A Presidential Turn

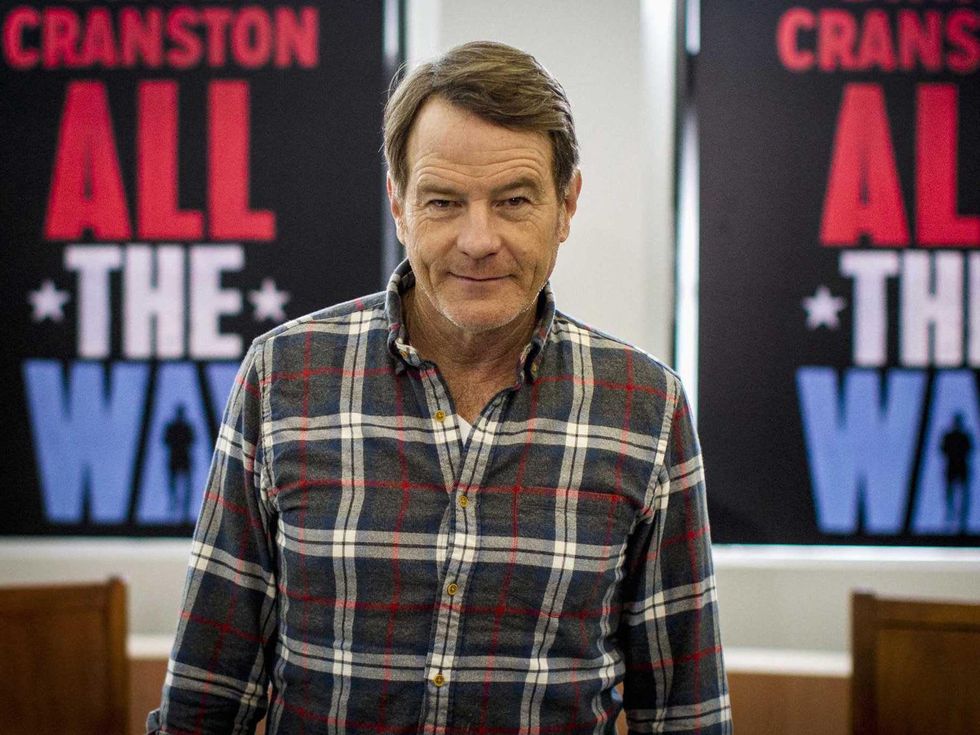

Breaking Bad star takes on Broadway, pot & prostitution: Why Bryan Cranston would legalize everything

NEW YORK — Don’t vote for Bryan Cranston. For anything.

"I’m not electable,” he insists. “The first thing I’d do is legalize prostitution and marijuana — even though I don’t partake in either. But I’m progressive. And that would take the budget completely out of the red and into the black. It would solve a tremendous amount of problems.”

Then he smiles and shrugs his shoulders as if to say, “See? Toldya so.”

He may be underestimating his appeal. And his way around a filibuster.

