Picturing The Parks

Mark Burns' amazing journey to photograph every national park in the U.S.

When photographer Mark Burns was growing up in Houston, he didn’t have many everyday opportunities to gaze upon great mountains and sweeping vistas, but that changed when his family went on vacations. In those family car trips to west Texas and Big Bend and then onto New Mexico or up into Colorado, Burns first began to understand the magnificence of this country’s vast landscapes.

Now years later, that appreciation found its ultimate expression in his photographic exhibition The National Parks Photography Project, on view at the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

I recently had a chance to speak with Burns about the exhibition and what set him off on this monumental quest to capture one defining image from each of the 59 U.S. national parks. The project began over five years ago after he created and produced the exhibit The Culture of Wine for the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum in College Station, when Jean Becker, Bush’s chief of staff, asked if he had ideas for another exhibition.

Even back in 2010, Burns was already thinking about a photographic way to commemorate the National Parks Service centennial anniversary in 2016. After an advisory committee was brought together and a “collaboration” with the Parks Service was made, Burns set off on his journey that would take him to every national park.

The Wild Trek

Though he began relatively close to home in the southwest, Burns eventually drove to all of the national parks in the lower 48 states in his Toyota FJ Cruiser, racking up about a 160,000 miles during his five-year odyssey. When driving wasn't an option, he left the Cruiser at home and flew to Hawaii, Alaska and America Samoa to complete the list.

“The third and fourth years I was really all over the place, traveling extensively,” Burns explained, describing his route that would take him nine or ten thousand miles in one trip. “Some of the trips that I did took me from Houston through New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, over to Montana and then back down through Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico to Houston.”

Many of the the parks he visited multiple times “chasing weather and also trying to be there during different seasons,” he said.

