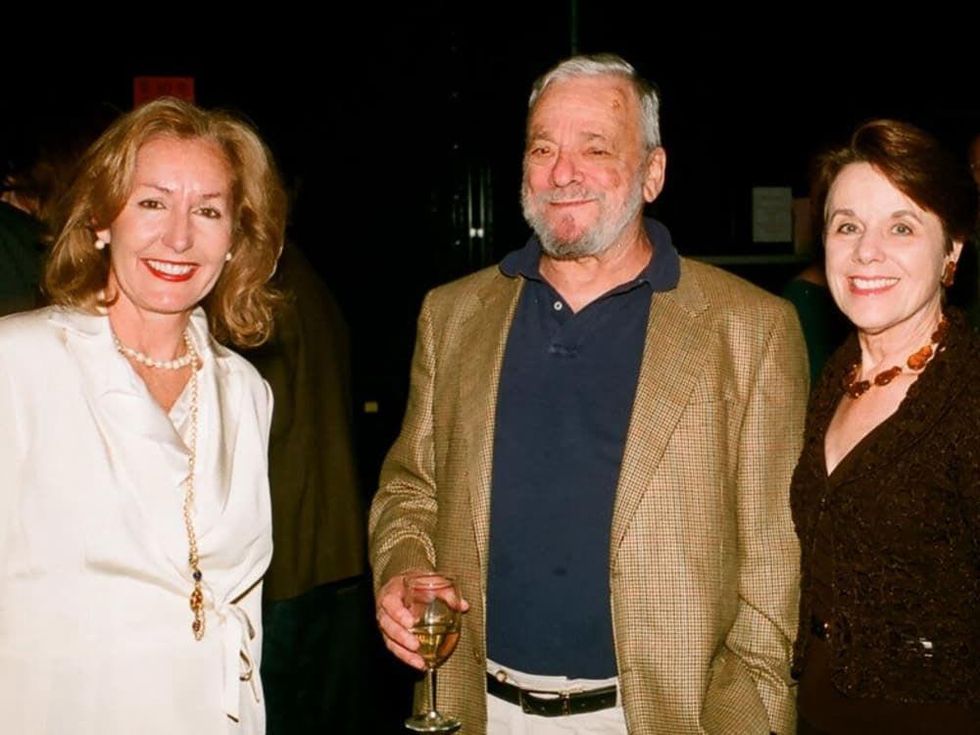

When Stephen Sondheim was in Houston for the Houston Grand Opera production of Sweeney Todd in the 1980s, he barely spoke to those outside his inner circle at parties around town. But when he recently returned to participate in a conversation with New York Times columnist Frank Rich at Jones Hall, the iconic Broadway composer couldn't have been nicer. He seemed genuinely touched by the outpouring of affection from Houston fans who attended a private backstage reception hosted by Society for the Performing Arts and engaged in long conversations with several admirers.

Everyone might have been in good spirits because Ziggy Gruber of Kenny & Ziggy's had a table load of deli food at the reception. Gruber said business at his Post Oak deli had jumped 50 percent since his September appearance on the Food Channel show, Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives.

Sondheim and Rich got a standing ovation from the audience when they walked onstage for An Evening with Stephen Sondheim. But the cavernous symphony hall was not conducive to an intimate conversation. Sondheim also mumbled a lot, so it was hard to understand everything he said during the 90-minute program. But he did impart a few nuggets of wisdom to aspiring Broadway composers.

He told the audience the opening number can make or break a show. He cited A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, where he turned a flop into a hit by coming up with a new opening number, "Comedy Tonight."

"If you have the first right first five minutes, you can coast, " he said.