Open to interpretation

Red & black, fact & fiction: Kate Rothko Prizel and Gregory Boyd search for thereal Mark Rothko

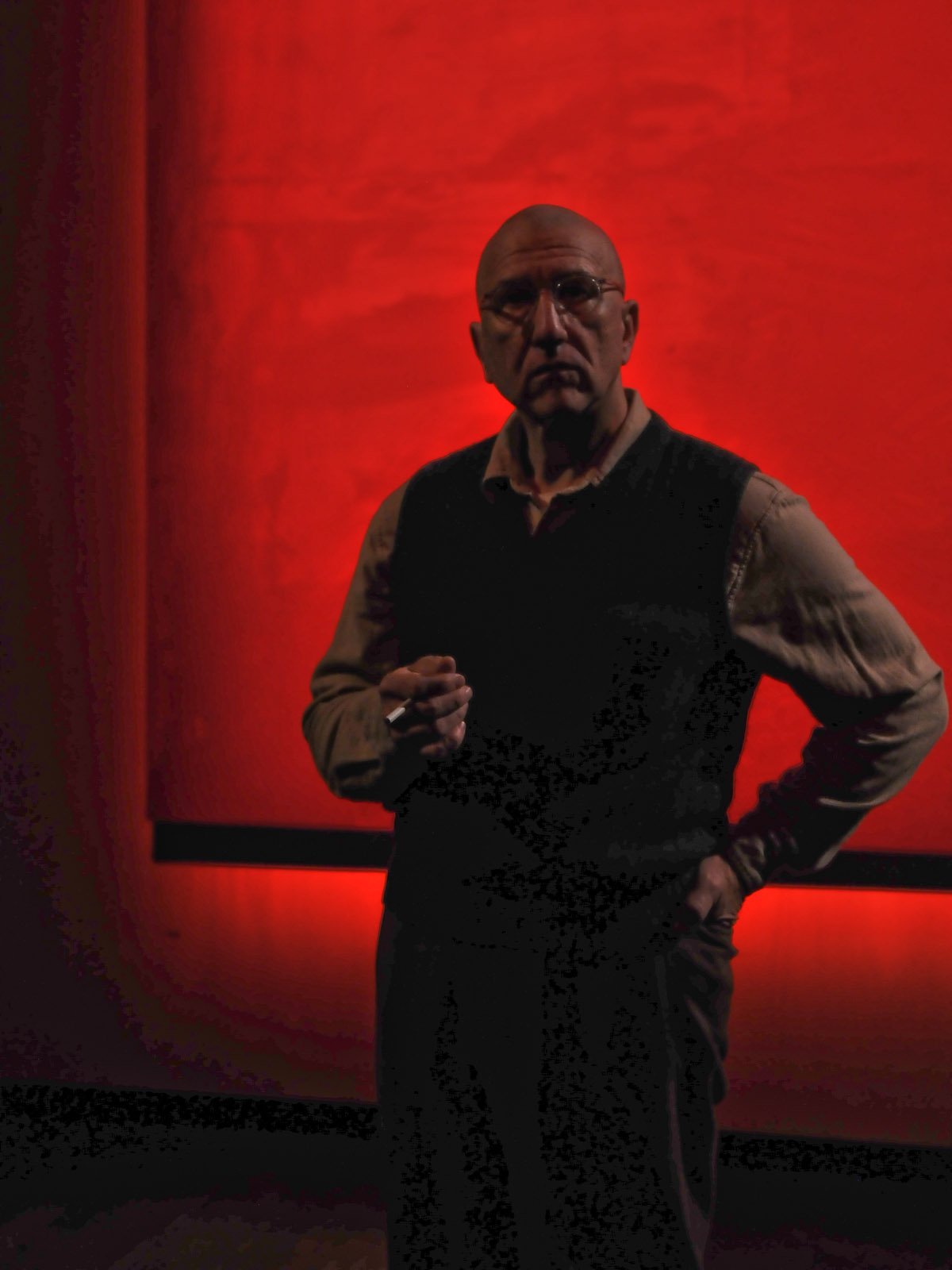

Scott Wentworth as Mark Rothko in the Alley Theatre's production of RedPhoto by Jann Whaley

Scott Wentworth as Mark Rothko in the Alley Theatre's production of RedPhoto by Jann Whaley Artist Mark RothkoNew York Observer

Artist Mark RothkoNew York Observer Kate Rothko Prizel, from left, Gregory Boyd and Terrence Doody

Kate Rothko Prizel, from left, Gregory Boyd and Terrence Doody

What happens when visual arts, dramatic arts, and the real life of a great artist clash? That was one of the difficult subjects examined Monday night at the Rothko Chapel during the special program “Fact, Fiction, and Interpretation: Conversations about Red.”

