Movies Are My Life

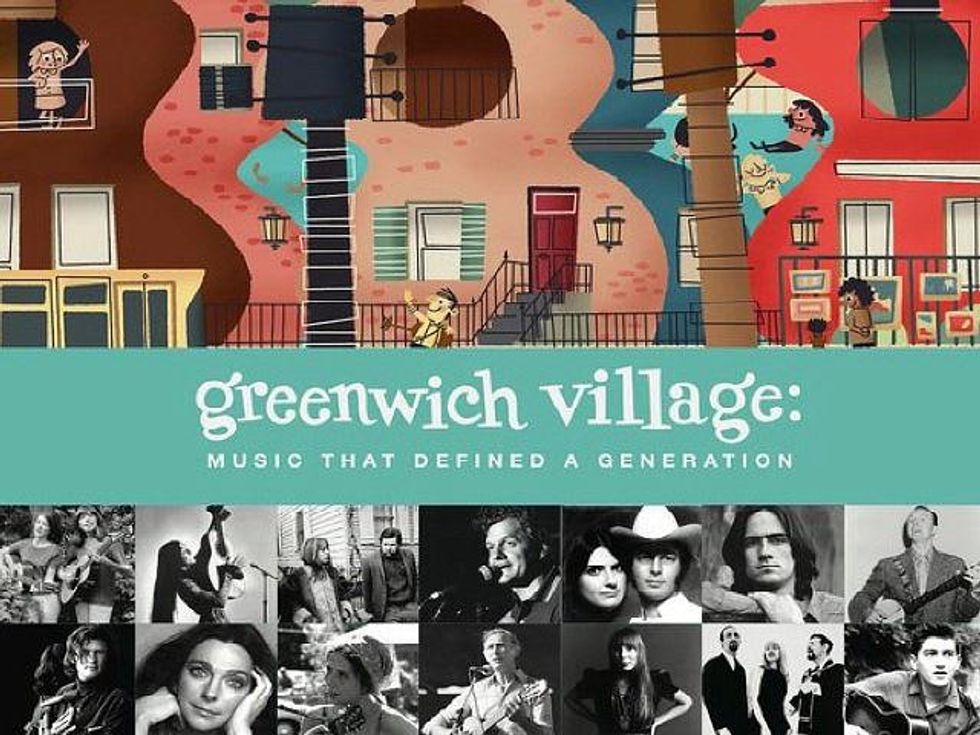

Bob Dylan's crazy Greenwich Village life is only the start: New movie brings music and a New York time alive

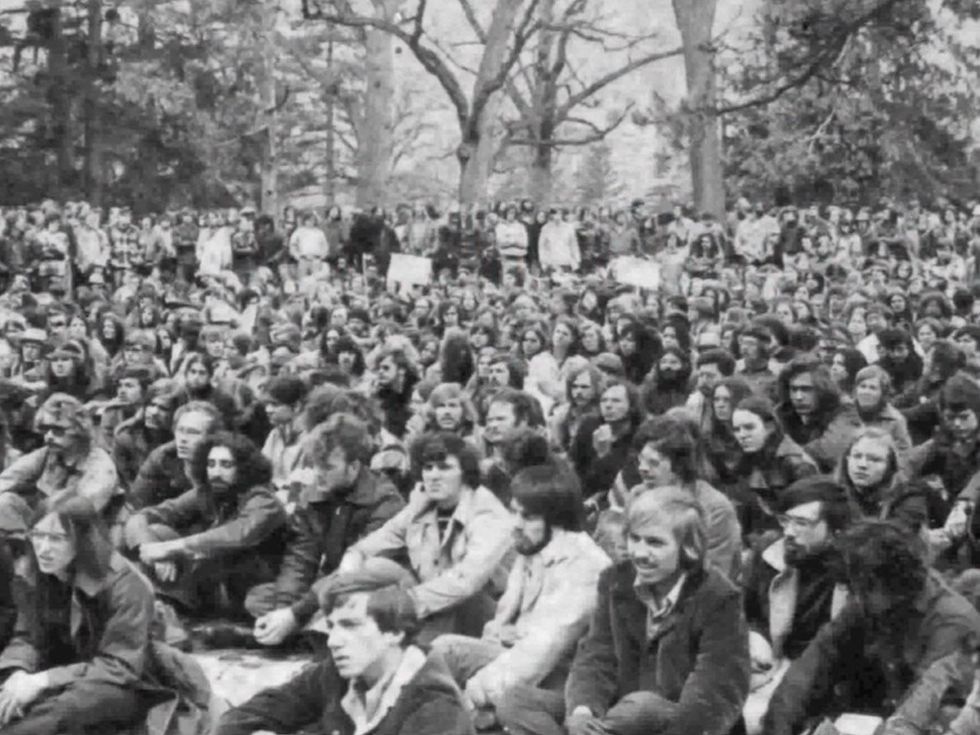

The times they were a-changing all across America throughout the 1960s and 1970s. But a disproportionate chunk of the soundtrack for this period of social upheaval was provided by the musicians living, sharing and creating in the same New York neighborhood.

