Three Chances To See It

Racism and identity collide: Tackling The Reconstruction of Asa Carter meant tracking a slippery mystery

Editor's note: With The Reconstruction of Asa Carter airing on Channel 8 HoustonPBS at 8 p.m. Tuesday, 1 a.m. Thursday and midnight Sunday, executive producer Laura Browder lets CultureMap readers in on the movie-making process and more from a story that's stranger than fiction.

The scene is a small trailer home tucked away in the Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina. Douglas Newman and I wait patiently with our cinematographer for our host, the noted Cherokee storyteller and artist Freeman Owle, to finish carving a wooden bird he’s been working on for a week.

After 20 minutes, Owle puts down his chisel and ambles over to the couch to discuss with us the legacy of Forrest Carter, one of the most well known and widely read Cherokee authors.

It asks what it is about American discourse that makes us accept such persons so readily — and then feel so betrayed when their deceptions are exposed.

Although he has been dead for more than 25 years, Carter’s best-selling memoir, The Education of Little Tree, continues to touch people’s lives. It is, in fact, required reading in many multicultural literature classes across the nation. Published in 1976 by Delacorte Press, the book recounts the idyllic life of an orphaned boy learning the Way of the Cherokee from his sage Native American grandparents in the hills of Tennessee.

Carter’s chronicle was lauded by critics for its authentic portrayal of the American Indian experience, and it became a hot seller in Indian reservation bookstores across the nation. Yet in 1991, after sales of Little Tree had topped half a million copies, an op-ed piece in the New York Times broke the news: The critically acclaimed Cherokee memoir was a fake.

Not only was Forrest Carter not the Native American he claimed to be, but he had walked a long and very different path as the professional racist Asa Carter. Even Carter’s new first name, readers learned, had been taken from Nathan Bedford Forrest, who founded the original Ku Klux Klan. Articles on Little Tree’s identity appeared in Newsweek, in Time and in Publishers Weekly. Fans of the book were shocked, as were friends from Forrest’s later years in Texas, for whom he would, after a couple of drinks, perform Indian war dances and chant in what he said was the Cherokee language.

