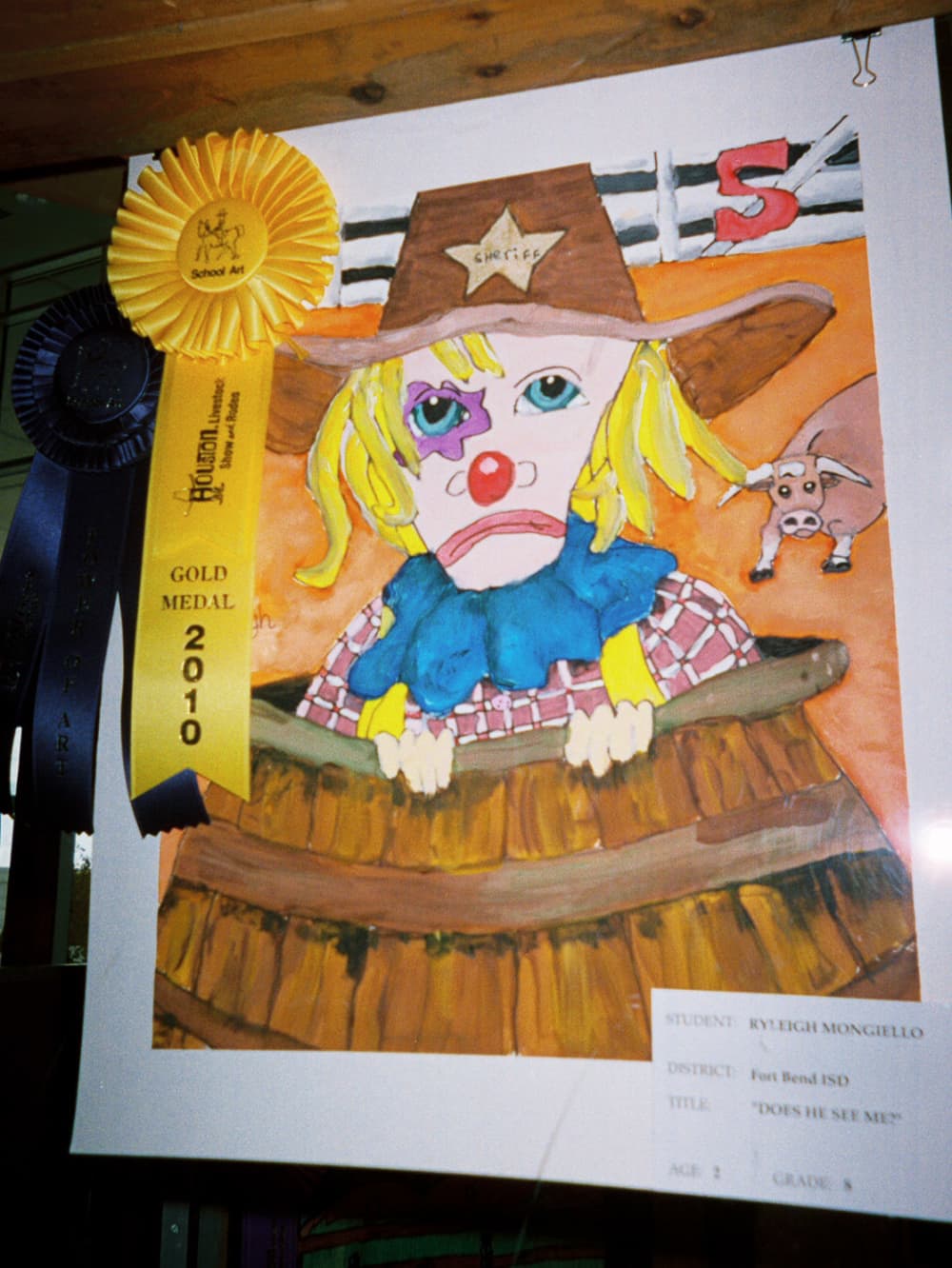

At Reliant Center, I found this exhibit of children’s artwork on display. Onepainting that pulled me in was “Does He See Me” by Ford Bend ISD second-graderKyleigh Mongiello.Photo by Katie Oxford

At Reliant Center, I found this exhibit of children’s artwork on display. Onepainting that pulled me in was “Does He See Me” by Ford Bend ISD second-graderKyleigh Mongiello.Photo by Katie Oxford I got nose to nose with a horse painted by a third-grader. The title read“GOLLY,” which I’d call not only GOOD but GREAT.Photo by Katie Oxford

