Mondo Cinema

Muscle Shoals crosses racial divide to show how music was made with heart and soul

Is Muscle Shoals, Alabama hallowed ground? Could be. Early in Muscle Shoals, the endlessly fascinating and hugely entertaining documentary set to screen Monday and next month at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, we hear of the local legend about a female spirit in the nearby Tennessee River whose singing, according to Native American myth, can be heard by anyone with the heart to listen.

So maybe there’s always been some sort of supernatural influence to at least partly explain why this small Alabama town has loomed so large since the late 1950s in the history of recorded-in-America popular music.

Still, director Greg Camalier makes it very clear throughout his earnestly respectful and beautifully photographed film that whatever magic resulted in Muscle Shoals recording studios when Aretha Franklin, The Rolling Stones, Jimmy Cliff, Wilson Pickett, Lynrd Skynyrd and other notables laid classic tracks can be attributed to resourceful mortals like Rick Hall and Roger Hawkins.

Hall, a hearty yet melancholy septuagenarian (at the time of filming) who bestrides the movie like a folksy colossus, is the guy who started it all back in the day when he founded FAME Recording Studio – originally with two partners in Florence, Alabama – and in 1962, after going solo and relocating to Muscle Shoals, charted his first hit single, Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On.”

Muscle Shoals is a sheer delight for anyone at all interested in popular music and music makers, a history lesson with heart and soul that deserves an A-plus.

That was followed by a stream of other hits – including Wilson Pickett’s “Land of a Thousand Dances,” Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” Aretha Franklin’s “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I loved You)” – many of them recorded in astonishingly brief sessions where improvisation was encouraged, but, judging from what we see and hear here, Hall always had the final word.

Muscle Shoals is by turns amusing and provocative as it deals with the irony that, even as Hall oversaw the efforts of African-American recording artists, he backed them when singular funky (or, as Franklin appreciatively describes them, “greasy”) session musicians who were conspicuously, and exclusively, Caucasian. (When Paul Simon called out of the blue, hoping to temporarily hire what he assumed were the black musicians in Hall’s in-house rhythm section, he was warned: “These guys are mighty pale.”)

Hall and other on-camera interviewees insist that the racial make-up of the FAME rhythm section was not a result of racism, and that white and black artists treated each other as equals in the studio. (Clarence Carter suggests that, in the early ‘60s, FAME was one of the very few places in the Deep South where he could freely address a white man by his first name.) Indeed, Hall comes across as remarkably enlightened for a white Southerner during a period in Alabama when Gov. George Wallace was proselytizing for “segregation forever.” From time to time, Hall admits, he felt “somewhat frightened” when he would take black musicians out to dinner after recording sessions.

