wrongful conviction and ultimate exoneration of a Williamson County man accused of brutally killing his wife, will be screened by the Houston Cinema Arts Festival at 7 p.m. Sunday – just two days after former Williamson County district attorney Ken Anderson agreed to serve 10 days in prison for his prosecutorial misconduct during Morton’s 1987 murder trial.

For the benefit of those who tuned in late: Morton, then gainfully employed as an Austin grocery store inventory manager, was convicted (mostly on the basis of circumstantial evidence) of beating his wife Christine to death in their home – allegedly in front of their 3-year old son.

Mind you, the youngster actually told an investigator that his father was not home at the time of the slaying — and that someone else, described by the child as “a monster,” really killed his mom. But this evidently meant little to Anderson. The prosecutor never gave a transcript of the child’s interview to Bill Allison, Morton’s defense lawyer. Nor did he turn over other evidence that might have persuaded the jury not to render a guilty verdict.

Thanks to the efforts of Houston attorney John Raley and members of the New York-based Innocence Project, Morton finally was freed from prison in 2011 after DNA testing exonerated him.

Thanks to the efforts of Houston attorney John Raley and members of the New York-based Innocence Project, Morton finally was freed from prison in 2011 after DNA testing exonerated him —and, not incidentally, implicated Bastrop dishwasher Mark Alan Norwood, who was convicted of Christine Morton’s murder in March of this year.

Morton received his guilty sentence just a few days after An Unreal Dream had its world premiere at the SXSW Film Festival. Director Al Reinert — a two-time Oscar nominee as documentary filmmaker (For All Mankind) and Hollywood screenwriter (Apollo 13) — was on hand with Morton and Raley to introduce his movie at the Austin event. He’ll also be with them to answer questions after Sunday’s HCAF screening at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Reinert phoned me a few days ago from his new home in Wimberley (where he recently moved with his wife, actress Lisa Carroll) to discuss An Unreal Dream – which will air Dec. 5 on CNN – and to share his thoughts about the extraordinary man at the heart of his exceptional film.

CultureMap: At what point did the Michael Morton case pop up on your radar as a potential subject for a documentary?

Al Reinert: Pretty much around the time Michael got released from prison. I had a couple of friends who had told me about this story. And while I was living in Los Angeles at the time, I was able to watch him on the Internet. I’d already known a little bit about the case – but, really, it didn’t seem all that different to me. I mean, he’s not the only person who’s been wrongly convicted and then exonerated with DNA. It’s just that I had a friend who knew John Raley, and told me this was an especially interesting case, and I should be paying attention to it.

So I saw Michael on the day he was released from prison. And I saw him on camera talking for the very first time – he was interviewed on TV that day, and we even have a little bit of that in the film. And right away, I thought this is not your average guy. This is an interesting guy. He’s got a certain charisma to him. And I kind of wanted to know more. So about a month later, I flew to Houston to meet John Raley, and had lunch with him, and started to learn more about this story. And the story kept getting more interesting the more I learned about it.

CM: The remarkable thing about Michael Morton – this comes through in your film, and when you meet him in person – is that he seems so remarkably composed and equanimous for someone who spent 25 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. He comes across as someone who is so – well, there’s no other word for it – forgiving.

AR: He does. And it is remarkable. I know I couldn’t do it. Even if I could say the words, I couldn’t pull it off like he does. He’s very genuine about it. I think he came to terms with it while he was still in prison. And I know he gives a lot of credit to his Christian faith. I mean, he doesn’t talk a lot about Christ or Jesus that much. So it’s almost like a Zen kind of a thing. But I think he really did become a different person while behind bars.

CM: What about you? Did you find yourself getting angry while you were researching this case?

AR: Oh, sure. All of us who worked on the film were angry. Because a lot of this was still going on during the production. You had Ken Anderson basically blaming the system instead of himself. And the more we learned about it, the more everybody but Michael got angry.

To think that a Tea Party legislature could unanimously pass a reform bill that’s one of the strongest in the country – it’s just amazing. I don’t know how to account for it, other than the fact that a lot of these Tea Party types listened to Michael and believed his story.

CM: Largely because of the injustice he endured, the Texas legislature last May passed the Michael Morton Act, which requires prosecutors to give defense attorneys any evidence relevant to their clients’ cases.

AR: Yeah, I know – it’s been one astonishment after another with this case. To think that a Tea Party legislature could unanimously pass a reform bill that’s one of the strongest in the country – it’s just amazing. I don’t know how to account for it, other than the fact that a lot of these Tea Party types listened to Michael and believed his story. And it moved them. I know he lobbied for it pretty hard. It wasn’t like he was off in the sidelines while this bill that was named for him was floating around the capital.

CM: The bill passed less than two months after An Unreal Dream premiered at South By Southwest. Did you screen the movie for many lawmakers in Austin?

AR: We never actually had a screening specifically for legislators. But I do know we invited them to any screening we had – including the one at South By Southwest. And I know Michael always carried around with him tickets to any screenings we had in Austin, so he could hand them out to any legislators we met. But I can’t say I kept track of which ones attended, and which ones didn’t.

CM: I would assume you’ve been following the ongoing story of Ken Anderson’s… well, shall we say, fall from grace?

AR: Yes. And it’s well deserved.

CM: Did you try to interview him for the documentary?

AR: Oh, sure. We tried to get him and [former Williamson County district attorney] John Bradley as well. But at the time we made the movie, there was this gag order in place as soon as they indicted Mark Alan Norwood, the guy who was tried and ultimately convicted of killing Christine Morton. Because some of the guys in our story were clearly going to be witnesses in that case, the judge in the Norwood trial – who was buddies with Anderson anyway – issued a gag order.

The people who were Michael’s friends chose to ignore it and did interviews. And the people who were not Michael’s friends – i.e., Anderson himself, and Bradley – basically said, “Well, there’s a gag order, we can’t talk to you.”

CM: When did you film the interviews for An Unreal Dream?

AR: Most of the main interviews we did over Memorial Day weekend last year. That was our first weekend of shooting, really. And here’s the thing: We went in search of an old-fashioned kind of courtroom, because we wanted to put Michael in a courtroom that had that kind of To Kill a Mockingbird feel to it. And we scouted about a dozen courtrooms in Texas looking for one that looked right. And it turned out that the best-looking one of all was the one in Georgetown — where the original trial had actually happened.

We did not go there first. But we were fortunate, in that that courthouse is now a museum, as opposed to a working courthouse. Which meant the courtroom was available to rent. But you could only do that when the museum wasn’t open. And on Memorial Day weekend, they were closed for three days. So we were able to take over the courthouse, and shoot in there. That’s where we filmed Michael and John Raley and [defense lawyer] Bill Allison and the two jurors. Probably the heart of the movie was filmed that very first weekend.

Right there where it all happened.