The Review Is In

A ballet to silence the doubters: Houston Ballet's Journey is beyond masterful — and funny

This journey might have only three stops — Russia, Czechoslovakia, and America — but it’s still one of the most thrilling trips imaginable. Houston Ballet’s current rep program is elegant, powerful, and hilarious, in that order.

All three ballets are certified classics.

The first and oldest work on Journey With the Masters is George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial, which premiered in 1941. I think it’s reasonable to describe it as a Russian piece, even if it was created in America and then premiered in Rio de Janeiro. In his choreography, Balanchine chose to celebrate both the Imperial Ballet of his childhood and the legendary Marius Petipa (choreographer of such classics as Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker). The score is Tchaikovsky’s second piano concerto, unmistakably Russian, even in its high-Liberace moments.

If you’re trying to win friends or family members over to the virtues of ballet, you must take them to see this piece.

Technically, it is a fiendishly difficult and lengthy ballet, calling for a huge cast of soloists, demi-soloists and corps-de-ballet artists. I’ve always felt there are deep metaphors buried in the seemingly formal episodes of the ballet’s three scenes. This is a deceptive piece that promises pomp but secretly acts with a twist.

I don’t recall ever seeing it performed with a painted backdrop, but obviously I have never seen the Rouben Ter-Arutunian set, which Houston Ballet uses for this production. It tastefully recalls the glorious Winter Palace, even if the baby-blue and orange light chandeliers look tacky. I remembered this work as cleaner and less decorative, but memory is also deceptive. Ter-Arutunian’s costumes here are opulent, if not magical.

Houston Ballet could have taken on an easier, shorter work by Balanchine. Instead, the company decided to tackle a grand masterpiece. The result, after only the opening-night performance, is largely a success. Subsequent ones will only improve as the dancers settle more deeply into the work.

The corps-de-ballet dancers were noticeably too staggered in the opening scene, which demands military precision. Certain unison passages for the arms or legs were haphazard, even messy at times, suggesting that the corps lacks a singular understanding of the phrases. When Sara Webb entered after a few minutes, however, it was as if she had cleared the air with her prowess.

Her short solo was extremely confident, winning spontaneous applause. Shortly thereafter, Simon Ball garnered more applause for his fluttering, high-flying double cabrioles. Oh, the softness of each landing! He and Webb demonstrated utmost musicality throughout the three scenes. To my eye, they look like accomplished Balanchineans, with the characteristic speediness and exacting body direction. The ragged corps, however, appears to have been neglected in rehearsals.

Watch this ballet carefully, and you’ll find moments that are truly daunting. These include Simon Ball’s “pas de trois” with 10 women (five on each arm), the grand jetés the second-soloist men must complete while promenading a ballerina (these always make me wince at their difficulty), and prima ballerina Sara Webb seemingly lost in a crisscrossed corps-de-ballet sea in the final scene.

The Backstory

When Jiří Kylián choreographed his famous Sinfonietta in 1978, he hadn’t been able to visit his family in Czechoslovakia for 10 years. The score, a symphonic poem by Leoš Janáček, was composed in 1926. In spirit, it seems to look back at the first World War.

Both the composer and the choreographer are recognized for their sense of nationalism blended with humanism. This is a triumphant, expressive and perfectly-made dance. As performed by Houston Ballet, it is irrefutably noble as well. And the problems noted in Ballet Imperial do not exist here, because Sinfonietta is choreographed for seven male/female couples of equal standing. Kylián’s seeming lack of hierarchy in his works is one of many reasons, I think, that his dances appeal to contemporary audiences.

There is nothing to complain about here, and Houston Ballet’s dancers are nothing short of sublime.

From the opening parallel major-minor trumpet fanfares, with their overwhelming series of leaps for the men, to the final scenes where the dancers face upstage and slowly extend their arms to a cruciform position, this ballet is inspired and archetypal. The five-movement work is filled with dense partnering, which makes it seems like an intricate puzzle is being completed before your very eyes. There is nothing to complain about here, and Houston Ballet’s dancers are nothing short of sublime.

