The Arthropologist

When your life becomes art: Bold artists tell thorny family stories

Memoirs of the Sistahood_Toni Valle of Memoirs of the Sistahood in "Chapter 2:House"Photo by Les Campbell

Memoirs of the Sistahood_Toni Valle of Memoirs of the Sistahood in "Chapter 2:House"Photo by Les Campbell Memoirs of the Sistahood, "Chapter 2: House," with Jennifer Dodson and ToniVallePhoto by Les Campbell

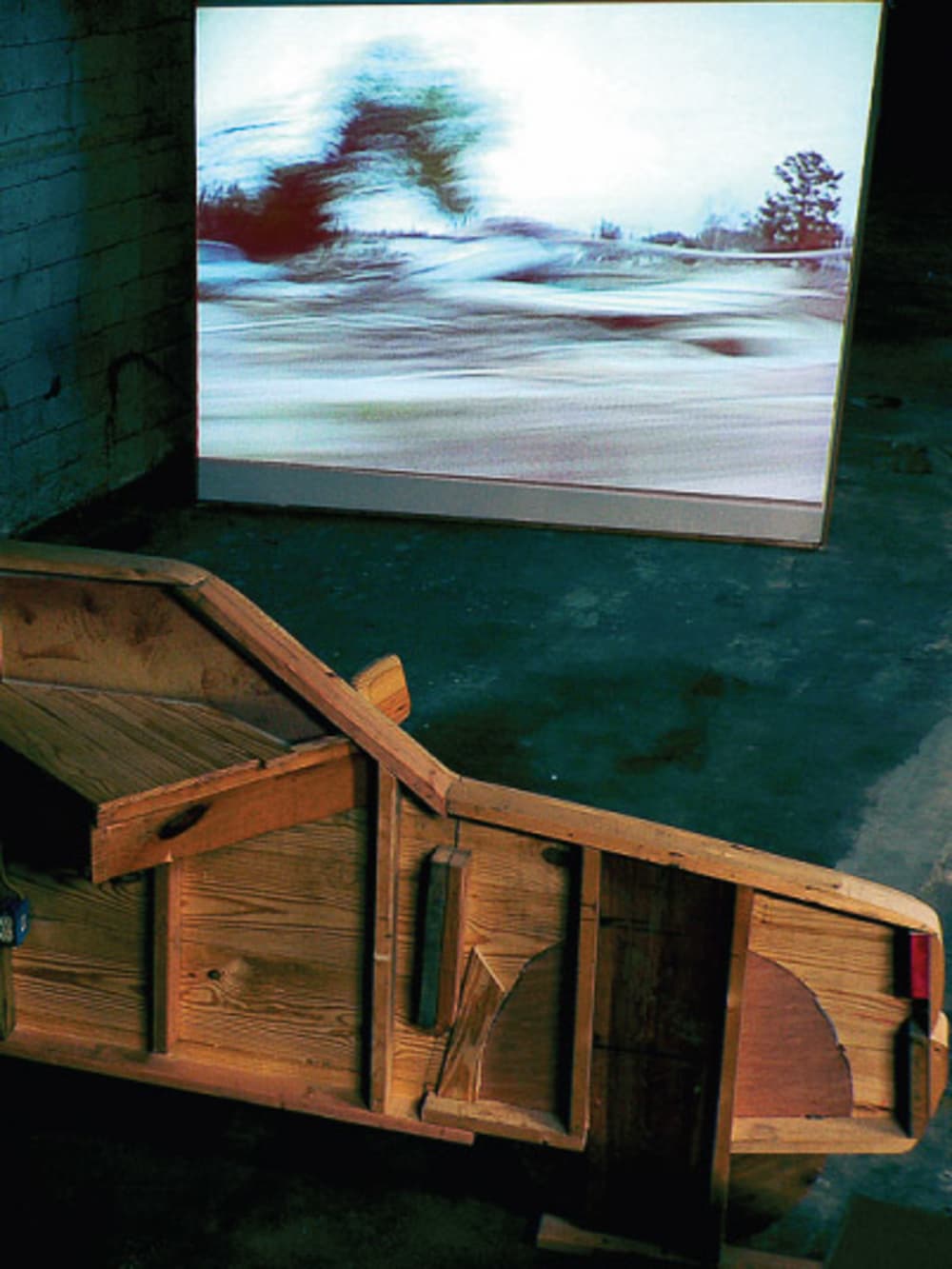

Memoirs of the Sistahood, "Chapter 2: House," with Jennifer Dodson and ToniVallePhoto by Les Campbell From "On the Street," front view of a life-sized wooden vehicle and a full bodyimage, which represents the Crier and his personal vehicle used whiledocumenting the disaster in the Lower Ninth Ward one month after Katrina hit

From "On the Street," front view of a life-sized wooden vehicle and a full bodyimage, which represents the Crier and his personal vehicle used whiledocumenting the disaster in the Lower Ninth Ward one month after Katrina hit Artist Rondell Crier and his brother Patrick Crier rebuilding their mother'shousePhoto by Rontherin Ratliff

