Mondo Cinema

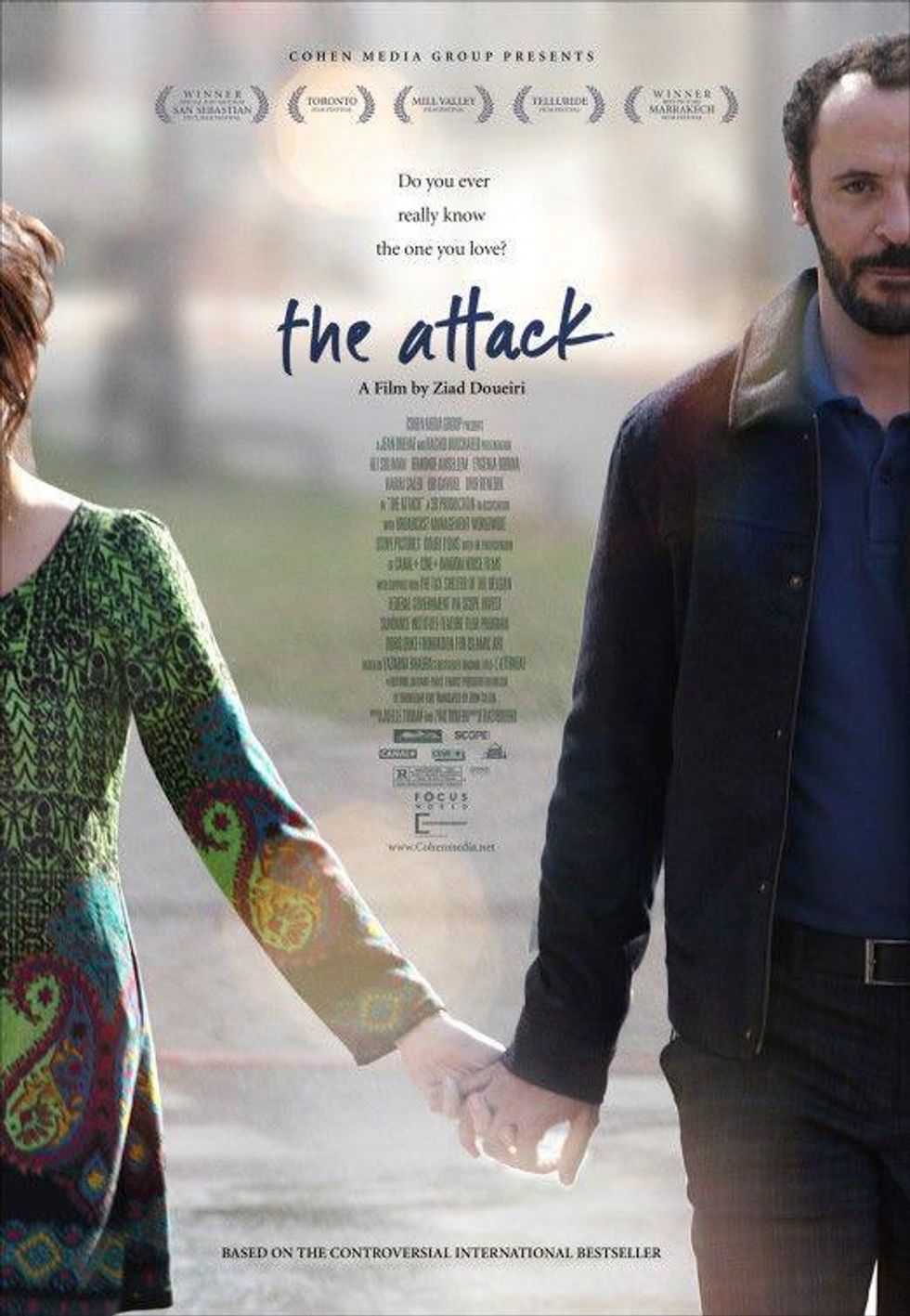

Controversial filmmaker defies an Arab League ban, examines suicide bombing: On The Attack

Like many other filmmakers who deal with potentially controversial and politically incendiary subject matter, filmmaker Ziad Doueiri hoped for the best, but expected the worst, as he prepared to launch The Attack.

