Looking Back: A Murder in Montrose

A murder in Montrose: Gay-bashing death of Paul Broussard is re-examined in new documentary

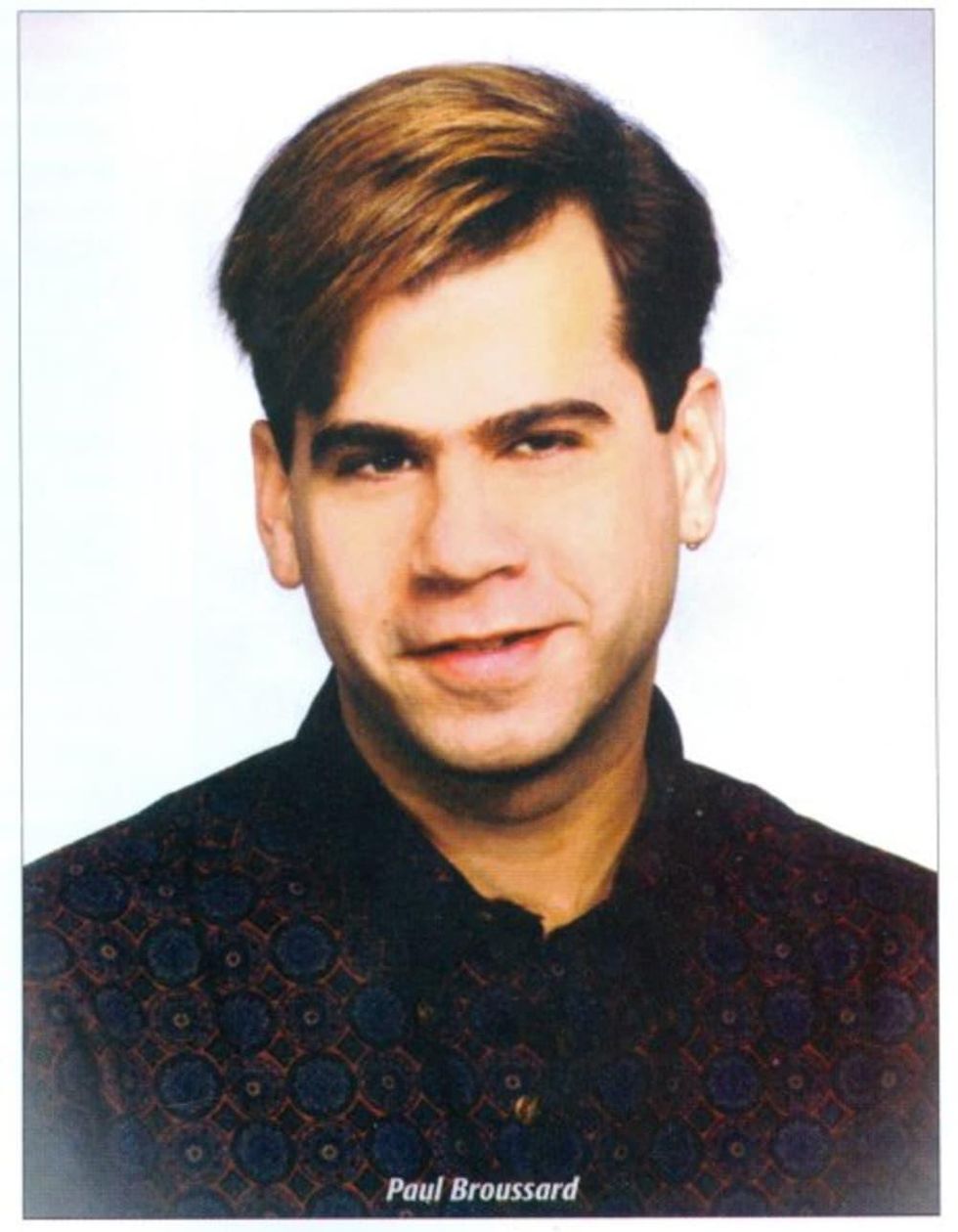

Twenty-five years ago, the untimely death of Paul Broussard at the hands of a group of Woodlands-area youths catalyzed an unlikely alliance at the time: Members of the gay and straight communities in the Houston area decided this murder, and the response (or relative lack thereof) from law enforcement and medical personnel, was unacceptable.

Eventually "The Woodlands Ten," as they were known, would be convicted; but first, our city and the nation took a hard look at discrimination and the fallout from bigotry.

