Show me the money

Business incubator: Bayou City Art Fest says no more starving artists, debuts innovative program

For visitors who stroll the grounds of Memorial Park during the Bayou City Art Festival, the three-day affair that runs through Sunday feels like a colorful shopping bacchanal offering fresh creations by more than 300 artists working in 18 different genres.

But those close to the Art Colony Association, which produces the event, are aware that beyond being a revenue-generating opportunity for artists, BCAF is a conduit that supports other charitable endeavors. The festival has made contributions upwards of $2.7 million to its nonprofit partners since its inception. But its leadership isn't stopping there.

A new category aimed at nurturing new festival talent debuts this year.

The Rising Talent category hopes to zap the steep barrier of entry for artists that want to be in the show but have little know-how of the inner workings of large, juried arts festivals. Daunting questions of accessibility, affordability, marketing and risk management — subjects seldom taught in traditional fine arts schools — turn ambitious reveries into haunting nightmares. Most throw their hands up and give up.

"This year, it's time we step forward," Kelly L. Kindred, BCAF executive director, says. "We are hoping to identify new artists in the industry and give them a forum where they feel welcome and supported. We want to be an arts incubator of sorts and mentor talent through the process."

Kindred, who rose to the leadership position in 2011 after former executive director Kim Stoilis was hired as president and CEO of The Houston Festival Foundation, the group that hosts iFest, opted for a slow-and-steady strategy to optimize the program. First, she focused on keeping established operations running smoothly before introducing new plans. Now, she says it's her duty as an art supporter to be an advocate for the growth of the next generation that will contribute to the creative economy.

"There's a concern in the art festival industry about the graying of regularly touring festival artists," Kindred explains. "There's not much new talent coming in — and that's a shame because many could do really, really well in a show like this."

The program subsidizes part of the booth fee and underwrites the cost of the tent. In addition, a seasoned festival mentor will help Rising Talent entrants and empower them with tried and true techniques to manage their art business.

"In the art world, if you aren't already well-known and represented by major galleries, it's very hard to get out there and make any money with your art."

"One of the unique selling propositions of the festival is that artists are available at their booth at all times," Kindred says. "Teaching them how to interact with the public is so important. That interaction can turn casual passersby into prospects and into sales."

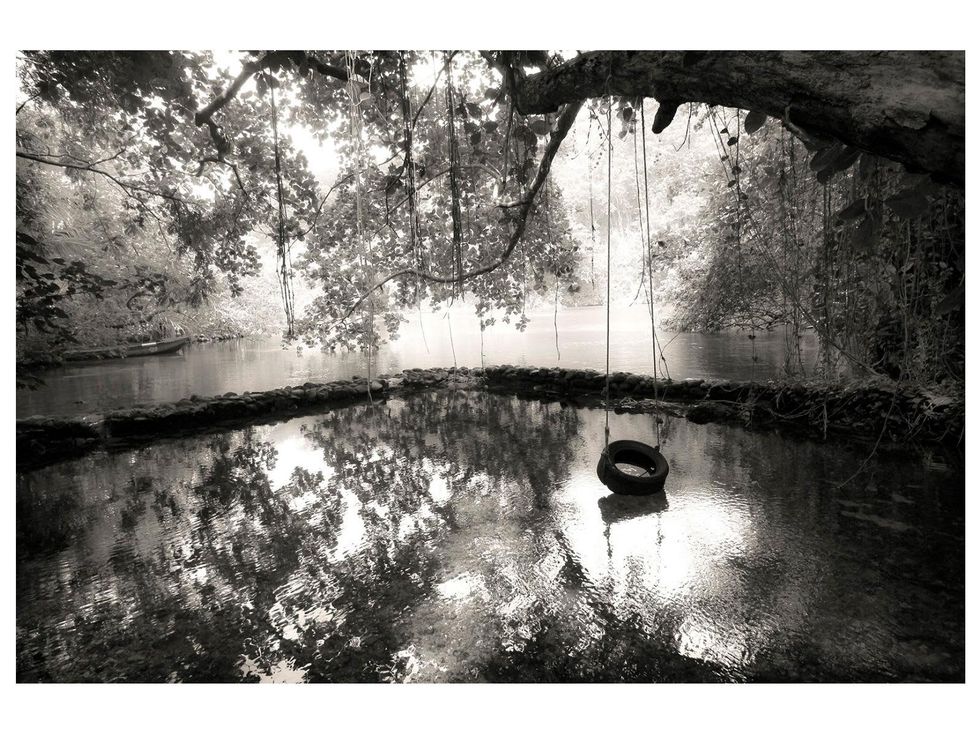

Acceptance into the program means Galveston-based photographer Amanda Schilling will be able to participate in her first festival. She says that artists often have to work two or three jobs to support their craft. While she has been recognized in several national and international exhibitions — surely a confidence booster — selling work isn't guaranteed.

