Take notes Madonna

Shining a light on Islamic mysticism: MFAH's new Sufis exhibit shows it's morethan Kabbalah

Pouran Jinchi, Untitled, etching 1998© Pouran Jinchi, courtesy Art Projects International, New York

Pouran Jinchi, Untitled, etching 1998© Pouran Jinchi, courtesy Art Projects International, New York "Five Holy Men" (detail), c. 1670, signed by Riza ´Abbasi

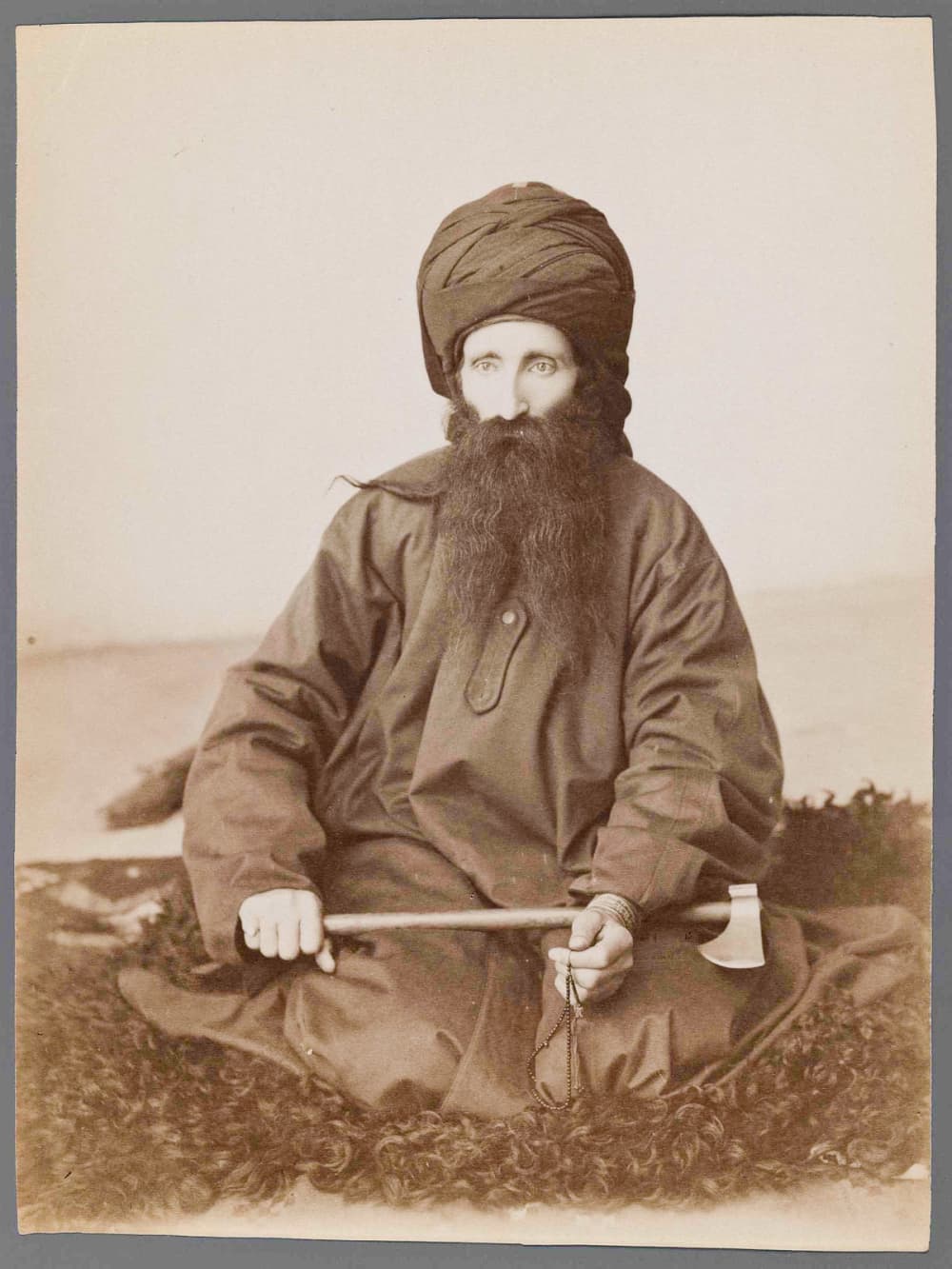

"Five Holy Men" (detail), c. 1670, signed by Riza ´Abbasi "Portrait of a Dervish," possibly Antoin Sevruguin of Qajar, Iran

"Portrait of a Dervish," possibly Antoin Sevruguin of Qajar, Iran

You don't have to be Madonna to be interested in mysticism. Lately, a number of highly publicized celebrity dalliances with Kabbalah shed light on contemporary interest in religious practices dating from the Middle Ages. The Museum of Fine Arts Houston's "Light of the Sufis: The Mystical Arts of Islam" trains its powerful spotlight to great effect on this fascinating if lesser known aspect of Islamic faith.

The show, which runs Sunday through Aug. 8, demonstrates the museum's relatively recent (some might say long overdue) commitment to fill a noticeable gap in its holdings. According to MFAH director Peter Marzio, the museum is now positioned to build an "ecumenical" as opposed to a "encyclopedic" collection honoring the arts and culture of a faith that stretches across many continents and centuries

Islamic artistic and cultural traditions are now at the forefront of the museum's fundraising and curatorial agenda.

