Holocaust Museum Honoree

Courage Award winner Mia Farrow on the hope of college campuses, The DarfurArchives & her Houston Symphony connection

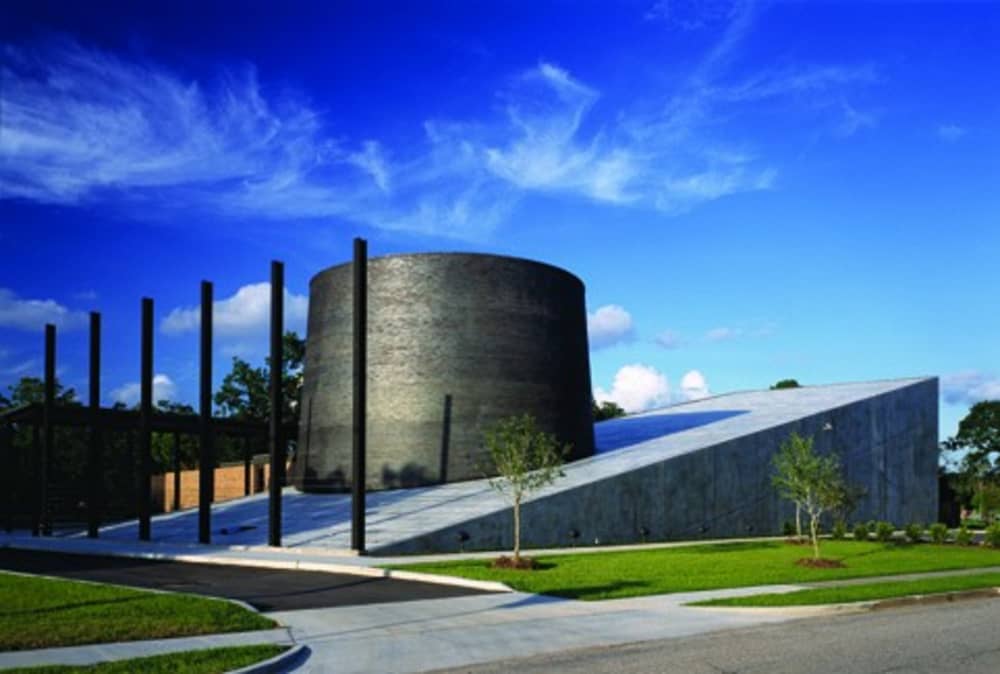

The Holocaust Museum

The Holocaust Museum

AP Photo

AP Photo Mia Farrow

Mia Farrow

The Holocaust Museum Houston established the Lyndon Baines Johnson Moral Courage Award in 1994 in tribute to the former president's efforts as a young congressman, in which he risked his personal dreams to provide American sanctuary for threatened European Jews in 1938. Actress, activist and humanitarian Mia Farrow has been identified as the recipient of the 2011 award, which will be presented during the museum's annual dinner, themed "With Knowledge Comes Responsibility," on Wednesday night.

Farrow took time to speak with CultureMap about her activist pursuits, the meaning of the award and her decision to leave her career in film.

CultureMap: What was the impetus for your pursuit of humanitarian causes?

Mia Farrow: In 2004, I read in the New York Times about an ongoing genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan. It was actually the 10th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide. It's extremely hard for me to understand that time for multiple reasons.

My country, the church and the United Nations all failed to intervene and help the people of Rwanda. I wondered what was so compelling during that time that I didn't even notice. I looked back, and it was the time of the O.J. Simpson murder trial. My country and the press were preoccupied with a celebrity murder trial while other people were being hacked to death.

When I heard about another genocide that was falling behind the mainstream media radar, I quickly got myself to Darfur, and I came away a witness — a witness to genocide. I came up with an initiative against the Chinese oil companies that were underwriting the violent campaign in Darfur. I did research and found that my own savings with Fidelity Investments were being used to purchase the weapons there. And I thought that people should know.

I started my website purely to convey information so people wouldn't have to scour the Internet for hours everyday like I did. It was part of my effort to elevate awareness of the genocide in Darfur so that people couldn't turn away. Perhaps more people would have perished would there not have been some light put on it. That's not to say people aren't suffering still. One hundred thousand people have been displaced in the last year, and people are dying.

CM: Can you explain the theme of the museum's event, "With knowledge comes responsibility"?

