From Whitney to the Menil

The writing's on the wall at Steve Wolfe exhibition

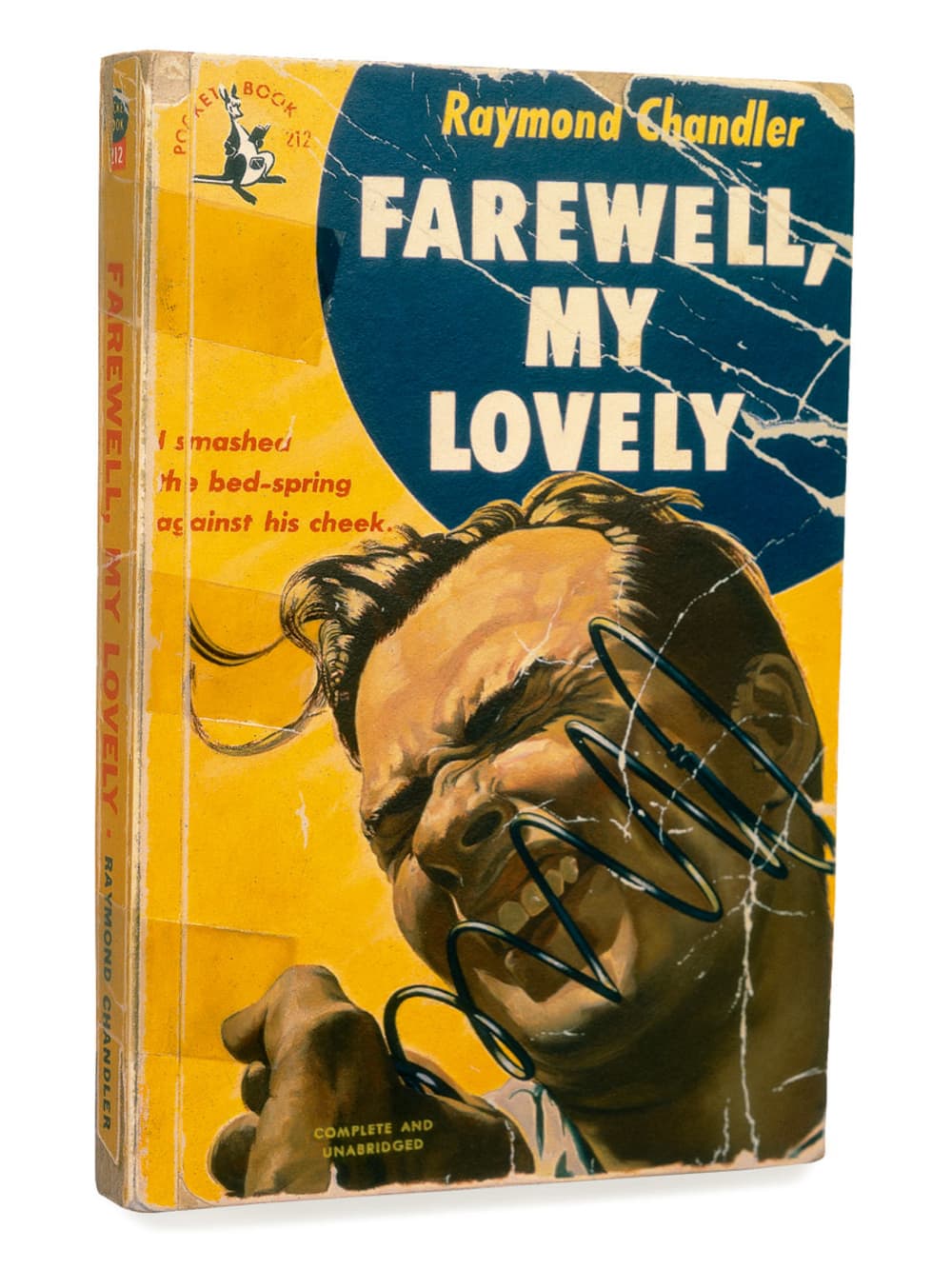

Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Farewell My Lovely), 1996, The Menil Collection, Houston,Bequest of David Whitney, ©2009 Steve Wolfe

Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Farewell My Lovely), 1996, The Menil Collection, Houston,Bequest of David Whitney, ©2009 Steve Wolfe Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Study for Mumm/Jose Cuervo Cartons), 1994, Collection ofLawrence Luhring, ©2009 Steve Wolfe

Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Study for Mumm/Jose Cuervo Cartons), 1994, Collection ofLawrence Luhring, ©2009 Steve Wolfe Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Study for Mosquitoes), 1999, Collection of Gail and TonyGanz, ©2009 Steve Wolfe

Steve Wolfe, Untitled (Study for Mosquitoes), 1999, Collection of Gail and TonyGanz, ©2009 Steve Wolfe Steve Wolfie, Untitled (Do You Believe In Magic?), 1992, Collection of James andDebbie Burrows, ©2009 Steve WolfePhoto by Anthony Cunha

Steve Wolfie, Untitled (Do You Believe In Magic?), 1992, Collection of James andDebbie Burrows, ©2009 Steve WolfePhoto by Anthony Cunha

In his book, The Accidental Masterpiece: On the Art of Life and Vice Versa, New York Times chief critic Michael Kimmelman commands the reader to "elevate the extraordinary" with a profile of an eccentric who accumulated books in a tiny Manhattan studio. So meticulous was this friend that once his bookshelf-lined walls were filled, he threw out a book of equal size in order to introduce a new one — a statement on neurosis and literary devotion, "representing what he regarded as beautiful in the world." Although it was only an individual's library, Kimmelman likens the apartment to an "aesthetic and heartfelt expression."

