Truffaut & Godard Together On Screen

A Breathless look at the French New Wave highlights MFAH film series throughthis weekend

In 1959, critic-turned-filmmaker Francois Truffaut – whose incendiary reviews of the Cannes Film Festival had gotten him banned from that fest just one year earlier -- made his first big splash as an auteur at Cannes with his debut feature, The 400 Blows, his profoundly affecting and enduringly influential autobiographical drama.

One year later, Jean-Luc Godard – another outspoken firebrand who railed against the prevailing norms of cinéma de papa in the pages of the French magazine Cahiers du Cinema – plunged into feature filmmaking with Breathless, his stylistically audacious and exuberantly fatalistic neo-noir romantic melodrama.

Together, these two friends – destined, perhaps inevitably, to become competitive rivals, then bitter enemies – helped launch La Nouvelle Vague or, if you don’t parlez-vous français, the French New Wave, a loose-knit, deeply committed group of highly individualistic film directors who burst upon the international scene in general and the U.S. art-house circuit in particular during the heady days of the post-Eisenhower Era.

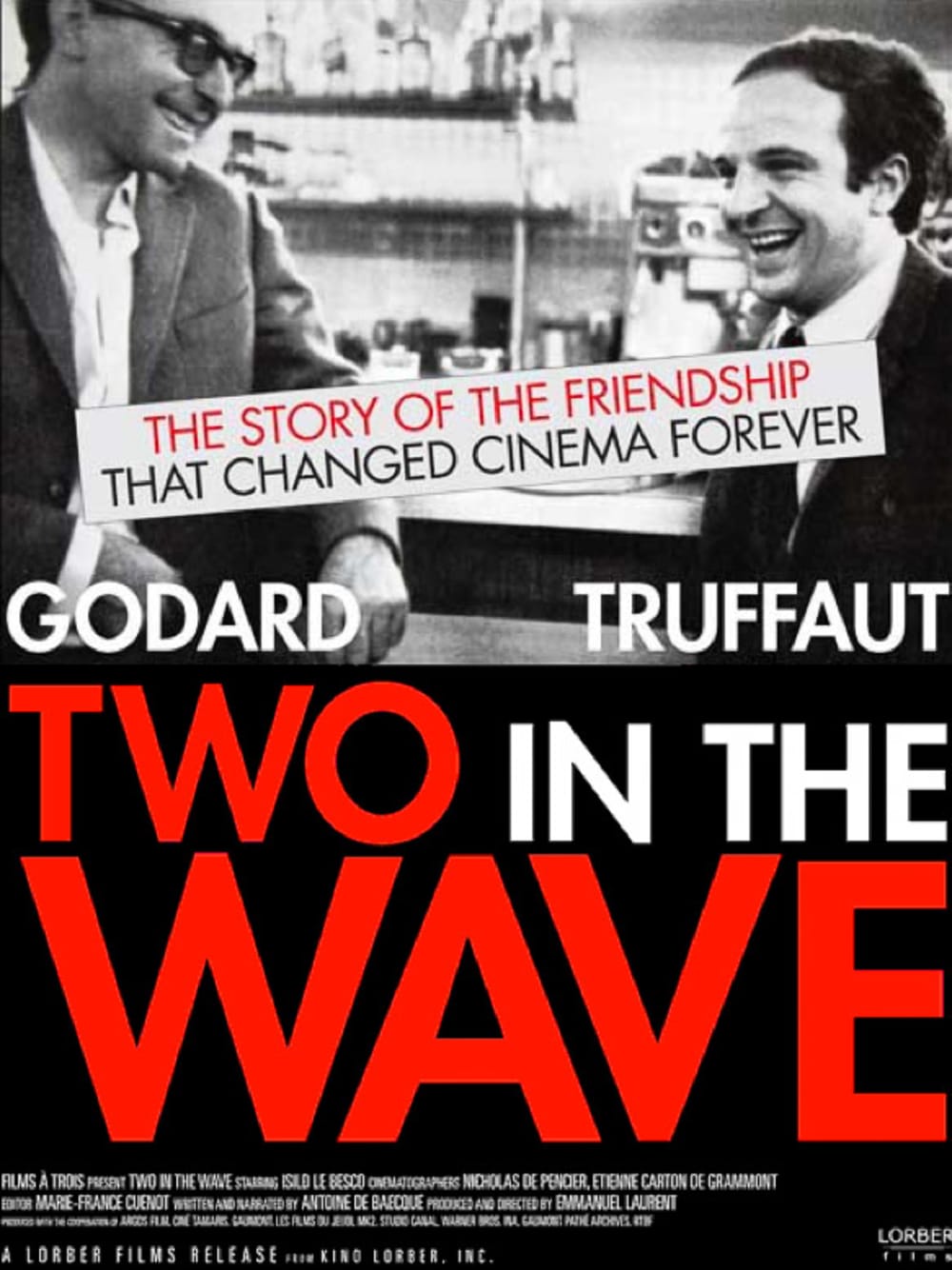

There were other notables in their ranks – including Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda – but it was Truffaut and Godard who, then and now, defined in the minds of most critics, academics and cinephiles the revolutionary vitality of a filmmaking movement influenced in equal measures by Italian Neorealism, Hollywood Classicism and anything-goes youthful audacity. So it is altogether fitting that director Emmanuel Laurent has chosen to focus almost exclusively on the early careers of those two artists in Two in the Wave, the celebratory documentary that will have its H-Town premiere this weekend at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Written and narrated by film critic Antoine de Baecque, who has authored authoritative biographies of both men, Two in the Wave is an ingeniously conceived and executed collage culled from newspaper and magazine clippings, newsreels and TV interviews and, of course, generous swaths of film clips.

Actress Isild Le Besco – a waif-like beauty with tauntingly plush lips – occasionally appears on screen to page through archival material, or visit historically pertinent locations in Paris. (In this, she recalls similar lovelies and their inquisitive wanderings in several agitprop films – Sympathy for the Devil, for instance -- Godard made during his post-1968 Maoist period.)

For the most part, though, Laurent’s cinematic essay sticks to backward glances, to illustrate how and why these men made their movies, the reactions those movies generated, and what led to the irreconcilable schism between the two New Wavers --Truffaut, a child of the streets saved by cinema, and Godard, the rebellious product of a well-to-do Swiss family -- who met as comrades in a cause, then diverged onto radically different paths.

Although it features a few clips from movies released after Truffaut’s Oscar-winning Day for Night, arguably the greatest movie ever made about the sheer joy of moviemaking, Two in the Wave is structured so that his 1973 masterwork triggers the documentary’s climax: Godard, with all the fury of a doctrinaire purist, sent Truffaut a letter excoriating what he saw as a betrayal of their revolutionary ideals; Truffaut, who would later joke that he frequently was accused of making the kinds of movies he might have attacked when he was a critic, responded in angry kind. The breach was never healed.

