"Molly Ivins: A Rebel Life" by Bill Minutaglio and W. Michael Smith details thefamous Texas writer's fascinating life.

"Molly Ivins: A Rebel Life" by Bill Minutaglio and W. Michael Smith details thefamous Texas writer's fascinating life. Seated on the right, Ivins joined her mother, Margaret, and sister Sara, brotherAndy, and father Jim at Houston functions.

Seated on the right, Ivins joined her mother, Margaret, and sister Sara, brotherAndy, and father Jim at Houston functions. Ivins maintained a lifelong passion for sailing, inviting friends aboard herfather’s boats.

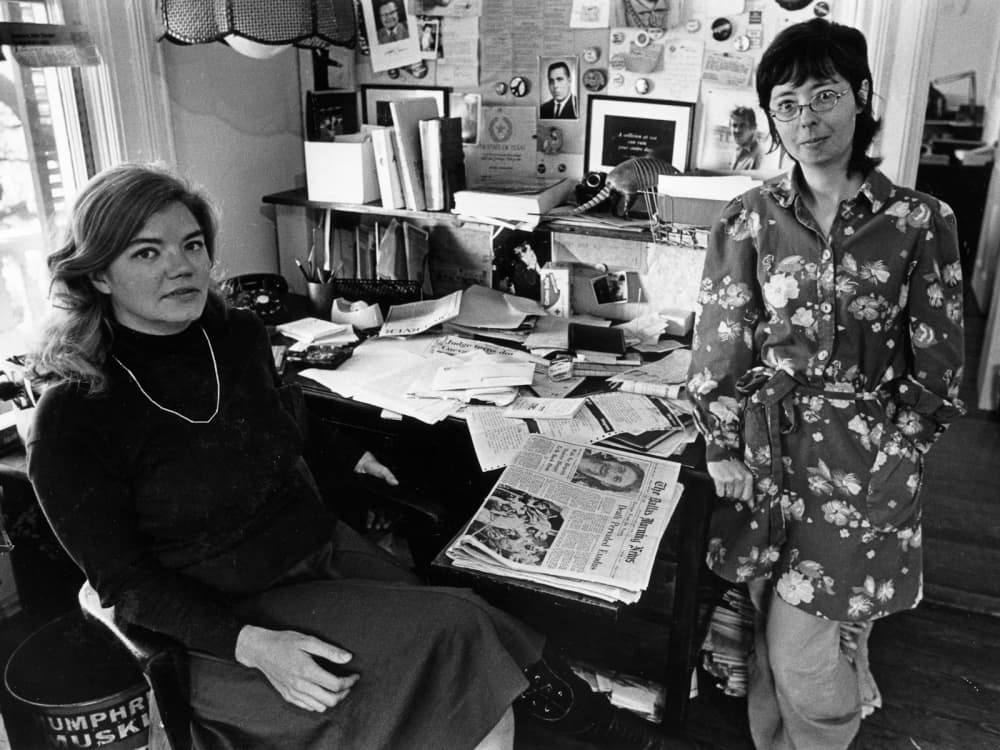

Ivins maintained a lifelong passion for sailing, inviting friends aboard herfather’s boats. Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott at The Texas Observer

Molly Ivins and Kaye Northcott at The Texas Observer Ivins during chemotherapy treatements for cancerThomas McConnell

Ivins during chemotherapy treatements for cancerThomas McConnell

When she was a child growing up in the River Oaks, Molly Ivins dreamed of being famous. If she didn’t make it by age 25, she wrote on a note tucked in her wallet, she would commit suicide.

That early promise is a key to the intensity and drive of one of the most provocative and influential figures in modern journalism. Before Ivins died of cancer at age 62, her column was appearing in more than 300 newspapers, three of her books had become national bestsellers and she was being offered $15,000 for speaking appearances.

An icon of liberalism in Texas, Ivins was a wise-cracking social commentator who inspired readers to both laughter and action, write authors Bill Minutaglio and W. Michael Smith in Molly Ivins: A Rebel Life (Public Affairs, $26.95).