Canadian-born filmmaker Laura Archibald details that fascinating phenomenon in Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation, an impressive and affectionate documentary about the socially conscious singer-songwriters who rose to prominence by challenging the status quo during the storied era of civil rights struggles, Vietnam War protests and cultural evolution and revolution. The film — which will have its H-Town premiere this Thursday, Friday and July 12 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston — combines illuminating interviews with archival and new live performances featuring such notables as Kris Kristofferson, Pete Seeger, Peter Yarrow, Judy Collins, Arlo Guthrie, José Feliciano, Don McLean and dozens more.

I caught up with Archibald a few days ago to talk about the ambitious goals she set, and the hard choices she made while assembling this cinematic history lesson.

CultureMap: When you’re dealing with a subject as multifaceted as the music scene in Greenwich Village during the 1960s and '70s, I would assume the hardest part is deciding just who you’ll include, and how much ground you can cover.

Laura Archibald: It’s funny you say that, because that truly was the hardest part: Deciding what is the focus, what kind of story do you want to tell, what perspective will you offer. It probably should have been a series, really. Or a documentary in two or three parts. It was a complicated thing to edit, of course. I started out with the idea of it being about Greenwich Village itself, and all the people who sort of passed through there, and the evolution of folk and rock. So we just laid it out in chapters, which seemed to be the easiest thing to do.

And then I went back to the idea of the focus being that specific geographical area, to give some idea of just how vast the talent pool was in this relatively small place. It was sort of like Tin Pan Alley in New York at a particular period of time, with all the songs that came out of there. Or like Nashville now — although that’s actually a little larger. Or the grunge scene in Seattle. Sometimes it seems like every community has a specific musical genre that’s being created there.

CM: Did it strike you as odd that there hadn’t already been scores of documentaries about the music of this particular place and time?

LA: I was pleasantly surprised, I suppose. But I went into it just thinking that a broader story needed to be told. It seemed like all the documentaries that had been made and the books that had been written were about Bob Dylan. And I figured there had to be a bigger story than just Bob Dylan, really. So I started reading other biographies, and starting conversations with people. And I began to realize how many hundreds of people went through the village, and started their careers there. So there was that story to tell.

"It seemed like all the documentaries that had been made and the books that had been written were about Bob Dylan. And I figured there had to be a bigger story."

Actually, my biggest regret is that there are so many people I didn’t get to talk to. That’s really a shame, because when you’re doing something like this, you want to include as many people who were involved as possible. But I figured that, at some point, you simply have to stop and make the movie.

CM: Bob Dylan is conspicuously absent from your lineup of interviewees. Did he turn down your requests to chat? Or did his manager just tell you to buzz off?

LA: [Laughs] Oh, no, he has a wonderful manager. But I just don’t think he does a lot of interviews. I didn’t have any high hopes that I would get him — but I did ask, of course. And in the chapter where I did cover him, I think I have people who were his peers making some great comments about him. If I were a musician, I would think the highest form of flattery I could receive would not be the dollars and cents at the end of the day, but rather what your peers think of you as far as your talent and songwriting abilities go. That’s a great statement.

CM: Of course, it’s funny to hear some of your interviewees admit that, when they first heard Bob Dylan, they were . . . well, underwhelmed.

LA: That’s true. But I think that might be true today when people listen to him for the first time. The first thing they might think is, well, he doesn’t have the greatest voice. So they just might not get him. I know that, personally, I have to go back to his ability to write some of the finest lyrics that you’ll ever read, so that I’m able to get past the voice. And as Jose Feliciano stated — well, maybe not the greatest guitar player, either, but that wasn’t the point.

CM: I must admit that, while watching Greenwich Village, I found myself thinking that, for the most part, these folksingers certainly appear much healthier and better-preserved than most rock stars of their generation.

LA: Well, I know that many of them did not escape the '60s unscathed, either. But maybe it’s what’s in their hearts. I’m not saying anyone in rock ‘n’ roll has a different heart. But I think their focus early on was, like Judy Collins stated, “What can we do to help other people? How do we get involved, and make change?” Maybe there’s something about having that little fire always burning that helps burn off all the other excesses, all the toxins that might have gotten in your body during the 1960s.

Greenwich Village: Music That Defined a Generation will screen at 1 p.m. Thursday, July 4, and 7 p.m. July 5 and 12 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.