I got nose to nose with a horse painted by a third-grader. The title read“GOLLY,” which I’d call not only GOOD but GREAT.Photo by Katie Oxford I fired off a few shots with my camera of "Hall A" and moved on to “Hall B,”which held cattle and, for a little while, me.Photo by Katie Oxford

I fired off a few shots with my camera of "Hall A" and moved on to “Hall B,”which held cattle and, for a little while, me.Photo by Katie Oxford “Why are you doing that?” I asked genuinely of a man wearing a cap. The manwiped his mouth and said curtly, “Just cleanin' him up.”Photo by Katie Oxford

“Why are you doing that?” I asked genuinely of a man wearing a cap. The manwiped his mouth and said curtly, “Just cleanin' him up.”Photo by Katie Oxford

I’m an animal advocate and the only ones I eat (on occasion) live in the ocean so the likelihood of me going to a rodeo is sorta similar to something my grandfather used to say, “Honey child, you’re tryin’ to get a poodle out of a hound dog.”

But last Saturday, I put my PETA sign down and my dusters on and spent the day rooting around the rodeo, set on keeping an open mind, an open heart and finding something I could enjoy. And guess what? I did, almost immediately.

I entered at Reliant Center and found an exhibit of children’s artwork on display. Then I found a chair to climb on for a better look and my, what a view!

I got nose to nose with a horse, painted by Paul Ramos, a third-grader from Clear Creek ISD. The title read “GOLLY,” which I’d call not GOOD but GREAT. “GOLLY” is the head of a horse with eyes looking straight (or rather not so straight) at you with a background the color of overcooked corn on the cob. I chuckled, thinking “this horse’s expression is exactly how I FEEL when P and I are having a heated argument.”

“Goatee,” painted by Rachel Willeford, a sixth-grader from Cedarview ISD, also grabbed me. This is a goat with a captivating gaze looking at you through horse wire. If you don’t yearn to reach through the wire and touch this animal then you might want to have your heart examined.

Another painting that pulled me in was “Cowboy at Sundown,” by Andy Carrico, a fourth-grader from Huffman ISD. Wearing a red shirt and hat, this cowboy’s looking at you and seemingly THROUGH you. You get the sense that he’s completely at peace with himself and the planet ... the variations of red are luscious.

I could’ve spent the day in this one spot and, in retrospect, probably should have, but instead, I continued through the corridor, where I noticed the same signage at nearly every archway.

“AGRICULTURE*EDUCATION*ENTERTAINMENT*WESTERN HERITAGE”

“Each year, nearly 350,000 youth competitors participate in the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo”

“Since 1932, ‘the Show with a Heart’ has awarded more than $105 million to junior show exhibitors and other youth participants, and since 1957 has committed more than $130 million to scholarships and direct educational support.”

“Also since 1932 the world’s largest livestock show and rodeo has hosted more than 1 million livestock and horse show entries and more than 55.3 million spectators.”

It was something in the second, “The Show with a Heart,” that tweaked my interest. I inquired about this to an official nearby, and he politely directed me to the “Press Room, 2nd floor, room 500.” So off I went.

The woman in the press office couldn’t have been nicer. She didn’t know the origin of “The Show with a Heart,” nor who first used it. “But let me check on that,” she said, “and I’ll give you a call.”

I realized, though, that if I was going to see the rest of the rodeo, I couldn’t get stuck on heart stuff. I thanked the woman and told her “no big deal, just curious.”

Back in the corridor, I took a deep breath and entered “Hall A,” which held chickens, turkeys, goats, rabbits, sheep and the pony ride. I didn’t stay long. I fired off a few shots with my camera and moved on to “Hall B,” which held cattle and, for a little while, me.

I heard the sound before I saw him. A man wearing a cap stood over a young white-faced Hereford cattle running electric shears just above his spine — from rump forward. The animal’s eyeballs appeared as though they were about to pop out of his head. Although his muzzle was tightly harnessed and tied to an iron bar with another rope tied from a thick ring in his nose, his feet moved nervously. The shearer reached over and pulled downward on one of the ropes. The Hereford’s eyes rolled back further — now looking almost completely white.

“Why are you doing that?” I asked genuinely.

The man wiped his mouth and said curtly, “Just cleanin' him up.”

“What’s his name?” I quietly inquired. The man said nothing.

“What’s his name?” I asked again.

“He dudn’t have a name,” he answered, stepping back and taking a spit.

I then tried speaking to No Name using soft sounds, trying something however small that might alleviate his obvious terror, but I was as harnessed as he was. So I stood — as still and as silent as I could be — with No Name, until about five minutes later I could be there no more.

“Time to go home,” I thought.

I went outside, into the sun and walked slowly back to my car holding the white-faced Hereford heavy in my heart.