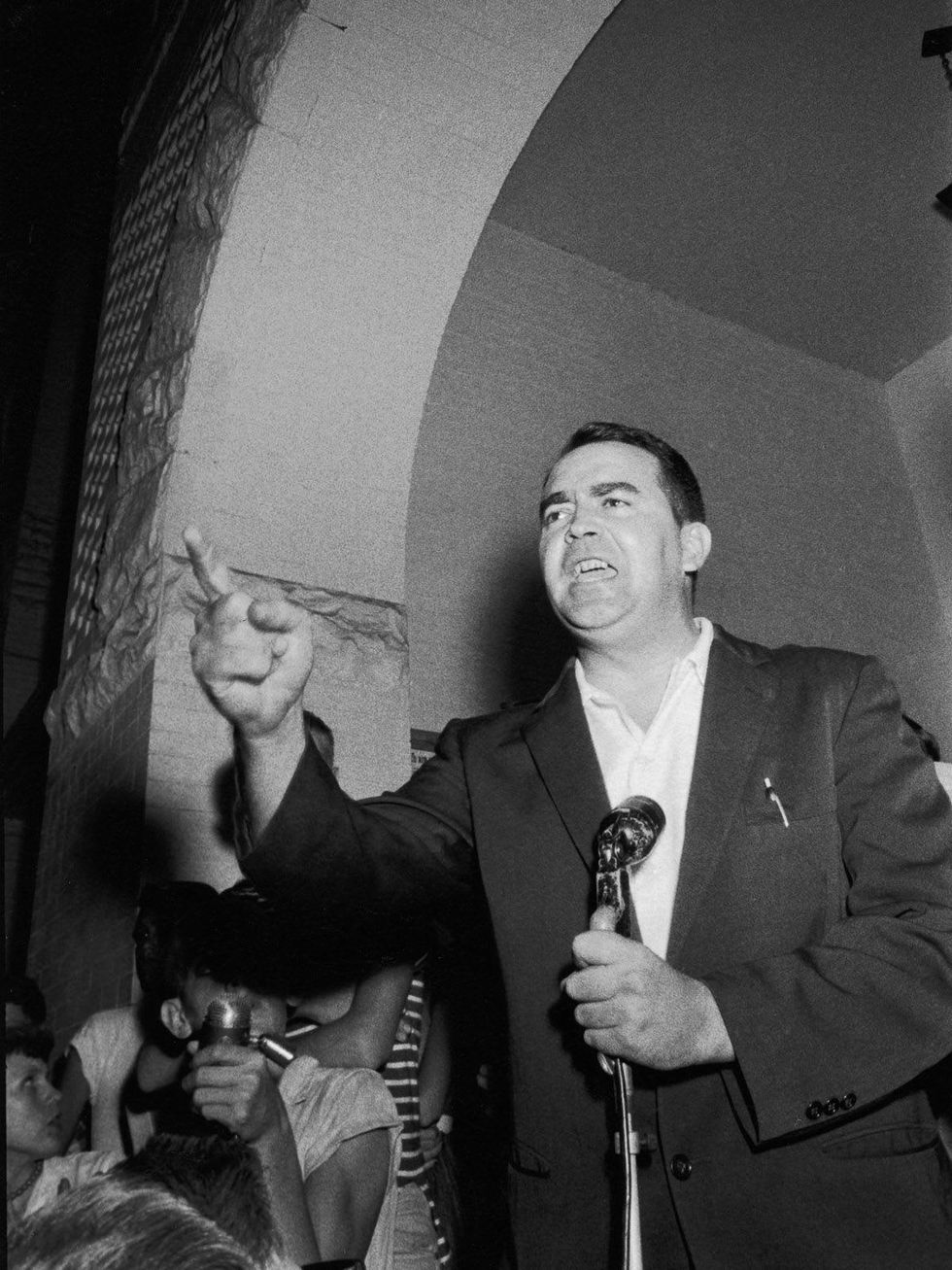

In the 1950s, Asa Carter had founded five chapters of the Ku Klux Klan, whose members brutally attacked black citizens throughout Alabama. As George Wallace’s speechwriter, Carter had penned the Alabama governor’s infamous “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” speech.

In fact, Carter’s racist beliefs were so extreme that in 1970 he split with his old boss, accusing Wallace of being “a sellout to the Negro.” Yet less than five years later he was on the Today show, being introduced by Barbara Walters to the American public as the “soulful and sensitive voice behind The Education of Little Tree.”

For editorialists across the country, the exposure of Forrest Carter was an occasion for soul-searching. And for Douglas and me, Carter’s story became the basis of a project that has consumed us for more than two years. Our collaborative effort, The Reconstruction of Asa Carter, is a feature-length documentary film about this charismatic, frightening — and perhaps completely transformed — man.

The Beginning

The Reconstruction of Asa Carter had its inception more than a decade ago, when Douglas and I we were introduced as Brandeis University students. Douglas’s thesis adviser and the third reader on my dissertation, put Douglas in touch with me when I was a grad student beginning to work on a project about ethnic impersonators — people who for one reason or another discard their birth identities and remake themselves in the guise of new ethnicities.

In an effort to get to know him, we needed to uncover layer upon layer of self-created fictions.

So, in spring 1993, I served as a talking head for Douglas’ thesis project, an extremely low-budget documentary film based on the strange story of Asa Carter, white supremacist-turned-Cherokee author.

Since his graduation from Brandeis, Douglas has spent most of his time producing documentary films for A&E, Discovery Channel, the History Channel and the independent production company Mouth Watering Media (a partner of CultureMap, which is helmed by CEO Stephen Newman, Douglas' brother). I went on to teach in the English and American Studies departments at Virginia Commonwealth University and now the University of Richmond and to write books, including Slippery Characters: Ethnic Impersonators and American Identities. I have also directed community-based oral history theater projects.

I was busy writing a new book about women and guns in spring 2004 when I got a phone call from Douglas, who was interested in producing a documentary based on Slippery Characters. Soon we decided to collaborate on a series of films about Asa and some of the other shifty characters from my research, and before I knew it I was working as writer and co-producer while Douglas produced and co-directed our first project.

To begin, Douglas and I partnered with independent filmmaker Marco Ricci to help develop the visual style and structure of the film. We agreed that what makes Asa — aka Forrest — so alluring is a deep sense of mystery.

In an effort to get to know him, we needed to uncover layer upon layer of self-created fictions. We believed that the visual style of the film should reflect Carter’s “slippery, layered truths” and should move seamlessly in and out of fact and fiction, past and present.

To help us bridge different eras, we developed a camera-mounting system that piggybacked an old- fashioned Super 8 film camera on top of a digital video camera. When we recorded, the two cameras picked up the same image and camera movement, allowing us to edit them together to create a seamless transition from a modern video aesthetic to an archival film aesthetic. This effect gives the sense of a memory taking the viewer back in time.

We also incorporated actual newsreel film from the 1950s through the 1970s in order to blur the line between fact and fiction. To connect different historical moments even further, we manipulated the color, temperature, and grain structure of the film to impart a timeless quality. Landscapes, archival photographs and film and original music by acclaimed producer and composer Pete Anderson contributed context and mood.

Using only minimal traditional narration (delivered beautifully by Texas songwriting legend Guy Clark), Douglas, Marco and I decided to have Carter’s story told largely in the voices of the people who knew him best, thereby providing unprecedented access into the life of this enigmatic man. We set out to meet and interview a range of fascinating people, including friends in Texas and Alabama, business associates from the publishing world and in Hollywood, and members of George Wallace’s inner circle.

The Journey

To place the story in its historical context, we also incorporated the reflections of scholars and historians.