In an event that itself could have been the subject of a fascinating play, Terrence Doody, Rice University English professor and the event’s moderator, Alley Thetre artistic director Gregory Boyd and Dr. Kate Rothko Prizel, the only daughter of Mark Rothko, came together to discuss playwright John Logan’s Tony Award winning play Red.

Now in production at the Alley Theatre, Red is directed by Jackson Gay and depicts two years, 1958-1959, in the life of master abstract expressionist, Mark Rothko, as he works to complete the Seagram Murals, a series of paintings commissioned to hang in the Four Seasons Restaurant in New York. The play takes place entirely in Rothko’s studio and the only other character onstage is Ken, Rothko’s assistant, a character of Logan’s own creation.

For Prizel, the play depicts a character named Mark Rothko who is very different from her father.

Sitting amid the paintings of Mark Rothko in the Rothko chapel, a capacity crowd listened in Prizel, Boyd and Doody voiced their own interpret of John Logan’s artistic creation, the character Mark Rothko.

Prizel had several praises for the play, saying “As a drama this is, I think, an incredibly strong piece.”

She also noted that Logan “has in many ways created very vividly the kind of struggle my father was going, through perhaps not so much specifically at the time that series of murals was made. . .”

She takes some issue with the time setting of the play, however. Though Prizel believes the play takes “justified” artistic license, she is not certain that the audience will be aware that many of the broader artistic issues brought up in the play were not happening at this point in Rothko’s life and career.

Prizel was blunt about other concerns she has with the play’s depiction of her father. “I think the biggest problem I had with the play is I really don’t think that the author is interested in my father as a character. I think he was interested in creating drama, interested in dealing with the philosophical questions, but didn’t really make the attempt to learn what my father was like as a human being,” she said.

For Prizel, the play depicts a character named Mark Rothko who is very different from her father. “In many ways the play takes the humanism and humanity out of my father,” she said.

Prizel believes this lack of humanity in the fictitious Rothko is exacerbated by the created character of Ken. “In a way the assistant is presenting another side of my father’s own thought process, but by having that taken out of his mouth, it in some ways detracts from the humanity of my father,” she said.

Boyd understood much of her objections but believes that Logan has actually created only one character onstage and that the assistant Ken is an “aspect or dream” of Rothko. Doody interprets Ken differently as perhaps a stand in for Logan himself who is struggling to understand Rothko. (Logan first saw the murals at the Tate Modern in London when he was working on the screenplay for Tim Burton’s version of Sweeney Todd.)

Boyd understood much of her objections but believes that Logan has actually created only one character onstage and that the assistant Ken is an “aspect or dream” of Rothko.

Boyd adding to that thought, said, “There’s no question the play is centrally about the relationship between a master and a protege, between a teacher and a student, between a father and a son. . .”

The idea that the characters of Rothko and Ken have a type of father/son relationship in the play was brought up several times during the discussion. At no point did anyone on the panel pause to comment on the oddity of discussing the thematic implications of a parental relationship between the play’s version of Rothko and the fictitious Ken with the real life daughter of the real Mark Rothko.

Another problem Prizel has with the play its interpretation of the meaning of the color red and that Red, the play, portrays Rothko’s movement from red to a darker palette as a movement towards his decline.

“One of the things I found troubling is the emphasis on black taking over red. . .The inevitable interpretation is that as his paintings get darker they reflect the end of life, depression, and not only that but the end of an artistic career. I don’t see how we can understand that when we sit here in the Chapel. These paintings are incredibly dark but they were the beginning of something new. In many ways they were the culmination of my father’s career,” she said.

She went on to explain that years of studying her father’s work and trying to step back and be objective about that work has taught her that “to associate the darker palette with what was going on for him in his private life, his psychological makeup, whatever, is really a mistake.” She thinks the movement to a darker colors was a reawakening in her father’s work. The Rothko Chapel paintings, surrounding the proceedings, may attest to that idea.

Towards the end of the event, Boyd made the point that while a playwright might have more responsibility for accuracy when depicting a real contemporary figure, we shouldn’t look to Shakespeare for the true Richard III nor Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus for the real Mozart and Antonio Salieri.

So does Red give insight into the real Mark Rothko and his creation of the Seagram Murals or does it instead give insight into the real John Logan and his reaction to those paintings and their creation? In the end, like all great art, the audience must interpret for themselves.

Red runs through March 25 at the Alley Theatre. The Rothko Chapel is open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., as always.