"Light of the Sufis" was curated by Ladan Akbarnia of the Brooklyn Museum for a NYC festival last summer called Muslim Voices. The show, which opens substantially expanded by the MFAH's recently-hired Islamic curator Francesca Leoni, demonstrates that ancient mysticism speaks just as well to contemporary Houston.

The tantalizing possibility of mysticism, an experience of communion with the divine, took the form of meditation, discipline, philosophy, and poetry. This philosophy unites many otherwise discordant world religions, including Judaism, Islam and Buddhism. The show places Islam at the center of the development of overlapping traditions stretching from present-day Eastern Europe to China, India and beyond.

"Light of the Sufis" takes its title quite seriously by tracing the analogy between divinity and light articulated in the Quran to explore how material objects attempt to capture the spirit of mysticism through a play of light and darkness. Viewers of the show will encounter everything from mosque lamps, candlestick bases and torch stands, which literally convey light, to paintings, photographs, drawings and sculptures of practices designed to bring enlightenment.

Here are a few things to keep in mind as you follow the path of the ancient Sufis right into everyday Houston:

1.) Communion with the divine is impossible to depict. How can any object, whether a painting or a poem, represent the ineffable?

This defining contradiction was not inhibiting to practicing mystics and artists. It was invigorating. Certainly, the show features wonderful depictions of ascetics. The late 1st-century Five Holy Men represents the broadly ecumenical nature of Sufism, which attracted reverence from man and women of many nations, even those who were not followers of Islam.

And don't miss the haunting immediacy of two late 19th-century photographs: Family of Dervishes and the solitary Dervish. These photos anticipate wonderful contemporary works that struggle to represent devotional practices. Contemporary Turkish artist Mehmet Günyeli's startling series "Dervishes" seems to concentrate circles of these iconic practitioners, seen from above in the midst of an utterly black background, to their signature conical hats.

2.) The term "sufi" is believed to derive from "suf," which refers to the wool making up the coarse garments of mystics. It is fascinating that a religious practice dedicated to renouncing the material world would inspire such sumptuous objects.

Note the three traditional begging bowls crusted in silver, carnelian, and turquoise. These bowls were and made of rare coco-de-mer shells that would wash up on the shores of southern Iran from the waters of Indonesia.

The impoverishment characteristic of mystical practice leads was supposed to lead to the riches of enlightenment. But if you think those begging bowls are opulent, try contemporary Iranian artist Farhad Moshiri's Esgh (2007). Hundreds of luxurious Swarovski crystals glitter on an uneven black surface. The crystals form a milk way like swirl out of which emerges the Persian word "Esgh," which refers to passion for the divine.

There's rich illumination in Moshiri's gorgeous composition, and also a signal that many forms of Islam are entirely about love.

3.) You know more about Islamic mysticism than you think. Take, for instance, the works of 13th-century Persian poet Rumi, which now adorn so many greeting cards and calendars it would be hard not to have heard of him.

But greater subtleties abound in "Light of the Sufis" than the reduction of poetry to slogans. For Rumi, union with the divine could be described in the language of passionate or erotic love.

There's love aplenty in the story of Majnun and Layli, whose tumultuous affair might remind us of medieval romances. This love drives Majnun's madness and exile and represents the sufi's humility, impoverishment, and dedication to divine love.

You'll find this represented in a wonderful page from an illuminated Iranian manuscript Layli u Majnun. The arts of calligraphy and book-making enabled the representations and transmission of Islamic mysticism. Nothing adapts Rumi's own love of the ineffable as well as Kelly Driscoll's Fragments of Light.

Laser-etched on overlapping panes or pages of glass, you'll find Rumi's unforgettable verse: "The window of my soul opens fresh in delight." Poetry about the light of the divine is perhaps best conveyed through the transparency and fragility of glass.

4.) The idea that art is either Islamic (and therefore religious) or contemporary is entirely false. The most compelling pieces, including those by Driscoll, Moshiri, and Günyeli make this abundantly clear.

But don't miss Parviz Tanavoli's ode to what mystics call the darkness or apparent absence of God that precedes illumination. Heech, a sculpture of the Persian word for nothing, rises in the center of the gallery like the bodies of lovers as depicted by Brancusi.

And just behind this hang Afruz Amighi's 99 Names, a curtain of beads whose overlapping textures spell out the 99 names of God, the reciting of which remains an important devotional practice. And Pouran Jinchi has blossomed more or less directly from the ancient practice of calligraphy into a gorgeous textual art in works like Untitled (1998), in which characters swirl up from scarcity to abundance, like a tornado or a whirling dervish.

5.) Houston may be late to the collection of Islamic art, but it is trying to make up for lost time. Curator Leone acquired Portrait of 'Ali, Hasan, Husayn, and Nur 'Ali Shah Ni'matullahi, which depicts Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, in a halo of mystic light.

And she managed to discover and identify a rare 18th-century dragon carpet in the Bayou Bend collection, which was purchased by Ima Hogg in 1960. As usual, Houston's original patrons displayed admirable foresight.

It's hard to imagine a better time for the MFAH to continue the work of educating Houston about the rich and varied traditions of the Islamic faith.