He wound up getting a bit of both.

Critics started raving about The Attack (now playing at Houston's Sundance Cinemas) last fall during its initial rollout on the international festival circuit, praising it for the intelligence of its screenplay, the precision of its performances and the even-handedness of its insights.

Based on a novel by Yasmina Khadra, the drama focuses on the rude awakening experienced by Dr. Amin Jaafari (Ali Suliman), a Palestinian surgeon who feels safely assimilated in Tel Aviv, and far removed from ongoing Arab-Israeli tensions. But his comfortable world is torn asunder when Siham, his wife, is killed during an explosion at a popular restaurant — and identified by authorities after the fact as the suicide bomber responsible for the tragedy.

"I like it when you take your character and throw him in a situation that is much bigger than him, especially on the social level. Man versus the whole society."

For Doueiri, a Paris-based, Lebanese-born writer-director who studied filmmaking in the United States, and began his career as a camera operator for Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction), The Attack has represented a major professional turning point, the fulfillment of the bright promise displayed in his first two dramatic features: West Beirut (1998), an award-winning coming-of-age drama based on his own experiences as an adolescent during the 1975 Lebanese civil war; and Lila Says (2004), an erotic tale of young love in a Marseilles ghetto, which Doueiri co-wrote with his wife and frequent collaborator, Joëlle Touma.

Unfortunately, The Attack also has served for Doueiri as a brutal reminder that, when a filmmaker deals with real-world conflicts, his film can trigger responses far worse than thumbs-down reviews. By shooting his film in and around Tel Aviv, and by casting Israeli actors (including Reymond Amsalem, who plays Siham) in key roles, he aroused the ire of the Cairo-based Arab League, which encouraged 22 Arab nations — including Lebanon — to ban The Attack.

That’s the bad news. The good news is, The Attack is shaping up as an art-house hit in the United States, and actually appears to have benefited from the publicity generated by the Arab League boycott. Indeed, the movie has attracted so much attention, Doueiri now has a Hollywood agent, and has begun to field offers from major studios.

And, of course, he’s continuing to talk with the press about the movie that has done so much to elevate his profile.

CultureMap: In your first dramatic feature, West Beirut, you allowed the audience to view the 1975 Lebanese civil war through the eyes of a rebellious but largely apolitical teenager. In The Attack we get a glimpse at a similarly fractious conflict through the eyes of another observer who doesn’t feel immediately connected — at first — to what he’s observing. Coincidence?

Ziad Doueiri: Well, you know, it’s funny: I’ve been sent a lot of scripts recently by the studios after they saw The Attack. And I found most of those that they’ve sent me were not interesting, because they were about action and plot, and not so much about psychology. See, I like it when you take your character and throw him in a situation that is much bigger than him, especially on the social level. Man versus the whole society. Man versus The Establishment.

In The Attack, and in West Beirut — and in Lila Says, though on a more intimate level — I like to pitch my characters against something that seems almost insurmountable. Maybe it’s because while I grew up, I felt like an individual fighting an entire system. But whatever the reason — it’s certainly not conscious, it’s not what I decide that I’m going to show. So maybe it’s second nature.

CM: The Attack is a story that suggests we should never assume we know everything about anyone, even the people closest to us. Dr. Amin Jaafari, your protagonist, really is quite astonished by what he learns about his wife, isn’t he?

ZD: Yes. But when [co-scriptwriter Joëlle Touma] and I sat down to write the script, we decided at the start that we didn’t want to show this man as so selfish that he didn’t pay attention to his wife. Quite the opposite. He was thoroughly idealistic — he was not selfish. He believed that building a bubble around his family is his way of bringing happiness to the family. But the thing is, in real life, we know that, in a couple, someone’s view of happiness is not necessarily shared by the other person, or vice versa. What you think makes your wife happy — she’ll not necessarily see happiness in it.