MF: I always tell my children that with knowledge comes responsibility. If we know that somebody is suffering and that there is an injustice, then we must do our best to correct it, now matter how small our contribution. It takes all of us pushing behind a cause.

After becoming a witness to the genocide in Darfur, I began traveling from university to university. I've given up on old people; we've become apathetic. That's not the atmosphere at college campuses, where I saw students galvanized across the nation.

CM: What can viewers expect to find in your current project, The Darfur Archives?

When I saw that so much was being lost, with almost three million people living in deplorable conditions in refugee camps, I decided to compile archives of the catastrophe. What struck me was noticing that the people's cultural traditions were not being practiced at all.

People were in mourning, so they thought it unseemly to engage in their celebrations as in times past. Most of their celebrations were tied to the land: planting, harvesting, raising roofs and visiting neighboring villages. That's all been lost. Not just in terms of massacred people, but the land and the way of life are lost, including the celebrations.

Darfur is not a culture of museums and preservation, but these fading traditions needed to be documented. So I got a topnotch video camera and went to document with someone from Human Rights Watch.

If you go to miafarrow.org and click, "The Darfur Archives," there's a little nine-minute movie about the project. You'll go into the camps, meet the people, and you'll see refugees trying to replicate the ceremonies: the making of drums, distinct shoes for the rainy season and dry season, all sorts of children's stories. We have gone back 300 years by speaking to the elderly.

A culture's treasures lie in its own memories. As the elderly people are dying, so are the society's most valuable possession — their traditions. It's very special to have the stories told by grandparents, who lived in the time when elephants and tigers roamed Darfur.

What's more, people have been in the refugee camps for eight years now. The children who came at age seven can't remember farming and ceremonies. How would they survive?

My promise to them was that a museum would one day exist. When peace comes, the children will be able to go to the museum and reclaim what is theirs. The archives are being professionally created at the University of Connecticut Dodd Center for Human Rights. It will also be on the Internet.

CM: What is the current status of your effort in Darfur?

MF: We haven't ended it by any means. I'm still out there talking to anybody who will listen. If people want to learn more, they should call 1-800-GENOCIDE. To put the effort into perspective, I'll tell you a statistic: If at least 100 people from each district would have contacted their congressman, we could have caused an intervention in Rwanda. Because in America, we have a voice. It matters what we think. With that privilege, we have a responsibility.

CM: What advice would you offer to aspiring activists?

MF: I think if they are aspiring, then they are already activists. Be among the dreamers, but don't stay at the dream level.

Our worst enemy is our own feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. Engage in whatever compels you. I know people who are addressing human trafficking — very young prostitutes, which is a kind of slave trade in particular cities. People don't have to get involved in Africa, but it's very difficult to turn away.

CM: How does your background in film impact your humanitarian efforts?

MF: As an actress, I knew there were particular things I could use. Here I am, giving an interview. I am also able to make my photographs available to everyone. Whenever people are writing about Darfur, they're looking at photos I took. I know that because I don't see anyone else there.

I also get to write in publications like Huffington Post and Wall Street Journal. I'm at a point in my life where I cannot ignore that people are imperiled. And I'm making good on a promise to people who say, 'We need protection.'

CM: What is your next project?

MF: The Darfur Archives is still the biggest project in my life. Also, I still have one child living at home, a 17-year-old. So, I'm still a mom, and I have nine grandchildren, and two of them live with me part-time. I'm busy!

CM: Your latest movie, Dark Horse, will be released later this year. Can you describe your role? Will you be pursuing more work in film?

It's done by a wonderful director, Todd Solondz, who is also a friend. And I work with Christopher Walken, which is great. Walken's character is Jewish, and even though he is Polish with blue eyes, he wore a wig and brown contact lenses to fill the part.

My character channels Joan Rivers — I wear a wig that looks like her. It's a dark comedy, and it's going to be terrific. However, my last memory while filming was thinking, "This isn't what I'm supposed to be doing. I'm supposed to be in camps working on my archives."

CM: Will your acceptance of the Johnson Award be your first visit to Houston?

MF: I went to Houston when my ex, André Previn, was the conductor of the Houston Symphony orchestra. I was then in the early days with André — way back! I'm looking forward to coming back.

Farrow's award will be presented at Holocaust Museum Houston's annual dinner at 6 p.m. Wednesday.