Their entertaining, readable biography explores the life and times of a complicated woman who had a gift for humorously exposing the weaknesses of other people but was unable — or unwilling — to tackle her own demons.

Even if you agreed with her politics, Ivins wasn’t always easy to admire. She could be mean and unfair in print, was sometimes careless about using other writers’ material in her columns and was once famously accused of plagiarism by Southern humorist Florence King. Ivins apologized, the story was picked up all over the country, and she admitted to the American Journalism Review that she was depressed about it.

But love her or hate her, Ivins’ life makes fascinating reading. From interviews with over 100 of Ivins’ friends, colleagues, and family members, the authors reveal a woman little known outside her circle of close friends. In addition to all the personal stories, the book is full of vivid descriptions of postwar Houston, Austin and Dallas.

Born in 1944, Ivins was the daughter of a powerful, conservative Tenneco lawyer she battled with all her life. (He would end up leaving Ivin’s mother for a younger woman and blow his brains out in his 80s.) Her biography portrays a spirited girl who had an elevated opinion of herself (once writing her parents from camp that she was “superior to everybody”), who started smoking and drinking in high school, and who began spinning tales about Texas that had out-of-state school friends roaring with laughter.

As a young woman, she was also “a knockout,” one of her oldest female friends told the authors. At 6-feet-tall, Ivins had red hair, “a figure to die for, and was just gorgeous.” And although she never married, she would have a number of short affairs. The gossip about her in later years was that she had slept with Congressman Charlie Wilson, among other well-known political figures, and that she and Ann Richards, the late Texas governor and good friend, were lovers.

Ivins laughed at the suggestion she was gay. She came up with a stock response, describing herself as “a left-wing, aging Bohemian journalist who never made a shrewd career move, never dressed for success, never got married, and isn’t even a lesbian, which at least would be interesting.”

The love of her life was a brilliant, bold Yale student named Hank Holland who died in a motorcycle accident while still in college. The two were inseparable when she was at Smith College, and friends surmise she never married because she never found anyone else who could measure up.

Always interested in writing, Ivins interned for three summers at The Houston Chronicle, which the authors call “the early foundation for her boldly skeptical voice.” After graduating with a history degree from Smith College, she got a master’s in journalism from Columbia University before beginning a career in journalism. The best thing that ever happened to her, she would tell people for years, was The Texas Observer, a progressive bi-weekly publication of Texas politics and culture in Austin.

At the Observer, where she became drinking buddies with Austin activists, musicians and writers, Ivins was free to write what she thought and use the (often four-letter) words she wanted Her investigative, always entertaining stories attracted widespread attention, and she began freelancing for major publications and making speeches around the country.

Seeking more national exposure, she moved to New York in 1976 to work for The New York Times. But spoiled by writing pretty much as she pleased, she refused to follow what she called The Times’ “corporate style” and left to write a column for the newly-designed Dallas Times Herald. She hated Dallas, calling it “hopelessly boorish,” and the papers’ subscribers and advertisers hated her. The Times Herald ended up moved her to Austin, where she continued to write her column until the paper folded, when her column was picked up by The Fort Worth Star-Telegram and later syndicated.

Her first book, Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?, a collection of her short pieces, was published in 1991, became a bestseller, and she wrote several others, including two about George W. Bush.

By the mid-1990s, she had reached her goal of achieving fame, but her drive to do it was taking its toll. In spite of joining AA, she was unable to give up alcohol (and cigarettes), and even after being diagnosed with advanced breast cancer she continued to drink and smoke. And despite debilitating, month-long chemotherapy and radiation treatments, the cancer spread to her liver, brain and spine. She died in January, 2007.

Molly Ivins, a Rebel Life is a sobering account of the toll of addiction and cancer, but it’s also full of wonderful stories about a complex, brilliant woman who said what she thought, said it well, and made people — even if they disagreed with her -- laugh and think.