He meant well. He had this idealistic view: “I can build a wealthy family, be very successful during this conflict. And as long as I keep the conflict away from home, I’ll be fine.” He believes that as a citizen who took the Hippocratic Oath to save lives, that’s going to save him from the whole Middle Eastern conflict. And he finds out at the end that the conflict is going to seep back into his life.

CM: Would you say The Attack is, on one level at least, a detective story?

ZD: That’s one dimension. The other dimension is, in couples — you don’t really know the person you want. We tried to take the film in that direction: He thought he knew her. He idolizes her. And progressively during the film, his image of her starts to break down, and he starts to remember things that did not go well between them. See, the film is in two sections. In the first part, he’s thinking of her in very romantic terms. And then slowly, that idea starts to decompose , and starts re-examining their past.

And he’s investigating on different levels. He’s investigating the perpetrators who made his wife do this thing. But he’s also investigating, retroactively, the truth of his marriage to this person. So it’s personal, and it’s political. We tried to constantly blend those two.

CM: Given your own background, was it easy for you to identify with Jaafari?

ZD: Yes and no. After all, the doctor in the film — it’s not like he emigrated from Palestine and went to study in the States. He left Palestine and moved to Israel — the place that is in conflict with his birthplace. I left Beirut in 1983, and I went to the States. The States is not directly, or indirectly, responsible for the problems in Lebanon. Had I moved from Lebanon to, say, Syria for example, or to Israel, that would be a different story. Dr. Amin Jaafari left a country and moved to the country next door. So he’s in a battlefield. And it’s impossible to escape the dilemma.

CM: I was working for The Houston Post here in H-Town when the paper shut down in 1995. And because it had been in shaky financial shape for a long time beforehand — well, the closing was a shock, but it wasn’t a surprise. Did you feel the same way about the Arab League boycott of The Attack?

ZD: You found the exact words to describe it. In fact, I’m going to start quoting your words. Because, you’re right: I was not surprised at all. I was angry, actually. Because even if you are anticipating a negative reaction from the Arab world, as an artist, you’re still kind of hoping that somebody in the governments, some of those politicians are going to come along and surprise you in a positive way. I mean, we understand the Arab Leaguers, how pathetic they are. But maybe there’s somebody sitting in the ministry of culture who’s going to come out and say something else. And I was hoping that that would happen.

"I mean, we understand the Arab Leaguers, how pathetic they are. But maybe there’s somebody sitting in the ministry of culture who’s going to come out and say something else."

But then the expected happened. Some organization in Lebanon, called The Israel Boycott Committee, they went out and started campaigning: “How can you allow a film that has Jewish actors in it to be released in the Arab world?” So they contacted the Arab League, and they said, “Oh, yeah. We cannot let a film like this be in the Arab world, because we will be doing the Israelis a favor. Because the film is not anti-Israeli.” Maybe if the film were anti-Israeli, it would have passed very quickly.

But this is the way the world is, you know. I tried to fight with them, and tried to argue with them. I went on national television. But it simply didn’t work.

CM: Of course, the irony is, thanks to ban, the Arab League may have only created more of a market for bootleg DVDs of The Attack.

ZD: [Laughs] Actually, I went on Skype today, and I spoke to a friend of mine in Beirut. A shady guy that I actually like a lot, because he’s a childhood friend. And I asked, “Could you go to one of those bootleg DVD retailers and see if The Attack is out?” And he said, “I did go, before you asked me. And it’s not out yet — but I think it’ll be out pretty soon.” So I’m keeping track of this thing.

In fact, I asked him, “Look, it’s going to be bootlegged anyway, right? What if we sell it ourselves as a bootleg?” And he said, “A bootleg DVD in Lebanon costs a dollar. I can print you 10 copies — but I can’t promise you that there won’t be 10,000 other copes from which we won’t receive any benefit. Because anyone can buy one copy, and make a thousand copies out of it. So, financially speaking, it’s not a good investment.

“However, if you just want to fuck with the government, and defy them and release it, I’d be happy to do it . . ."