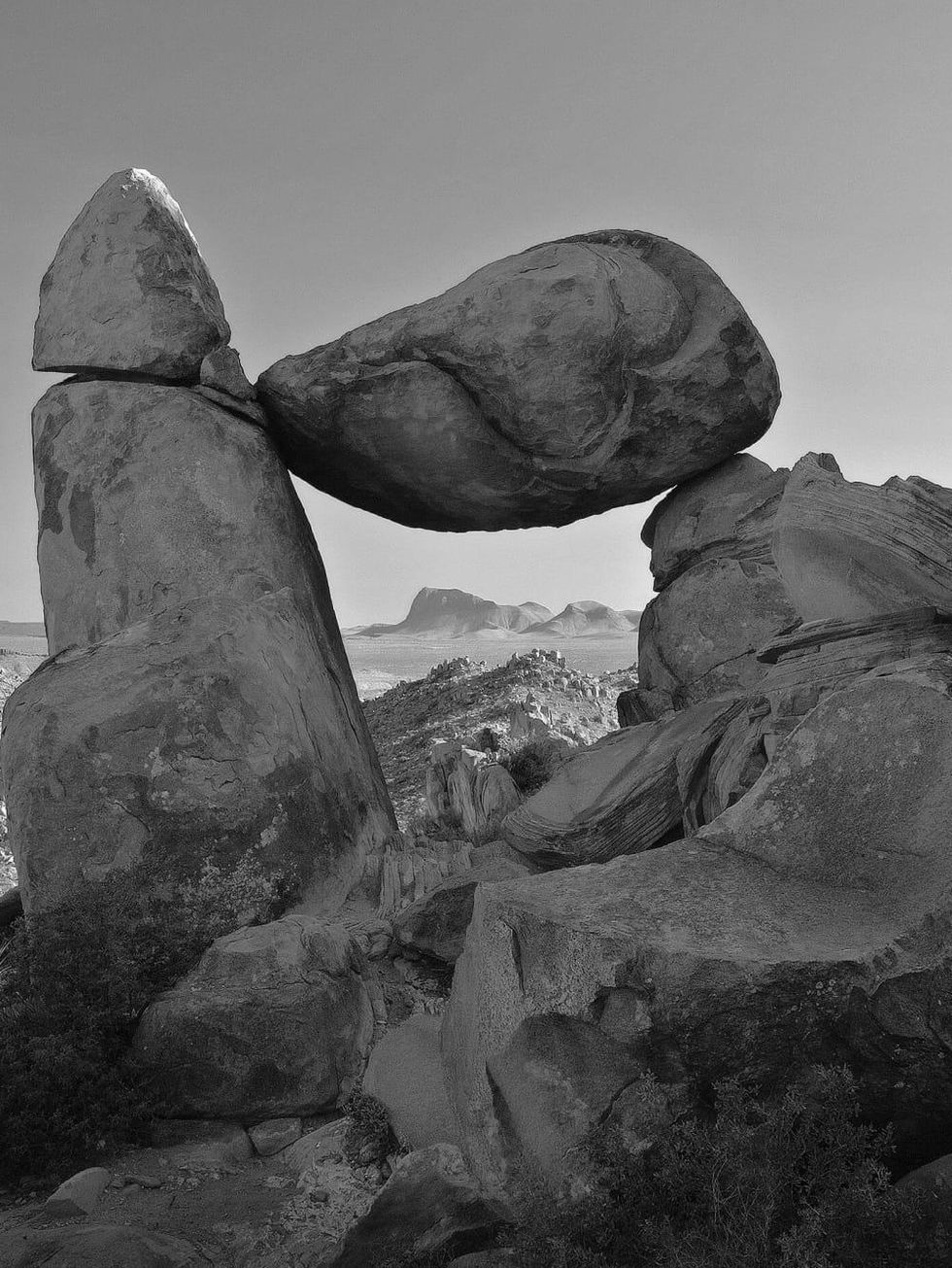

From the onset, Burns knew that he wanted to take black-and-white photos of the parks because he loves working in black and white for artistic reasons, but he also felt it the best type of photography that would link the parks in the 21st century back to the previous hundred years.

“Right from the beginning I made that connection in my mind that it would be a neat bridge to have people looking at photographs that would have a contemporary date, but they would be in black and white, and that would look similar to those [photos] of the 1910s, '20s and '30s,” Burns explained.

The Land and Sea Alone

Looking at this vast expanses frozen in time on paper, visitors to the exhibition might also notice that there are no people amid the mountains, rivers, glaciers, beaches and cliffs, as Burns made a decision early on not to include the “human element.” He did include a few human-made structures, like Proenneke’s Cabin in Lake Clark National Park Alaska, and the lighthouse at Biscayne National Park, but only if they were an important element of the landscape or represented the character of the park.

Burns also made a distinction between landscape and wildlife photography. The few animals captured in some of the photos, like brown bears in the Katmai National Park photo, are such a part of the topography of those parks that he felt they had to be included.

Burns also created a balance in the exhibition between iconic images probably known to most Americans and those places of wilderness yet to be overwhelmed by the vacationing crowds. For example, while he captured beautiful pictures of the Yellowstone River, he realized after he kept hearing “Where’s Old Faithful?” he knew his photo of the famous geyser would have to go in the exhibition.

Yet when I asked Burns if there was an underappreciated park he grew to admire, he became practically poetic in his descriptions of Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California, a park he had originally just wanted to check off his list but found himself revisiting several times just to see the change of seasons.

Texas Beginnings

While the The National Parks Photography Project might have officially began five years ago, it became apparent while talking to Burns that this was a journey that truly began with those family trips of his childhood.

“My dad would take my brother and I. For a period of about six or seven years we would go to into southwestern Colorado and New Mexico. That’s were I cut my teeth in landscape photography,” Burns said telling the tales of his first attempts at photographing the southwest. Instead of the usually whines of a kid asking if they were there yet, he would ask his dad to stop along the road so he could get a picture of some image that had caught his young photographer’s eye.

“We went to Big Bend some and I certainly enjoyed going out to west Texas and Big Bend because it was such a different environment from Houston. My eye started to see landscapes probably in that Big Bend area.”

Now Texans can take their own journey into the wilds of all our national parks with just a few steps into the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

The National Parks Photography Project is on display until September 28 at the Houston Museum of Natural Science.