Artist Rondell Crier and his brother Patrick Crier rebuilding their mother'shousePhoto by Rontherin Ratliff Memoirs of Sistahood's Joani Trevino, from left, Nicole McNeil and Mallory Hornin "Chapter 2: House"Photo by Les Campbell

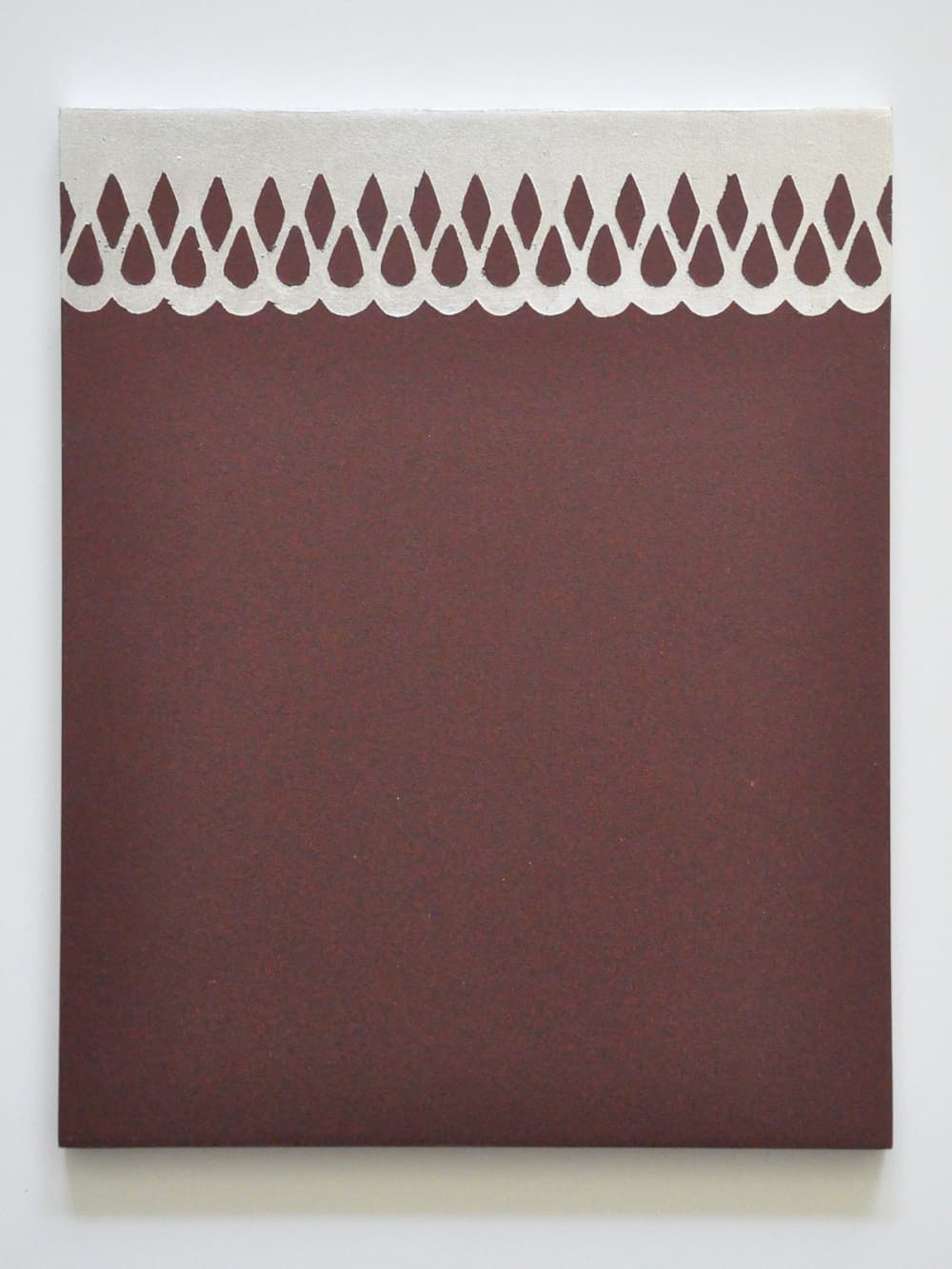

Memoirs of Sistahood's Joani Trevino, from left, Nicole McNeil and Mallory Hornin "Chapter 2: House"Photo by Les Campbell Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (envelope) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010

Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (envelope) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010 Crier's "On the Street," which was a video art installation on exhibit at aparallel enue during New Orleans' Prospect One Biennial 2008

Crier's "On the Street," which was a video art installation on exhibit at aparallel enue during New Orleans' Prospect One Biennial 2008 Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (purse) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010

Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (purse) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010 Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (compact) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010

Melanie Crader, "It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (compact) fromthe series The Eula Project," 2010

Once my mother caught me intensely watching my grandmother fold towels. She was suffering from Alzheimer's at the time, so repetitive movements seemed to calm her.

Captivated by the gentle, intentional quality of her gestures, I followed her every crease. "You are collecting material," my mother insisted. "You're going to use this in a dance, aren't you?"