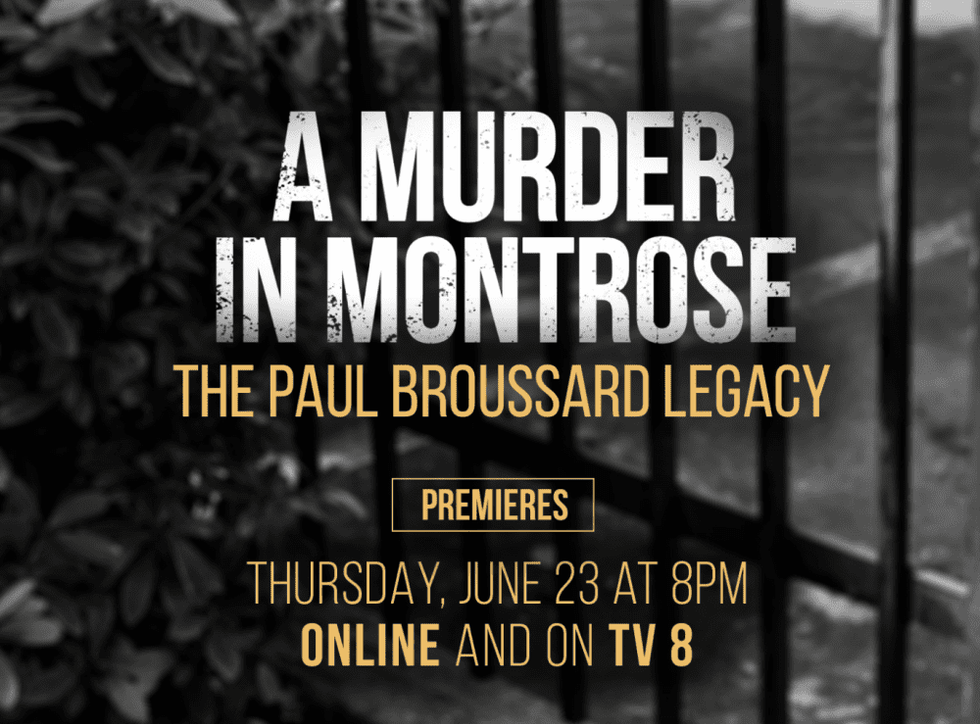

Now, in the wake of the Orlando Pulse Nightclub massacre, Houston Public Media TV 8 is airing A Murder in Montrose: The Paul Broussard Legacy, a documentary that examines the aftermath of the Broussard killing, and how the community has evolved since. Before the documentary premieres (Thursday, 8 pm), we sat down with with Ernie Manouse and Matt Brawley, who helped produce the documentary, at HPM studios to talk about how attitudes have evolved since that point in 1991, and how the communities are moving forward.

CultureMap: When did you start this project?

Ernie Manouse: Actually about a year ago. I think a lot of people out there will think that we did this in reaction to what happened last week (in Orlando), but actually this has been many months in the making. It’s just a sad coincidence that we have this program when something like this happened.

CM: A lot of elements of social injustice led to the death of Mr. Broussard; from the amount of time it took for EMS to get him to a hospital to finding a doctor to treat him. Can you talk about that?

EM: Regardless of what happened in that moment, what we found fascinating was the community’s reaction to it. The community was already upset. There was already tension building. They were upset with the police, they were upset with the way things were being handled by the city. It was a hot summer; there was a mayor’s race. All these things were happening and somebody gets killed. And the community lost it, basically. They were going to find justice, and they were going to move the cause forward.

There was a rally that shut down Westheimer and Montrose. That rally got national attention. National attention led to change in the way the police viewed the (gay) population, and change in legislation in the state House, eventually. It all came out of this moment. So regardless of what actually caused the death, how it happened, who did it, why they did it, it was that a man died, and a community reacted. And that’s kind of the story we’re telling.

CM: So you would describe this as a pivotal point for the city?

EM: It was a moment where not just the gay community became upset and came together to rally; it was all communities that got upset and came together to rally. That’s what made it so important to us — the fact that it was no longer just a gay crime. There was a unity there. For the first time gays and straights came to together to say, Enough is enough. And that made it a much bigger story.

And it’s kind of like what we see in Orlando today – that’s part of the change you notice in the 25 years between these two incidents. When this happened, Paul Broussard was a gay man who got killed, and people got upset and it got attention because all communities came together. This time it was 49 people who were killed, regardless of what their sexual orientation was, and everyone was expected to be outraged because we are all one now. So I can see the growth there. Nobody says, 'Can you believe straights and gays were picketing together because they’re upset what happened in Orlando?' Nobody says that. It’s accepted now. And that’s the growth we’ve made. It’s a crime against all of us now. In a weird way, that’s a good thing – we all support each other now.

CM: Do you remember where you were when Paul Broussard was murdered?

EM: I was in Chicago at that time, and I remember there being incidents of hate crime, even though we didn’t term it that way back then – fag bashing, gay bashing. And one time I was walking home from a bar around the same time – late '80s, early '90s, never concerned about stuff like that, never worried, and then a group of guys drove by in a car, and someone yelled out the window, ‘Fag!’ And I always thought, How could that hurt you? It sounds so stupid – but I remember being shaken up about it, you know? And walking the rest of the way home thinking, Wow that really upset me.

To say it was unique to Houston at that moment would be a lie. It was happening in every major city. It was happening anywhere you could find a group of people to attack. In some way, it was almost seen as acceptable. At that time some people thought that was fine. You look at some of the rhetoric that’s happening today around politics, and you hear the things they say, you step back and you think, What makes them think it’s okay to say that? It’s the support around them that agrees with it. These ideas aren’t that far away. They shift from community to community who’s okay to pick on at any given time, but we seem to have something within us that makes us okay with tormenting the less fortunate, the less populous.

