Partners in art

More than a naked snow man: Dance with Camera blurs the line between artist andlens

robbinschilds + A.L. Steiner, "C.L.U.E. Part I," 2007, is part of Dance withCamera.

robbinschilds + A.L. Steiner, "C.L.U.E. Part I," 2007, is part of Dance withCamera. Joachim Koester, "Tarantism," is one of the exhibits that might make you rethinkhow dance and camera interact.

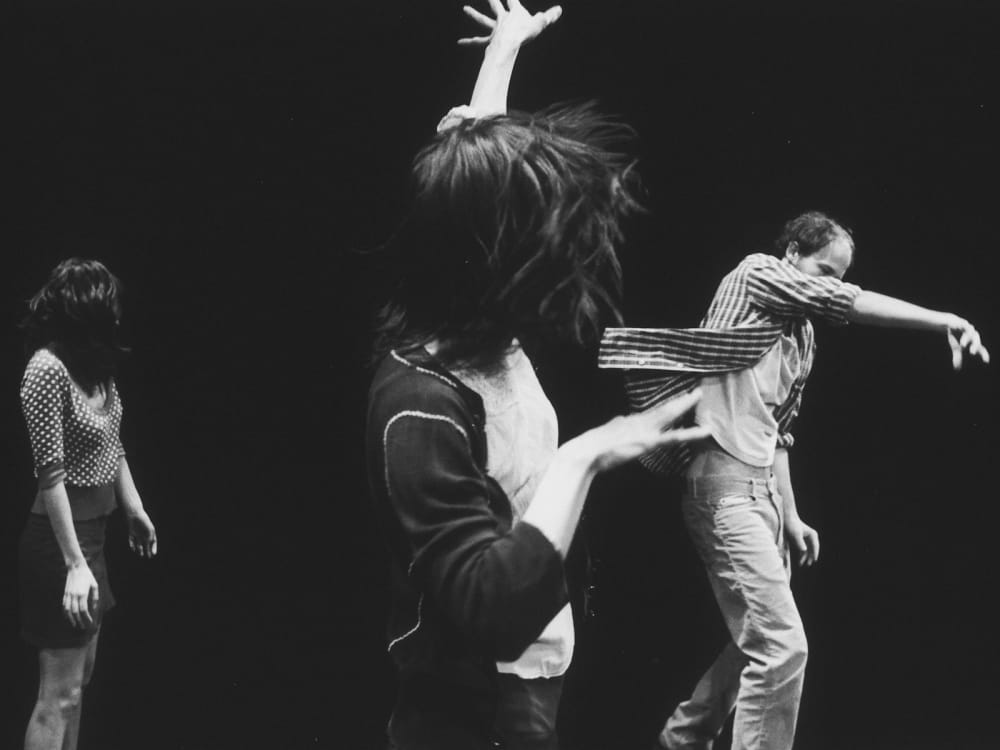

Joachim Koester, "Tarantism," is one of the exhibits that might make you rethinkhow dance and camera interact. Bruce Conner, "BREAKAWAY," a 1966, black-and-white film

Bruce Conner, "BREAKAWAY," a 1966, black-and-white film Kelly Nipper, "interval," 2000, four framed chromogenic process color prints,Museum of Contemporary Art and gift of the Disaronno Originale PhotographyCollection

Kelly Nipper, "interval," 2000, four framed chromogenic process color prints,Museum of Contemporary Art and gift of the Disaronno Originale PhotographyCollection

A naked man dances in the snow, while the late modern dance legend Merce Cunningham sits motionless at the opposite end of the room. A tarantella ritual explodes with a brutal raw energy, while Trisha Brown slows down time in a tucked away corner.

All of this made me stop in my tracks for Dance with Camera at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston running now through Oct. 17.

"With" is the operative word in this show.

"I describe the exhibit like a pas de deux, where the camera is partnering with dance," says Jenelle Porter, curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania and Dance with Camera curator.

"These are the works of visual artists. They only exist for the camera. None are records of a dance."

Porter makes us wonder, how a camera is like a dancer, in that it too moves, has a quality of motion, and is able to show us new and unconsidered angles for viewing. The camera is the dancer we never see, unless Charles Atlas, Cunningham's longtime video collaborator, happens to be involved. The exhibit includes two remarkable films by Atlas, one that turns the tables on the filmmaker.