Truffaut, alas, is no longer with us – he died much too soon, at age 52, in 1984 – and while Godard remains active as a filmmaker, nothing he has produced since the 1970s – not even his aggressively provocative Hail Mary (1985) – has achieved an impact comparable to that scored by his genre-bending, often exhilarating ‘60s work. Still, both men continue to inspire and encourage later generations of filmmakers: Director Marc Webb freely acknowledges the “huge” influence Truffaut had on his (500) Days of Summer ; Quentin Tarantino named his production company A Band Apart after the original French title of Godard’s freewheeling 1964 pastiche Band of Outsiders (Bande à part).

You can savor for yourself the startling freshness and spiritedness of Godard’s Breathless as the MFAH marks the 50th anniversary of that film’s premiere with weekend screenings of an impressively restored 35mm print. Dedicated by Godard to Monogram Pictures, a Hollywood-based B-movie factory that churned out mostly low-budget features from 1931 to 1953, Breathless balances the brash impetuosity of reckless youth with the dead-end fatalism of film noir (a uniquely American genre that, appropriately enough, was named by French critics like Godard and Truffaut).

It’s the story of a hot-headed, self-dramatizing petty thief (an impossibly young, brazenly charismatic Jean-Paul Belmondo) who steals a car, impulsively shoots a motorcycle cop, then divides his time between frantically seeking funding for a getaway to Italy and dangerously dallying with a beautiful American girl (Jean Seberg at her most mater-of-factly luminous) who hawks the New York Herald Tribune on the streets of Paris. But that story – contributed by Truffaut in the spirit of New Wave solidarity – is merely an excuse for Godard to fashion a breezily free-form, semi-improvised riff on movie genres and conventions, charged by alternating currents of impatient restlessness (note the then-jarring “jump cuts” that accelerate the action) and indolent romanticism (a sizeable chunk of the movie is a slow-tempo seduction in a cramped apartment).

If you’re a true-blue cinephile, you’ll be amused by the movie allusions Godard cheekily tosses about like flavorsome garnish. For example: There’s a witty, in-jokey reference to a certain “Bob Montagné,” the protagonist of Jean-Pierre Melville’s street-smart Bob le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler), a 1956 drama often cited as an influence on New Wavers. (Turnabout is fair play: In Jim McBride’s under-rated 1983 remake-in-name-only of Breathless, someone is accused of ratting out a hood named “Johnny Godard.”) But, really, you don’t need to know anything about the movies that Godard references to appreciate that his film remains, even after five decades, almost shockingly vital and involving.

Now and forever, the New Wave continues to flow, unabated and undiminished.

(Two in the Wave will be shown at 7 p.m. Thursday, 8:45 p.m. Friday, 1 p.m. Saturday and 6:45 p.m .Sunday. Breathless will be shown at 5 p.m. Thursday, 7 p.m. Friday, 3 p.m. Saturday, 5 p.m .Sunday. Both films will be shown at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston's Brown Auditorium.)