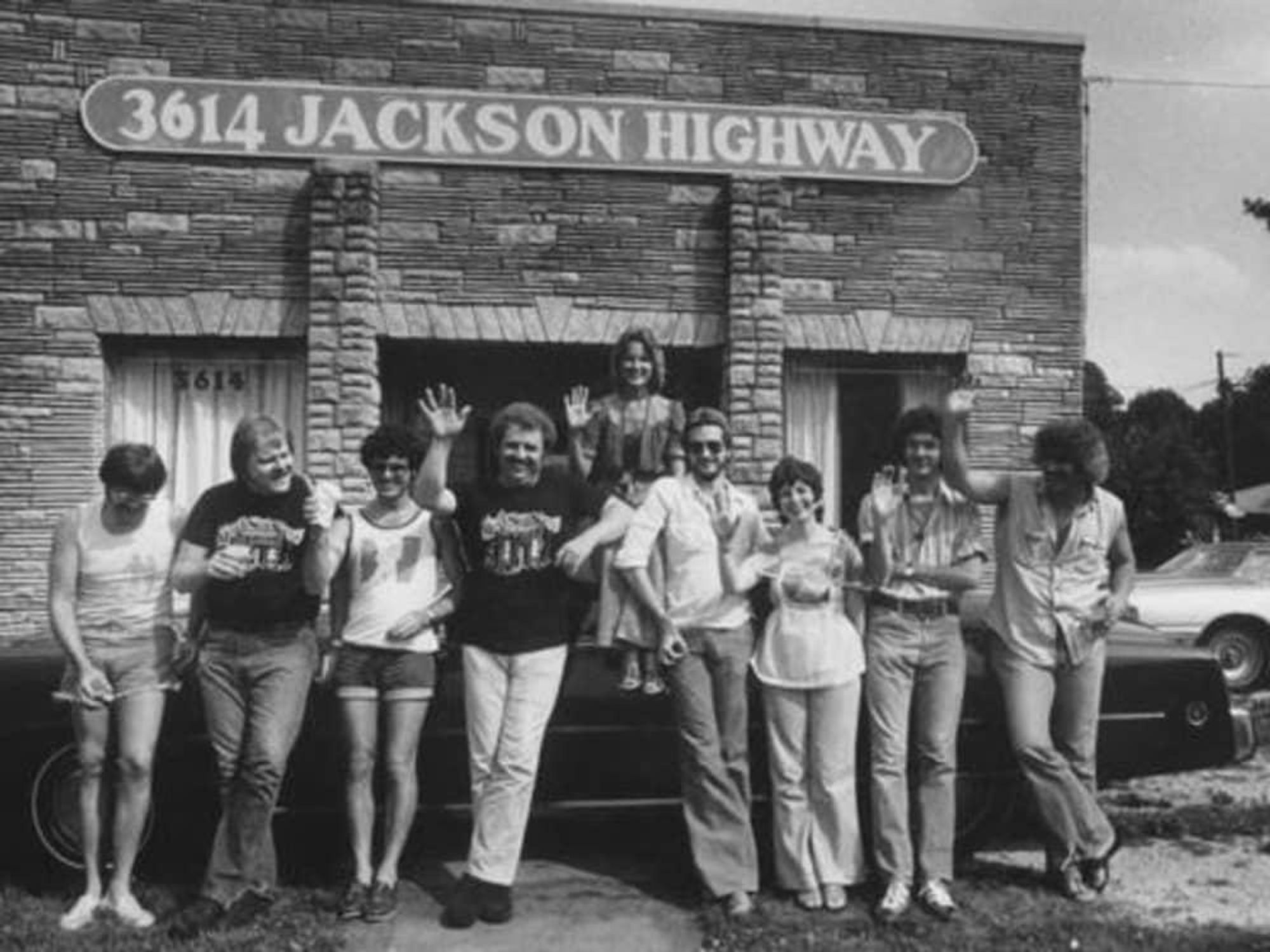

On the other hand, as Muscle Shoals takes pains to point out, Hall did hire an integrated lineup for The FAME Gang, the rhythm section he assembled when drummer Roger Hawkins and other musicians left FAME to establish their own arguably even more successful enterprise, Muscle Shoals Sound Studios. (Yes, you guessed it: Members of this the splinter group are the Muscle Shoals “Swampers” referenced in Lynrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama.”)

Even as it acknowledges racial divides, however, Muscle Shoals repeatedly emphasizes that the music famously recorded at both Alabama facilities represents a strikingly diverse cross-section of musical genres – R&B, pop Southern Rock, country, you name it, it’s been recorded there. The town itself is depicted as the center of what John Paul White of The Civil Wars describes as “a perfect storm” of interracial and international influences.

Just as important, Camalier’s documentary abounds in amusing and enlightening anecdotes about legendary Muscle Shoals recordings. Topics range from the inspired inclusion of a classical pianist’s riffs on Lynrd Skynrd’s “Freebird” to the late Duane Allman’s convincing an initially skeptical Wilson Pickett to cover The Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” Steve Winwood, Gregg Allman, Jimmy Cliff and Wilson Pickett are among the other interviewees with similarly engrossing stories to tell

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards describe themselves as being early admirers of “the Muscle Shoals sound” – The Rolling Stones actually covered “You Better Move On” back in the ‘60s – and delight in recalling the creatively free-wheeling Muscle Shoals Studio sessions that resulted in “Wild Horses” and “Brown Sugar.” But when one of the studio founders claims that these sessions were drug- and booze-free, Jagger can only smile and politely demur, while Richards in effect says, well, maybe compared to their usual recording sessions…

Camalier occasionally strives too hard to give his movie about music a visually lyrical quality, and Bono stands out among the on-camera interviewees for a similar sort of self-consciousness. But never mind: Muscle Shoals is a sheer delight for anyone at all interested in popular music and music makers, a history lesson with heart and soul that deserves an A-plus.

Muscle Shoals will be screened at 7 p.m. Monday, and again Nov. 26-29, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The film also is currently available on VOD.