Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke has set himself a tall order with The White Ribbon. His film attempts to do nothing less than explain the origins of fascism.

The austerely beautiful, black-and-white film is set in a Protestant northern Germany village in the months preceding World War I. Everything looks normal at first. The pre-war social order is firmly in place, with the Baron at the head of local social pyramid, the doctor and Lutheran minister below him, a teacher below them, and a bunch of impoverished farmers at the pyramid’s wide bottom.

Still, we learn right away that something is amiss in the unnamed village. The story is being told by an old citizen (Christian Freidel) who was the teacher there. Years later, after all the wars, the former teacher (few of the adults are named) is still puzzling over a series of unsolved crimes that were committed back then. The film begins with the town doctor (Rainer Bock) being injured in a fall from his horse. The fall was caused by a wire hung apparently intentionally across his riding path. Shortly thereafter, a woman dies in what may or may not be a work accident. The Baron’s son is kidnapped and tortured.

This incident enrages the Baron, upon whose good will the village absolutely depends, and he warns the townspeople not to protect the dangerous criminal they apparently harbor in their midst.

But, despite this being a nosy and gossipy village, no one seems to know who’s committing the crimes, so, Kafka-like, suspicion falls on everyone. Haneke gradually moves his camera inside the villagers’ homes. There we find a good deal of bad behavior by the adults, but it’s the kind of nastiness that was accepted as normal in the rigid, sexually repressive, male-dominated society of the day. The minister ties his son’s arms to his bed so the son won’t be tempted to masturbate under his covers. The doctor probably would’ve been considered a monster even then—he sexually abuses his own daughter and verbally abuses his mistress (his wife is dead) in terms that are quite chilling. The Baron exploits the peasants.

And so on. Only the teacher and his young fiancée (a mercifully charming Leonie Benesch) are people you wouldn’t cross the street to avoid meeting.

Haneke has cunningly laid out his indictment. While villagers and audience alike are wondering who tortured a young Down’s syndrome boy to the point of nearly blinding him, a close but almost incidental look at the adults’ (or the men’s, to be more precise) behavior shows the audience, with almost clinical precision, that a sickness of the soul was abroad in the land.

If you’re of the Guns of August school of history, and think that if the European leaders had just made better decisions in the buildup to WWI, the whole debacle (and Hitler himself) could’ve been avoided, Haneke disagrees. He argues here that fascism was deeply planted in the culture, just waiting to emerge.

It appears (though it’s never made crystal clear) that it’s the children of the village who are committing the crimes. And this same generation of children grew up to be Nazis. But it’s not just that the kids were bad seeds. According to Haneke, their parents planted them in barren, much abused soil.

Haneke makes a strong case. We know, for example, that Hitler’s father was much like the fathers here. Of course this doesn’t excuse Hitler for his crimes, but the film does offer a context and a partial explanation.

Despite its interesting ideas, however, The White Ribbon isn’t always gripping. Haneke’s evidence-gathering pace will be too slow for many. And he doesn’t offer any sort of resolution. But the lack of answers may be why the film lingers in the mind, becoming more interesting once you’ve left the theater and started

The show has plenty of dancers strutting their stuff.Courtesy of Hulu

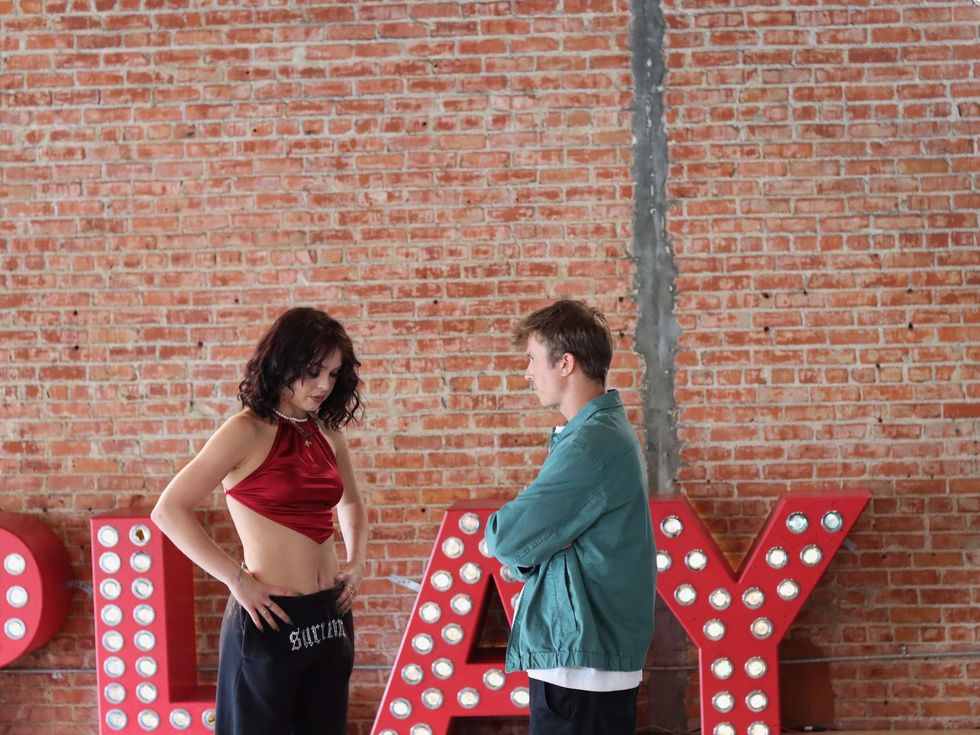

The show has plenty of dancers strutting their stuff.Courtesy of Hulu Dancers Madison Cubbage and Kenny Wormald discuss something spicy.Courtesy of Hulu

Dancers Madison Cubbage and Kenny Wormald discuss something spicy.Courtesy of Hulu