With the same literary diligence of Kimmelman's companion, artist Steve Wolfe reconstructs dog-eared books, studies of which are spotlighted in the latest Menil Collection exhibition, "Steve Wolfe on Paper."

"I would consider myself a very literary person; I originally intended to be a writer, and then got sidetracked," Steve Wolfe said during a recent interview. He spoke with an earnest grin - this isn't a bookish pseudo-intellectual putting on airs, but rather an artist generously telling the story of a life among books - a man devoted to elevating the extraordinary.

Wolfe has won acclaim by creating hyper-realistic sculptures of "classic" novels. As is to be expected of the Menil, curator Franklin Sirmans and Whitney Museum curator Carter Foster have taken an alternative approach to displaying an artist's process by focusing on Wolfe's works on paper, some purely drawn but most combining aspects of drawing, painting, collage and printmaking. The resulting exhibition reveals a particular individual's menagerie of written works and vinyl records. In an instant, an unimposing museum gallery becomes the crossroads of personal history and material memory.

Fittingly, Wolfe chose a warm linen hue to offset the small exhibition from Renzo Piano's stark white interior, establishing an intimacy appropriate for displaying a personal library. The show begins with two studies of sketchbook drawings; that is, graphite pencil drawings of sketchbooks to be later constructed as aluminum sculptures. By simply examining the frail notebook spiral holding the covers together, the viewer may begin to grasp the acuity of Wolfe's hyper-realistic technique. It is also at this first gesture that the personal-private dichotomy is manifest: the closely guarded object of the artist's sketchbook stands naked on the wall, yet the interior is turned against the gallery, tempting the viewer with an innocuous, gray art store staple. These almost minimalist nuanced drawings act as the exhibition's spark, inculcating Wolfe's obsession with the depiction of surfaces.

A collection of reconstructed book covers makes the bulk of the exhibition. Several are studies for "carton pieces" – sculptures made of acid-free archival cardboard that Wolfe painted on a wall, incised and assembled to look like genuine cartons carrying books. Each "carton" holds a top layer of arranged "books," which are in actuality just a layer of paper with meticulously reconstructed book covers. It is the studies for these top layers that capture the viewer's attention at the Menil.

Other than the carton studies, individual book covers are on display – the beginning stages of three-dimensional reconstructed books. Scanning the gallery is like reading a 1960s bildungsroman; covers of Jack Kerouac's On the Road, Surrealist manifestos and old school British lit speak of a sincere intellectual coming of age in the decade that witnessed the twilight of modernism. The upper section of Untitled (Study for Chock Full of Nuts/Sinatra/Brown Ale Cartons) features a recreated back cover of a mid-'60s MoMA Jackson Pollock exhibition catalog. Here is an iconic artist (Pollock), whose work is exhibited at a museum, which is documented in an exhibition catalog, then meticulously re-represented by Wolfe.

The resulting image could be classified as something like "meta-cubed," but just as he eschews such categories as "Pop" and "hyperrealism," Wolfe prefers not to be pigeonholed. And although most of his recreated book covers date from what he considers the golden age of book design, the '60s and '70s, the selection is more self-referential than attempting to capture the zeitgeist of a turbulent era. In the highly personal Untitled (Study for Mumm/Jose Cuervo Cartons), Wolfe includes a reconstructed cover of a children's bird-spotting guide. To retrace his childhood ephemera, he had pages of the book photographed and located old art-grade paper upon which he had text from the bird book silkscreened. What looks to be Scotch tape buttressing the ragged volume is in fact oil paint coated in varnish.

The exhibition, which premiered at New York's Whitney Museum last September, has been augmented in Houston with six additional fully-realized book sculptures, a gift from late Menil board member David Whitney (no relation to the Whitney Museum). The books are made of wood, paper and modeling paste, an acrylic polymer similar to spackle. Linen and cardboard form the spine. To create the book covers, Wolfe used woodblock printing on paper, which was sanded to create a "skin" and then laminated onto the woodblocks; the book covers' text is usually silkscreened. The inclusion of these complete sculptures brings Wolfe's artistic process full circle, from study to finished work.

A selection of recreated vinyl records complements the pithy array of books. "To make these albums, the enamel is taped off and I lay down layers and layers of it until it forms a lip so that there is an illusion of depth," Wolfe explained. The records' grooves are made with a chopped-off paintbrush jammed into a large wooden compass. He even measured the precise distance between the bands separating the songs. If Wolfe's albums were held next to the real thing, the disparity would be apparent, but the falsified Velvet Underground and Lovin' Spoonful records resonate with a personal memory that is more poignant than any prepackaged tangible icon.

It would be all too easy to draw conclusions about Wolfe's work: that he is memorializing a youth lived with intellectual authenticity or mourning the loss of the tangible written and musical work in a digital age. But Wolfe is no nostalgia-churning Luddite: "I'd use a Kindle if somebody showed me how to work one," he said.

Despite its personal subject matter, Steve Wolfe on Paper will be, more than anything, relatable to museum visitors. Sirmans notes, "For Wolfe, it is not just the representation of the information the book conveys, but it is the reader's involvement with the object." Indeed, a book tells two stories – the original writer's plot, and the reader's experience: spotting a vintage volume in a used bookstore, the ocean splashing saltwater upon starched pages, forgetting a novel on an airplane. Through this collection of more than 30 precious works, Wolfe writes his own lifelong literary sojourn.

"Steve Wolfe on Paper" is on view April 2 - July 25. A panel discussion and opening reception will be held Thursday, April 1, at 6 p.m.