CM: Houston is a pretty progressive city, even in 1991 – and it’s notable that the people who perpetrated this act drove down from The Woodlands. Do you have any thoughts about how we can be in an urban nexus of diversity and understanding, but our ex-urban areas might not be as open-minded?

EM: Annise Parker addresses it in our documentary. A lot of rhetoric came out at the the time about it being people from The Woodlands, but her view is it could have been from anywhere. Any small town. It was pack mentality. Teenage boys, this surge of adrenaline and hormones, and it was a time when fag jokes were on the radio, it was kind of seen as okay to make fun. It was very much a minority community that could be picked on ... it was almost like sport. It was the culture. It’s hard to believe that’s so close to where we are today, time-wise.

CM: I feel like the farther we get from the center of the city, the harder it is to find the sympathy that may be needed.

EM: It’s interesting that at the time, I think, because more people were coming out. Someone mentioned in our documentary, AIDS kind of forced a lot of people out of the closet. When you’re in the inner city, you get exposed to more. It’s very hard to hate someone you know. It’s easy to hate someone you don’t know. So when you’re in an urban setting in a major metropolitan area, you hope that people know other people and there’s kind of a community that evolves. And as you get further out, there’s less exposure to it, less understanding maybe – and that’s just armchair speculation.

CM: In 25 years a lot has changed with regard to the support surrounding the gay community, and I would say that the number of members of that community has grown because people aren’t as afraid of identifying in that way. Do you think technology has played a role in that growth? Say, with the internet, and the chance for everyone to share ideas more freely?

EM: I think it’s as simple as even the TV show Will and Grace. That show comes on the air, and everyone is freaking out initially about it, and yet what it did is it brought likeable gay characters into the home of everyone in America, and they no longer became threatening. And if you didn’t have that kind of technology, you couldn’t have gotten that. Now, zip forward with the internet, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram – you continue to live your life there, and people see it.

There’s an interesting point when we talk about HERO (Houston Equal Rights Ordinance) – that war has already been won, because the younger generation – it’s fine to them. They have an easy understanding of it. The problem is these battles we’re fighting along the way are not being won because the people who vote, the older generation, is much more set in their ways. Thirty years from now, it’s probably going to be a non-issue. And that’s how things are changing and evolving.

So it’s interesting – there’s a point that’s brought out in the documentary, too – the fact that there were almost 2,000 people at this rally at Montrose and Westheimer two weeks after Paul’s death, makes it amazing by those standards when they didn’t have the internet. The way they did it was phone trees. You heard, you told 10 people, and you told them to tell 10 people. And that’s how it had to spread. Today you can get on the internet and in two minutes, have 20,000 people knowing about something. Technology changes all that. I mean look at the rallies that happened around Orlando in our city. There were rallies on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday — and all of them were heavily attended because they got the word out that way.

CM: Right, Facebook!

EM: People like to tear on it, but it's a good way to stay connected.

Matt Brawley: I liked that last question (about technology spreading alternate views) just because I come from a different perspective than Ernie comes from as a straight man. And actually, I moved here less than a year after this happened, so I knew nothing about it until Ernie pitched this show idea, and it’s been a learning process for me. I grew up on military bases, and I think Ernie might be the first person that I ever knew who was openly gay. And I met him when I was 21 or 22. I do think the key to moving past this type of stuff is exposure — exposure to people who are different from you.

I was never someone who would’ve leaned out a car and yelled at somebody, but I certainly grew up in environments where if you wanted to put someone down, that was the quickest and easiest way to do it, was to call them a fag or make that implication somehow. And I’m sure that’s probably an experience for a lot of people my age, who grew up in the 80s and 90s, that was very common.

EM: My best friend in high school used to use the word 'fag,' and he would turn to me and say, ‘Oh, but you know how I mean it,’ and I’m like, that’s nice of you, at least … (laughs)

MB: I’ve been in Houston since 1991, and we talked about the city being progressive – I mean, I think it’s had a profound impact on who I am as a person, and how I view the world; and I wonder – people who don’t have that sort of exposure, how different their viewpoint is, and I think you see it manifest itself in a lot of different ways. Hopefully a project like this can help in that regard and give that exposure to some people who haven’t seen everything there is to see, and haven’t met everyone there is to meet. That’s what’s been motivating me to really work hard on this. I think this show can do a lot of good.

-----------------

A Murder in Montrose: The Paul Broussard Legacy will air on Houston Public Media TV 8 at 8 pm Thursday, June 23. A live screening at Houston Public Media will be followed by a live televised town hall discussion led by Ernie Manouse. As of this writing, the event is sold out, but people who wish to share their memories of the Paul Broussard murder can do so by visiting the HPM website.

Ernie Manouse, center, interviews Houstonians involved in the protest of the murder of Paul Broussard 25 years ago. The protest took place at the corner of Westheimer and Montrose.