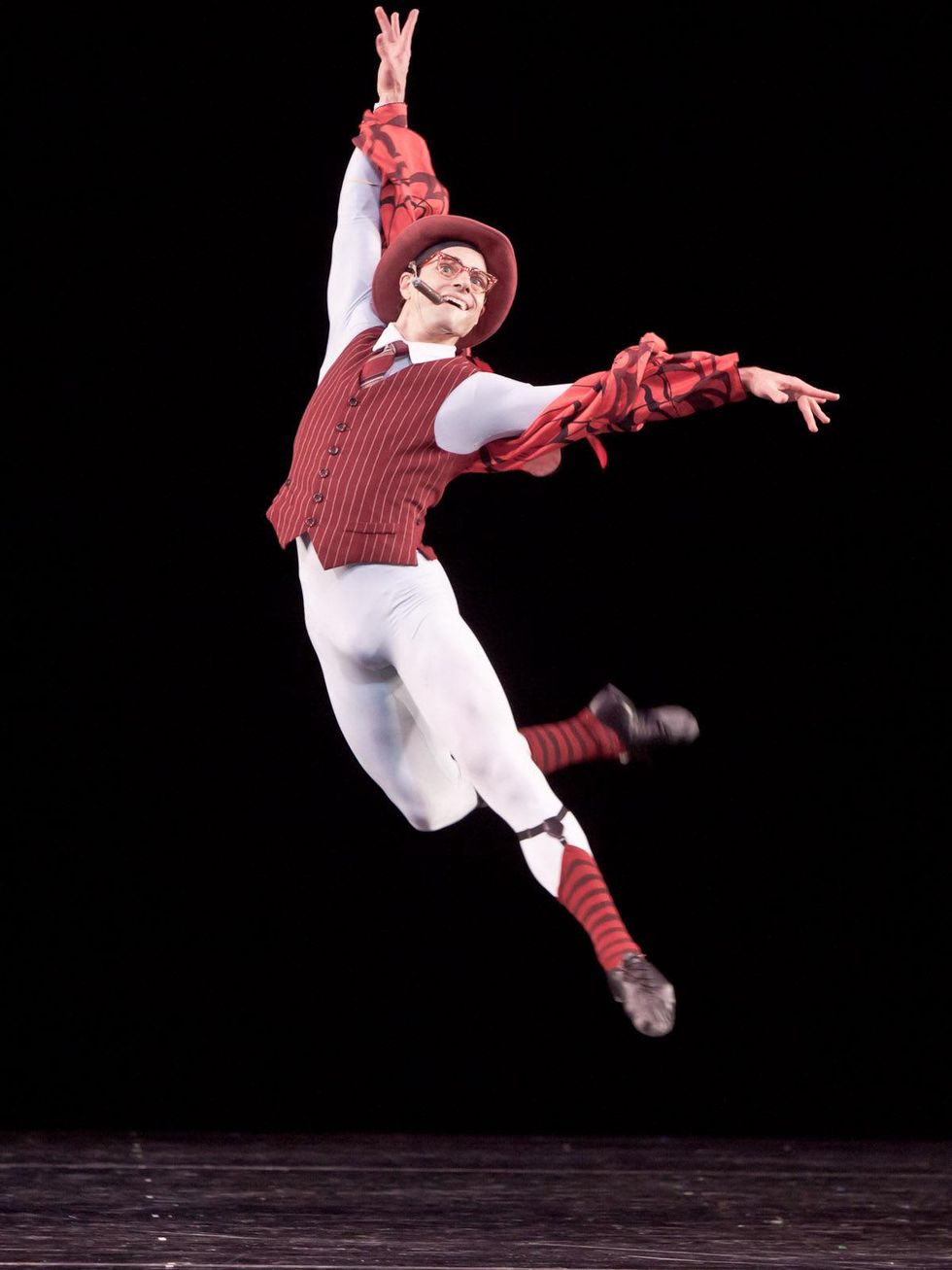

It’s been some years since I’ve seen Jerome Robbins’ The Concert, a ballet that stands out as one of the few humorous works in the modern repertory. It never gets tiresome, because it is one of the most tender and honest dances ever made. If you’re trying to win friends or family members over to the virtues of ballet, you must take them to see this piece.

When it premiered in 1956, theatrical vaudeville might have been in its twilight, but the vaudeville aesthetic was still alive and well on television variety shows. Houston Ballet captured the gags and pratfalls with that most important element of comedy, namely, timing.

I don’t know anyone who doesn’t adore this ballet, and in the context of Journey with the Masters, there are moments when it seems like Robbins is poking fun at both Balanchine (for his formality) and Kylián (for his stoicism and expressivity). Pianist Katherine Burkwall-Ciscon gives both frenetic and pastoral interpretations of Chopin, as needed throughout the numerous scenes. I won’t give any spoilers, but let’s say you’ll never watch a butterfly quite the same after you’ve seen such an expert staging of The Concert.