She was right, I did, in a piece that traced my great grandfather's journey from Italy to Buffalo. I even used my mother's accusing statement. Afterward, my mother decided nothing much was safe around me. Real life existed just to provide ideas for dances. She did hand over my grandmother's embroidered organdy apron though, which I wore while telling my family's story.

Artists have been sourcing their own lives throughout history, rendering the details in various shades of truth, fact and fabrication. Melanie Crader also ended up with some of her grandmother's things, some 20 years after her death. A box of mundane objects such as a comb, some bobby pins, a lipstick case, a notepad and a compact served as the starting point for The Eula Project at University of Houston Downtown's O'Kane Gallery, opening Thursday night and running through October 7.

"I use the objects as source material to either write about or reference when making paintings and sculptures," Crader says. "They are abstracted and most often are only snippets or composites."

Crader's use of personal history takes an understated path, fragments of a narrative are present, pulling the viewer in, but taking them somewhere else in the process. Crader's piece, It all started when I tried to paint a portrait (compact) makes a bold statement, simultaneously amplifying and abstracting the original object.

Her work projects a clean formalism, free of sentimentality. The objects forced Crader to examine both the sketchiness of her childhood memories and her relationship with her grandmother.

"Memories are often altered, especially when there is no record of an event," she says. "I realized there were similarities between our lives, even though she died when I was very young."

Crader's work dwells in an elegant object quality, leaving traces of inspiration but adding a visual wit.

This entire project has taken me somewhere unexpected, as I have not worked in personal material in a long time," she says. "Being a Louisiana native, storytelling is a large part of the culture and definitely a defining characteristic of my interaction with others."

Sister, sister

When I sat down next to Beth, Barbara, Bitsy and Bonnie, only two of the Beaullieu sister's were missing. Becky Beaullieu Valls and Babette Beaullieu were back stage at Barnevelder, about to perform Memoirs of the Sistahood Chapter Two: House, an ongoing investigation of childhood, memory and growing up in Lafayette, La. Valls and her sculptor sister Babette have been collaborating since they premiered Memoirs of the Sistahood Chapter One at DiverseWorks in 2008.

"We start with memory, but use it more as a springboard rather than being confined by it," says Valls, who is an assistant professor of dance at University of Houston. "We needed to dig into memories to get to more archetypal images."

The Beaullieu sisters' work weaves a juicy collage of whimsical dance, theater and film, all cleverly housed in Babette's totem-like structures. Alternating between funny and poignant, the audience drops into a rich soup of life growing up in the 1950s in a large Catholic family in Louisiana.

The problem with autobiographical work is that sometimes the people you are telling the world about are not so happy. Valls heads into this territory knowing full well it comes with some sticky places. Like my mother, it took a while for Valls' sisters to completely bless the project.

"Two of my sisters were really angry," remembers Valls about the first piece. "It just shows the power of interpretation."

Valls assured her family she's interested in making a work of art not a tell-all memoir.

I just had the opportunity to witness Valls' approach to making dances at the Choreographers Lab at Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival. She mines her own history as a place ripe with raw material with an uncanny grace and sensitivity, in ways that feel inclusive, welcoming and not self obsessed. She invites the viewer into a shared world. Today,, the sisters are reworking Chapter Two: House for a show in New Orleans.

No escaping the house

For Rondell Crier, his life is his work, especially in his installation as part of Before (During) and After: Louisiana Photographers Respond to Katrina and Under-Standing Water at DiverseWorks (opening on Sept. 10 and running through October 23).

Crier is a painter, an illustrator and executive director of programs at YA/YA, a youth empowerment program. After Katrina flooded his mother's home, he began to reframe his life as an artist. Crier and his brother along with volunteers, rebuilt his mother's home, taking nearly two years to complete. His installation reflects and documents that process.

Crier remembers his mother's first steps inside her home after the flood.

"She was the first person to go inside. Six feet of water entered her house," Crier recalls. "Mold covered the walls, so everything she owned was damaged or lost. The experience forced us to re-think our livelihood."

Crier's installation lends a conceptual glimpse of flooding, devastation and the long haul of re-building. Some 5,200 5x7 photographs, depicting the full catastrophe of the event and its aftermath, spread out like a lake on the floor.

"I want people to be able to bend down and be close to an image, to have the feeling of digging through things," Crier says.

A gigantic water faucet, crafted from scrap wood and pieces of his mother's house, symbolizes the sheer scale of the flood. There's an epic feeling to the piece, deeply connected to the movement of water, from the flow of images to the curved shape on the floor, which appears to seep into the adjoining room.

"I like that people actually have to walk over these images to get to the rest of the show," Crier says. "It forces you to confront the details."

Crader, Valls and Crier intermingle their lives and art in a way that expands our notion of inspiration. It's a curious and completely accidental that all three of these artists hark from Louisiana.

Could it be that story is so in the bones of Louisiana artists that it's inevitable that their lives become the stuff of their art?

"Madonna" section from Memoirs of the Sistahood: Chapter 3. Choreography by Becky Valls: