Paint the Revolution

Revolutionary Mexican Modernism exhibition highlights exclusive Kahlo and Rivera paintings

For nearly two decades, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston has committed to presenting the greatest of Latin American art, so it’s too not surprising when the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City organized the exhibition Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950 that the MFAH wanted in on the art action.

“I couldn’t imagine this exhibition not coming to Texas, certainly not to our museum, given how strong and central the Latin American program is to our identity here in Houston,” explained MFAH director Gary Tinterow during a recent exhibition media preview.

Tinterow also remarked on the tremendous amount of work from all three institutions it took to add the MFAH to the short list of venues presenting these coveted works of art, but how important it was to do so, especially as Paint the Revolution becomes “the very first exhibition to focus exclusively on the contributions to the world art scene by Mexican artists in the first half of the 20th century.”

The exhibition brings together 175 works of paintings, prints, photographs, books, newspapers, and broadsheets from Mexico’s most celebrated artists of the 20th century — Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros — as well as some of their extraordinary contemporaries who might not be as well known to U.S. museum goers, including Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo), Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Miguel Covarrubias, Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Carlos Mérida, and Roberto Montenegro.

Along the way, the exhibition also showcases the dual visions of these Mexican but also Modernist artists.

“Innovative artists in Mexico had a least big two agenda points,” explained Matthew Affron, curator of Modern Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “One was to connect their work to what was most cutting edge in modern art in the Americas and in Europe. While at the same time, they wanted to root this international art in a sense of specificity about national Mexican traditions and cultures.”

Affron’s colleague, Renato González Mello, director of the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, added that these artists were “skilled at using ways and style of symbolist art” while depicting the revolutionary landscapes and social change of the times.

With a selection of art that spans 40 years, from the Mexican Revolution through decades of some of the artists working in the U.S. and abroad and then to the lead-up and aftermath of World War II, the exhibition includes many trends and themes that probably can’t be fully appreciated in just one visit. But for a first look, here is a quick guide to some exhibition highlights.

Houston Exclusives

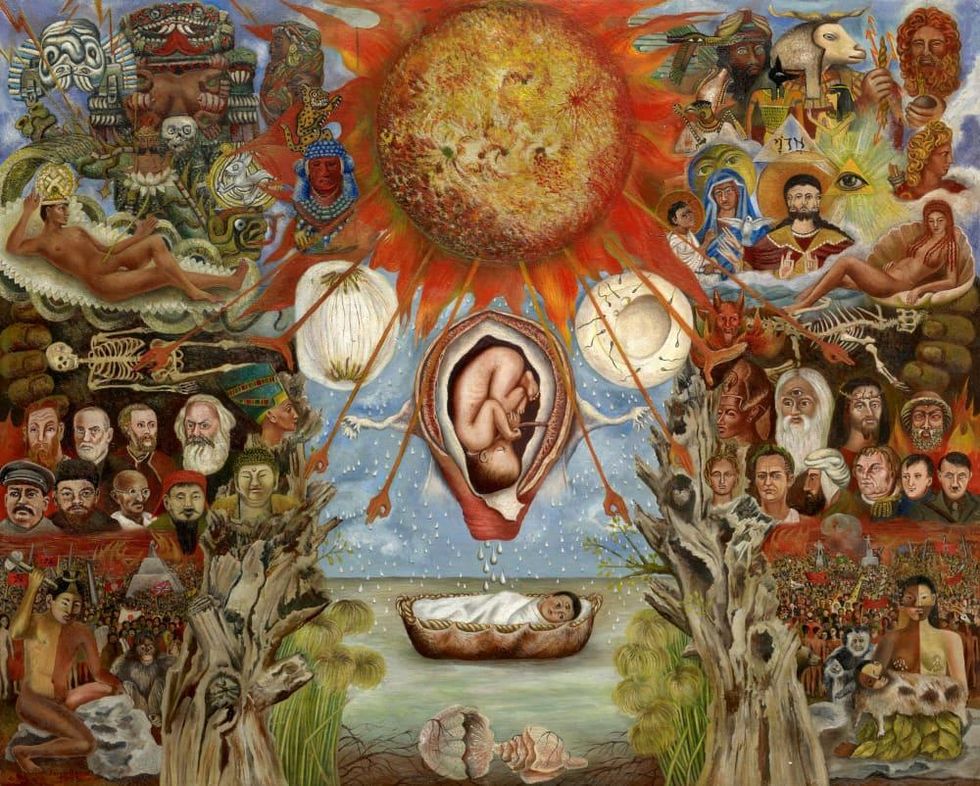

Among the artworks are several that can only be seen in the Houston leg of the exhibition’s tour, thanks to the MFAH adding pieces from their own collection and generous loans from Houston collectors. Don’t miss the dark and haunting Cara de niño (Concentration) by David Alfaro Siqueiros and three from Diego Rivera, including Cartoon for Liberation of the Peon and Still Life with Lemons from the MFAH and Self Portrait: The Ravages of Time from a private collection. It might be worth a second or third visit to the exhibition just to fully absorb and admire the vastness of imagery within another work loaned from a private local collection, Frida Kahlo’s Moses.

Modernism through a Mexican Perspective

The Modernist trends in art in the early 20th century — Impressionism, Symbolism, and Cubism — were certainly known and practiced by Mexican artists, but many were also concerned with bringing Mexican aesthetics and depicting images of Mexico in their works. Many of the works, especially in the first section of the exhibition, attest to the marrying of Modernist forms with Mexican and revolutionary content.

20th-Century Art Presented with 21st-Century Technology

Some of the greatest works of the period can’t physically be moved from the place of their creation, so Paint the Revolution does the next best thing in its center gallery by transporting, through simulation, the viewer to the art.

“The most famous and recognizable dimension of modern art in Mexico is mural painting, and mural painting in its most classic form is bonded onto the wall of public buildings and therefore immovable and only making sense in situ,” Affron explained.

The exhibition uses mural-sized digital projections to bring viewers to the Secretariat of Education in Mexico City to walk alongside Rivera’s Ballad of the Agrarian and Proletarian Revolution (1928–29) and to Hanover, New Hampshire, to study Orozco’s Epic of American Civilization (1939–40) amid the library reading room at Dartmouth College.

“We’ve been able to create an image that shows you the mural panels and the way they exist in architectural space and even brings you, in a sense, in a walk past them in time,” Affron said.

Painting the United States

After the Mexican Revolution, in the 1920s and 30s, many of these artists traveled to and worked within the United States and depicted the life and people they saw, but they also gained commissions and found wealthy American patrons.

“A very fascinating portion of the exhibition that is relevant to us here north of the border is how great Mexican artists agreed to work for U.S. capitalists like the Rockefellers and Henry Ford, even though those capitalists with their great corporate machines were the actual target of the Mexican Revolution,” Tinterow said.

Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910–1950 is a special ticketed exhibition and remains on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston through October 1.

Another view of the garden. Photo by Brian Austin, courtesy of Rothko Chapel.

Another view of the garden. Photo by Brian Austin, courtesy of Rothko Chapel.