"The term 'starving artist' exists for a reason," Schilling tells CultureMap. "In the art world, if you aren't already well-known and represented by major galleries, it's very hard to get out there and make any money with your art."

Schilling is aware that the work needs to be of fine art quality but also have wider appeal.

"Some artists may see participation in festivals as a kind of sell-out because of the need to appeal to the masses, but if you are truly trying to make a living as an artist, it's important to not only do work for yourself, but also to make work that people want to buy and live with in their homes," she says. "It can be a fine line."

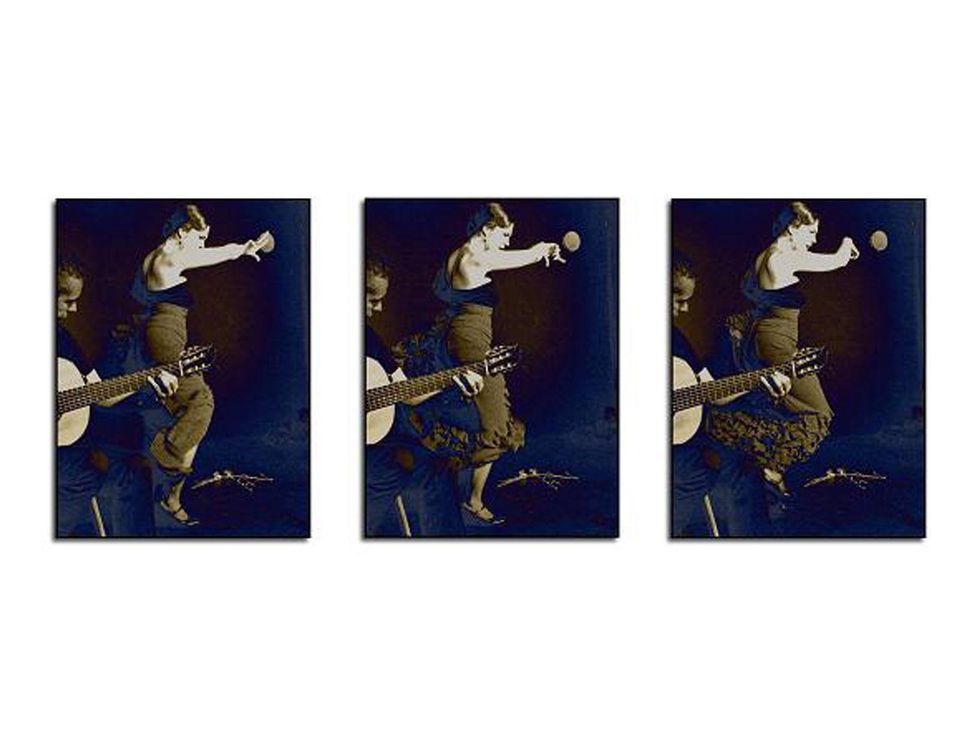

Houston-native Alejandra Fabris, also a Rising Talent at BCAF, believes that festivals harbor the most potential for establishing an artist's income by setting pricing benchmarks.

"A festival puts an artist on the map because it is an excellent venue for cultivating public interest in a new particular line of work."

"Even if what an artist does is beautiful or truthful or innovative, I can't see how it would be feasible to put a price tag on any given artwork if no one else knows of its existence," Fabris explains. "A festival puts an artist on the map because it is an excellent venue for cultivating public interest in a new particular line of work."

There's no question that large festivals also foster a kind of competitive edge between participants. As such, her objective is to stay close to her interests, genuine to her voice and and honest to her heart.

"I still believe that most people will recognize artistic integrity when they see it and that, as bizarre as it might sound, I think integrity sells," Fabris explains, joking that, following the advice of an experienced colleague, when one enters the "circus" one has to be the funniest, most engaging clown.

Out of 15 applications received, the inaugural class of the Rising Talent category also comprises jeweler Aleksandar Bozhkov from Santa Monica, Calif., Conroe-based ceramicist Jennifer Claussen, Fort Worth sculptor Gerhardt Wissler and mixed-media, collage artist Grant Manier, whose submissions were juried blindly alongside the rest of the entrants.

Kindred kept the number of Rising Talent artists small to test the efficacy of the curriculum and tweak components prior to broadcasting a more visible call for submissions. She plans to publicize the program through platforms like Fresh Arts and Glasstire for the next Bayou City Art Festival Downtown.