Christmas is just around the corner, which means you can either crack down on the Christmas shopping or take in a few entertaining events before the relatives, the weather, and Mariah Carey takes priority in the next couple of weeks.

We have a very eclectic lineup of stuff going on this weekend: a Theatre Under the Stars production of a chilly Disney favorite; an arena polo championship; the return of an ‘80s superstar; the grand opening of a new pickleball club; and two barbecue pop-ups that’ll have you sucking the sauce out of your fingernails.

Thursday, December 12

4th Wall Theatre Company presents Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike

Vanya and Sonia, two middle-aged siblings begrudgingly named after Chekhov characters, are living an uneventful life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The days are filled with predictable routines until their movie-star sister Masha arrives, accompanied by Spike, her charming (and incredibly attractive) young lover. Suddenly, their dull existence is turned upside down as old tensions resurface, leading to a weekend of uproarious chaos, unexpected romance, and unforgettable moments. Through Saturday, December 21. 7:30 pm (2 pm Sunday).

Asia Society Texas Center presents Mei Rui: "Your Brain on Beethoven"

Asia Society Texas Center will celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven's birthday with an innovative concert experiment. Award-winning concert pianist Dr. Mei Rui will present live performances of Beethoven's iconic masterworks, including the “Archduke” Trio, alongside state-of-the-art Brain-Computer Interface and EEG brain dynamics data visualization revealing how the performances impact musicians' and audience members' brains. 7:30 pm.

Theatre Under the Stars presents Disney's Frozen

Enter the icy world of Arendelle, where the newly crowned Queen Elsa has accidentally set off an eternal winter. Younger sister Anna, along with Kristoff, Olaf, and Sven, sets off on a snowy adventure to find Elsa and save the kingdom. Frozen features the songs you know and love from the Oscar-winning film, plus an expanded score with a dozen new numbers by the film’s songwriters, Oscar winner Kristen Anderson-Lopez and EGOT winner Robert Lopez. Through Sunday, December 29. 7:30 pm (8 pm Friday; 2 & 8 pm Saturday; 2 & 7:30 pm Sunday).

Friday, December 13

U.S. Open Arena Polo Championship

The 2024 U.S. Open Arena Polo Championship and USPA United States Arena Handicap come to Texas for the first time. Nine teams will vie for the national championship titles and the combined $70,000 in prize money. Arena polo, compared to hockey on horseback, is a fast-paced sport where teams of three players and their mounts demonstrate their prowess and agility. Spectators are up-close to the action — hearing players communicate and feeling the thunder of hooves. 12:30 pm (2 pm Sunday).

Improv Houston presents Brian Simpson

Brian Simpson is an Austin-based stand-up comedian based in Los Angeles. His background as a foster child and Marine Corps veteran has led to a rare combination of life experiences that he manages to channel into a refreshingly unique point of view. After landing a half-hour comedy special on Netflix’s third season of The Standups, Simpson returned to the streamer earlier this year with the hour-long, shot-in-Austin special Brian Simpson: Live from the Mothership. 7:30 & 9:45 pm (7 & 9:30 pm Saturday).

Derek Hough: Dance for the Holidays

Derek Hough: Dance for the Holidays is a celebration of the most festive time of the year. Fans will get to see Hough and his cast of dancers bring holiday tunes to life through dance, from the well-sung classics to modern pop hits. Creative team and Emmy winners Napoleon and Tabitha Dumo, also known as NappyTabs (Jennifer Lopez’s All I Have, Michael Jackson: The Immortal World Tour, GRAMMYs®), will co-create, direct, and supervise choreography for the tour. 8 pm.