In Montgomery, we spoke to Wayne Greenhaw, the Alabama journalist who had first exposed Forrest Carter as a fake after Carter’s 1975 interview with Barbara Walters (“Folks called me up and said, ‘I saw old Asa on the TV yesterday,’” Greenhaw explained). As we sat together on the gleaming marble steps of the Alabama State House, across the street from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. preached some of his most gripping sermons, Greenhaw recalled George Wallace’s 1963 inauguration and the part Asa Carter played in his political success.

The many years we have worked on this project have brought us down many deserted country roads and through a lot of airports and have left us waiting in coffee shops for interview subjects who never showed up.

In New York City, we interviewed Diane McWhorter, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Carry Me Home, who was able to paint a vivid picture of Alabama politics of the 1950s and 1960s and to recapture the shadowy cabal of violent racists who enforced the genteel system of oppression. Howell Raines, a retired executive editor of the New York Times and a Pulitzer-Prize winning author, shared stories from his life as a young reporter in 1950s Alabama, where Asa Carter had been founding White Citizens Councils and building his own chapters of the Ku Klux Klan — reportedly because he felt existing chapters were insufficiently extreme.

In Columbia, South Carolina, we spent a day in the law office of Tom Turnipseed, director of George Wallace’s 1968 national campaign. Turnipseed shared his memories of the days when Wallace was beginning to burst onto the national scene. He also spoke of the subsequent time when Wallace began distancing himself from embarrassing extremists like Carter who had been instrumental in building his political career. Turnipseed, now a personal-injury lawyer and former state senator, cried as he recounted his own conversion from segregationist to anti-racist activist.

We went to Abilene, Texas, to interview friends who knew Carter not as the Klansman he had been in a previous incarnation but as the Cherokee author of the best-selling memoir The Education of Little Tree.

In Cherokee, North Carolina, storyteller Owle spoke of The Education of Little Tree in the context of Cherokee narratives and traditions. Cherokee policy analyst Richard Allen, a member of the tribe's Eastern Band who we met in Oklahoma, holds a more hard-line opinion of Carter's ruse. He laments the author's reliance on established stereotypes of Native Americans to draw the reader in. His view of Forrest Carter is anything but sympathetic.

We passed a wonderful evening in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, with Rhoda Weyr, Forrest Carter’s agent, and her husband Fred Kaplan, who served us a delicious dinner in their house in the woods. The next day, Weyr narrated the hair-raising tale of the night Carter spent at her apartment — an evening that began with his casual use of a racial epithet to describe a worker in her apartment building and ended with her barricading her four young daughters in a bedroom following Carter’s crude passes at the 10- and 13-year-olds.

Weyr was able to place Carter in the context of the New York publishing world of the 1970s. Although he appeared naïve, she said, “he played us all very effectively.”

This was the conclusion as well of Bob Daley, the producer of The Outlaw Josey Wales, the acclaimed Clint Eastwood movie based on Carter’s first novel. Daley, a legendary producer who spent fifty years working in the film industry, painted a portrait of Carter as a man who offered him great comfort during the months when Daley’s father was dying — but who was also capable of sending Daley a vituperative letter full of anti- Semitic and racist slurs.

The many years we have worked on this project have brought us down many deserted country roads and through a lot of airports and have left us waiting in coffee shops for interview subjects who never showed up. Yet they have also allowed us to understand more and more about this peculiarly American story of race and reinvention. Carter’s story illustrates not just American schizophrenia about race — but also the mutability of American identities. The Reconstruction of Asa Carter asks not just how Carter could be two people at once, but also why so many Americans, both Carter’s circle of intimates and the hundreds of thousands of Forrest Carter’s fans, fell in love with his portrayal of his Cherokee self.

With three decades of historical perspective, The Reconstruction of Asa Carter explores important questions about identity, race and racism, and the powerful American tradition of self-creation. It asks what it is about American discourse that makes us accept such persons so readily — and then feel so betrayed when their deceptions are exposed.

The film examines the unique way in which a “fictional memoir” like Little Tree stands as a monument to the tradition of American self-invention as well a testament to the porousness of ethnic identity. Fake Indian autobiographies continue to appear, often to great acclaim.

In fact, Little Tree is one of a long line of these memoirs, which have been literary successes in the United States for over a century. Carter’s story has much to tell us about the South during the civil rights movement, about Carter’s personal journey, and about the complex process of creating art. Yet the The Reconstruction of Asa Carter is much more than a biopic.

Ultimately, we want to leave viewers with a perspective on the fake ethnic autobiography as a genre, so that the next time a literary scandal of this sort erupts, they will be able to see the faux ethnic memoir as a uniquely American genre — and one which can shed light on the complexities of American identity.

Our question, finally, is not how Asa changed, but how his story has the potential to change all of us — to help us fall out of love with stereotyped depictions of ethnic Americans, and to lead us to embrace the complex realities of race and ethnicity in America.

Laura Browder, Ph.D., is the Tyler and Alice Haynes professor in American Studies at the University of Richmond.