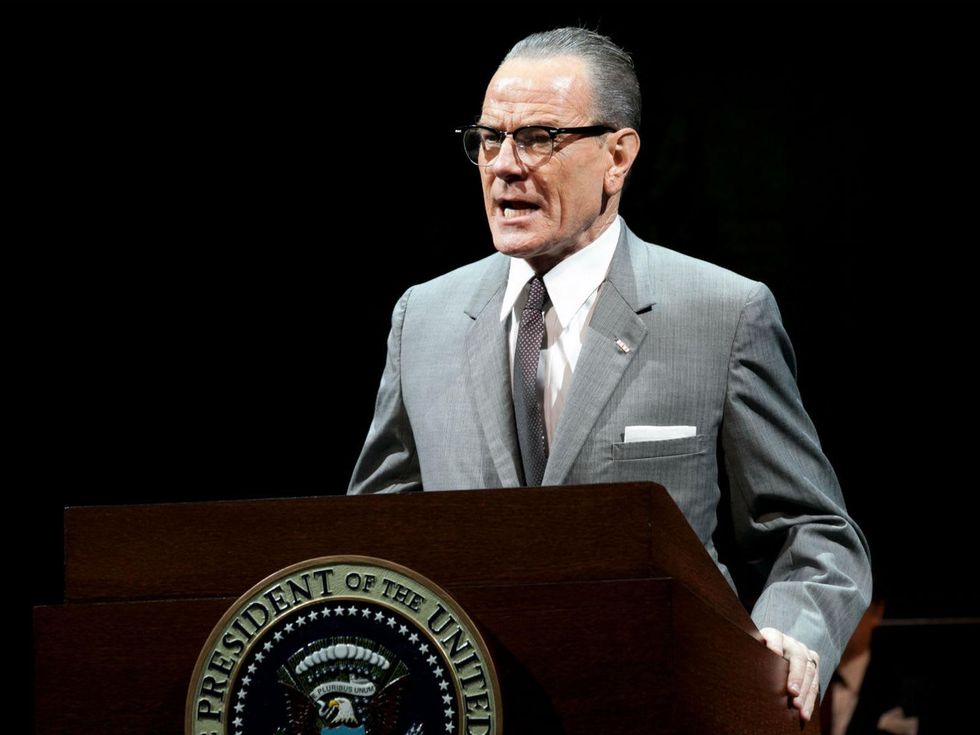

Both are apparent now that Cranston — the Emmy-Award winner who sunk to deliciously depraved lows as chem-teacher-turned-meth-dealer Walter White in TV’s Breaking Bad — is playing LBJ.

Yep, that’s his new gig, bringing to life — on Broadway — the obstreperous, dust-kickin’, big-dream dreamin’ Texan Lyndon Baines Johnson, in All the Way, a new play by Robert Schenkkan (also a Texas native — and a Pulitzer Prize winner). It opened at the Neil Simon Theatre in Manhattan last week to great reviews.

“The first thing I’d do is legalize prostitution and marijuana — even though I don’t partake in either. But I’m progressive. And that would take the budget completely out of the red."

Seem a stretch? Those used to seeing Cranston as the whacked-out White may find some odd similarities between the two roles. Both figures are fueled by enormous stores of inner resolve. Both forge unexpected paths abiding inner compasses all their own. And their jobs? Messy, requiring a poker face, strong stomach and the willingness “to get your hands wet,” as Johnson says onstage.

They’re also masters at hiding their true personalities.

"He was a gregarious, back-slapping good-ole-boy,” says Cranston of our 36th President, “not the buttoned-down, measured person he presented to the public. He did that because he thought it was more presidential.”

The play looks at one seminal year, from November 1963 (when veep Johnson ascended to the Presidency after John F. Kennedy’s assassination), to November 1964 (the date of the next Presidential election). Fearing he might not win, Johnson realizes he has only one year guaranteed in the Oval Office, and chooses to make the most of it, pushing Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act, one of the most significant — and controversial — pieces of legislation in U.S. history.

Getting this play produced seems as implausible as that legislation. Just try floating this idea to theater producers — OK, it’s a new play no one’s heard of, it’s historical and requires 24 actors. Mmm, good luck with that.

Such is the weight and revving power of Cranston’s name right now that this production got anywhere near Broadway.

"I got cast before I knew the Lyndon,” says Betsy Aidem, who plays first lady Lady Bird Johnson. When she heard it was Cranston, she thought, “Oh, this is a game-changer.”

"Cranston’s got the stuff, he’s got the juice,” agrees Michael McKean, who plays J. Edgar Hoover.

Exploring the Hill Country

Part of what drew Cranston to the role, he says, is the playwright, who seemed to have an inside scoop on the outsized Texan. Schenkkan says to know LBJ, you’ve got to know the Texas hill country from whence he came.

"My Texas bona fides are genuine,” notes Schenkkan, who moved to Texas when he was 2, grew up in Austin and attended the University of Texas.