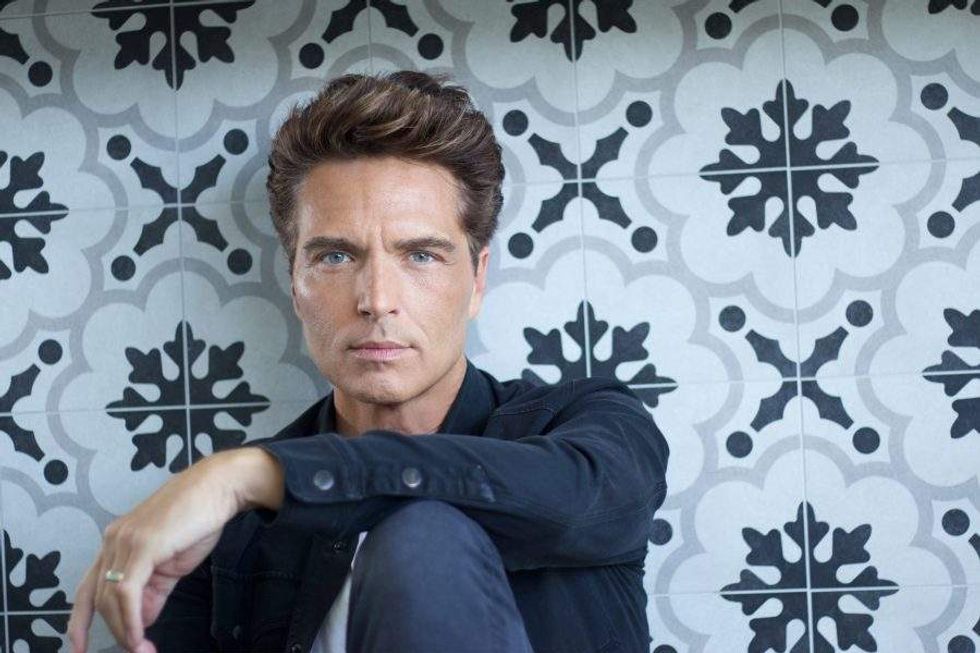

Richard Marx in concert

Man, Richard Marx was quite the ‘80s pop-rock troubadour, hitting us with such Reagan-era ditties as “Don’t Mean Nothing,” “Should’ve Known Better,” “Endless Summer Nights,” and “Satisfied.” (He had some cool ‘90s bops as well, including “Keep Coming Back” with Luther Vandross on background vocals.) The man who put a ring on MTV VJ/legendary ‘90s crush Daisy Fuentes will be performing those, as well as tunes from his many albums (including his latest, 2022’s Songwriter), in Sugar Land this weekend.

Saturday, November 14

Casa Pickle Grand Opening

Membership-based indoor pickleball club Casa Pickle will have its grand opening this weekend. The celebration will serve as a chance for the public to experience the club, which will be exclusive to members following the opening. Guests can enjoy sips, bites, tours, and competitive play. They can also tour the 20,000-square-foot facility, relax in the lounge area, grab a drink at the bar, or engage in Open Play pickleball on one of the nine state-of-the-art, PPA-certified CushionX courts. You can sign up for Open Play here. 6 am.

Axelrad presents KG BBQ

As we reported earlier this week, you can get barbecue this weekend from two spots that earned Bib Gourmand status in the Michelin Guide. First up, it’s Austin’s very own KG BBQ, which will have a pop-up at Midtown beer house Axelrad. The menu will include many of KG’s most popular dishes, including brisket rice bowls with smoked Mediterranean rice; smoked lamb chops; sumac-and-cinnamon-rubbed lamb shoulder, and sides such as pink buttermilk potato salad and Baladi salad. 11 am.

Stages presents Have a Nice Day Holiday Market

Join Stages for a night market of incredible food and craft vendors, music from Los Angeles DJ Lonny, lights, photo booths, karaoke and holiday filled fun for all. Vendors will include CultureMap Tastemaker Awards Pastry Chef of the Year winner Christina Au, Asteroid Coffee, Dumpling Haus, Boo’s Burger, Moe’s Vegan Bites, Elisa’s Homemade Crochet, and many more. You can also make it a day with a holiday show. Use code “NightMKT24” at checkout for 25 percent off their family friendly, fun-filled Panto Pinocchio. 4 pm.

Dawes in concert with Winnetka Bowling League

LA folk rock band Dawes, which now consists of brothers Taylor and Griffin Goldsmith (two bandmates departed last year), will be in Houston this weekend, playing music from their recently-released album Oh Brother. The new work steers Dawes decidedly forward, honoring 15 years of Taylor and Griffin’s musical relationship, as well as the next era of their band. They'll be joined by Winnetka Bowling League. 7 pm.

Sunday, December 15

Rosemeyer Bar-B-Q presents Whole Hogmas

Here’s the other barbecue spot that got the Michelin shout-out. Coming straight outta Spring, Rosemeyer Bar-B-Q will have a special menu of dishes made with smoked whole hog. The menu will include whole hog plates, whole hog sandwiches, whole hog-and-parmesan polenta cakes, and whole hog served over cheese grits with a New Orleans-style barbecue sauce, as well as sides and desserts. It’s all to raise money for Hogs for the Cause, an annual event that raises money for pediatric brain cancer research and the families who are fighting it. 11 am.

Blippi: Join the Band Tour

If you have one of those iPad-carrying tykes who love the kiddie programming that comes outta YouTube, you can watch them lose their minds when one of those YouTubers appears in the flesh. Blippi comes to Houston as part of his Join the Band tour. Blippi will be joined onstage by Meekah, their singing and dancing buddies and live musicians to explore what makes music, including sounds, rhythms, and instruments, through all of Blippi’s favorite hits. 2 pm.

Alamo Drafthouse LaCenterra presents Gremlins Movie Party

Joe Dante’s iconic holiday misadventure from 1984 continues to be a pop culture sensation, with its darkly funny story of a small-town guy who receives a furry little creature called a mogwai that ends up multiplying into a swarm of monsters that rip the town to shreds. You won’t be able to tear the place apart or ruin the theater’s electronics, but they will have all kinds of fun props available to help you get in on the action. 6 pm.

Photo by Melissa Taylor

Theatre Under the Stars presents their new vision for Disney's Frozen.