A room full of dancers mid-motion packs a wallop whether it's live or on camera, so Porter isn't remotely surprised by my reaction.

"I did work with Toby Kamps on the floor plan for CAMH, but it's so different," Porter says. "At ICA, the show was more on a path, so the pacing was very planned. In the CAM installation, there are so many works in your view immediately. You can see almost everything from the midpoint of the space. That moment of seeing all those bodies moving in space came just slightly later in my version, so there was at first this kind of moment of quiet and stillness.

"For me, it was important to have bodies at all different scales, both time scales and size scales. Some pieces are so slow, even still, and some are exuberant and frenetic. My experience of the show is quite the same as yours, dazzled, as it was for many viewers in Philadelphia."

Not everything is in motion. Kelly Nipper's sequence of photographs, interval (2000), asks us to connect the dots ourselves, stringing together what happens between these images. "Opening with the Nipper photographs immediately throws off your expectation of the dance and the camera, and puts you in a position to be open to all these different types of relationships between the dancer and the camera," Porter says.

Dance with Camera is filled with abundant treasures, so pace yourself, visit often. Here are some of the dances that caught my eye.

Bruce Nauman's Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (1967-68) might take a little explanation. Nauman is a conceptual artist, not a dancer, yet he lived and worked around the renegade energy of the Judson Dance Theatre, coming into contact with such icons of an era as Yvonne Rainer. The written instructions for Nauman's piece begin with the words, "Hire a dancer."

He didn't, and the result has become a signature performance archive. The constant clicking of the metronome becomes the unattended soundtrack for the show.

Equally curious is the zany fake ballerina, Eleanor Antin in Caught in the Act (1973). Antin learned ballet from a book and well, it shows, making a very witty comment on pretense. Antin reveals what usually remains hidden, bringing the usual ethereal nature of ballet crashing down to earth with a thud and a snicker.

Another group of non-dancers grabbed my attention in Ann Carlson and Mary Ellen Strom's film of lawyers acting out the gestures from their lives in Sloss, Kerr, Rosenberg & Moore (2007). Carlson is famous for using real people in her dances, and here the authenticity is particularly powerful.

Bruce Conner's Breakaway (1966) busts entertainer Tony Basil into a million cuts, laying the groundwork of what would become music video decades later. Basil, recently seen on FOX reality show, So You Think You Can Dance as a guest judge, also performs the song. It's mesmerizing and considerably more interesting than what you would find on MTV any day.

Porter includes a little history corner. Plan to park there for at least 30 minutes or make several short visits. Here you can watch Brown dancing in real time and then again in slow motion in Babette Mangolte's Water Motor (1978).

It's like getting a little closer to Brown's uncanny sense of flow. There's a rare chance to watch William Forsythe dance in Solo (1997), directed by Thomas Lovell Balogh. Rainer's Hand Movie (1966) reveals the camera as a way to direct our attention to the protean dexterity of the human hand. But it may be Hilary Harris' Nine Variations on a Dance Film (1966) that kept me most transfixed.

The amazing Bettie de Jong repeats the same phrase over and over while the camera chooses a different way of showing us the movement. It's a chance to see exactly how a camera can deconstruct choreography.

The exhibit is loaded with community events, film showings and performances. Houston choreographer and filmmaker Lydia Hance of FrameDance collaborates with Rosie Trump for Points and Coordinates on Sept. 16. Anthony Brandt of Musiqa plans a Loft Concert with video by Be Johnny on Sept. 23. The Judson icon Deborah Hay presents Lecture on the Performance of Beauty on Oct. 2, while the exhibit wraps up with Navigating the Hallway, including dances by Leslie Scates, KDNY, Becky Valls, Teresa Chapman and Core Performance Company.

Oh, about that naked guy in the snow.

The Luis Jacob film is called A Dance for Those of Us Whose Hearts Have Turned to Ice, based on the Choreography of Francoise Sullivan and the Sculpture of Barbara Hepworth (2007). Keith Cole, a well-known performance artist, actually makes several references to Sullivan's dances during his snow dance. He is most definitely performing just for the camera, and for you, too, should you happen to wander into Dance with Camera.

Hilary Harris shows us every angle in Nine Variations on a Dance Theme (1966):