Part of what drew Cranston to the role, he says, is the playwright, who seemed to have an inside scoop on the outsized Texan.

To research his play, Schenkkan visited the LBJ ranch (home of the “Texas White House,” about an hour west of Austin) and the LBJ Presidential Library (in Austin), meeting with director Mark K. Updegrove, plus former directors Harry Middleton (who also served in the Johnson administration) and Betty Sue Flowers; Joseph A. Califano Jr. (a top LBJ White House aide who later became Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under President Jimmy Carter); and most of the Johnson family..

"There’s not much these folks agree on, except that “he changed everybody’s life,” Schenkkan says. “There’s nobody who knew him who doesn’t seem to feel changed by the experience. Altered. For. Ever.”

If Johnson shaped lives, what shaped his own seems to be the hill country where he grew up — at first prosperous, the son of a successful rancher and politician, then poor, after his father lost it all, Schenkkan explains, and Johnson experienced firsthand poverty and shame.

“The hill country is beautiful, but it’s a hard place to grow up, especially during the depression and before electricity,” he says.

Both Cranston and Aidem traveled to the area to tour LBJ’s ranch.

“There’s something about the hill country, your whole nervous system goes into a calmer place,” says Aidem, who also explored the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin.

So what sticks with them about the ranch? First and foremost, the three television sets, which ran constantly back in the day, tuned to each of the then three major networks.

Cranston spotted embroidered pillows in Lady Bird’s bedroom — one that read “I slept and dreamt of a life in beauty;” another, “I awoke and found a life of duty.”

Good luck snagging a carefree nap on one of those.

For Aidem, it was Lady Bird’s bathroom that intrigued, particularly a mirror, placed high at a tilt. She couldn’t imagine what it was used for.

Well, look in the mirror — what do you see?” her tour guide beckoned.

Aidem saw the back of her head.

"When you have a bouffant,” the guide explained, “you don’t want to have any holes in it.”

Welcome to 1964

Cranston, raised in Canoga Park, Calif., was a kid when the play takes place, but he recalls how the period shocked and politicized the adults around him. He can still picture his 8-year-old self noticing that “something was up and that I should start paying attention,” he says. For him, Johnson was “the first president I became interested in.”

Talk to any of the actors in the play (most of whom play multiple roles) and you’ll hear that the chance to play real-life figures from such a tumultuous period is what attracted them to this production. This is especially true for Cranston, who must embody the immense contradictions of Johnson — a man who fought for civil rights in one breath, then tossed around the “N” word in the next.

But that’s what makes him fascinating, notes Cranston, who knows a thing or two about complicated characters.

“He had tremendous goals — he wanted to accomplish something,” says Cranston. “He said” — and here Cranston slips into his twangier, gruffer LBJ voice — “ ’What the hell’s the point of being President if you can’t do what’s right?’ ”

What to say of LBJ?

Historians love Lyndon Johnson’s contradictions — from biographers Michael Beschloss and Doris Kearns Goodwin to Robert Caro, whose LBJ books span 3,388 pages (and he’s not done). But they don’t all agree on why, in the face of incredible odds — and during an election year — Johnson chose to push the Civil Rights Act through Congress.

For playwright Schenkkan, the answer lies in one of Johnson’s earliest jobs — as a first-grade teacher to dirt-poor Mexican American kids from a border town in Texas. (Just imagine him, all six-foot-four, looming over them.)

Johnson loved his students and their eagerness to learn, Schenkkan explains.

“Yet there would be this moment when he’d see the light in their eyes die because they realized the world hated them because of the color of their skin,” Schenkkan says. “It’s the moment they realized they were other, and less than, because of racism. That clearly resonated with him in a profound way.”

Some historians suggest Johnson’s support of civil rights was political expediency, but Schenkkan thinks otherwise.

“He’d experienced poverty, he’d known ‘other’ and he’d seen how wasteful, how crushing, how ugly racism could be,” Schenkkan says. “No, this is a man who walked his talk. He lived it. It mattered.”