Medical Breakthroughs Happening in Houston

Fighting sudden death: UTHealth's Dr. Dianna Milewicz is isolating the genesthat killed John Ritter

Dr. Dianna Milewicz has been studying thoracic aortic dissections for 10 years,and has identified four genes linked to the disease.

Dr. Dianna Milewicz has been studying thoracic aortic dissections for 10 years,and has identified four genes linked to the disease. Actor John Ritter's family his teamed with UTHealth for a public awarenesscampaign about thoracic aortic disease called Ritters Rules.Photo by Robert Trachtenberg/ABC

Actor John Ritter's family his teamed with UTHealth for a public awarenesscampaign about thoracic aortic disease called Ritters Rules.Photo by Robert Trachtenberg/ABC Genetics is the ultimate form of preventative medicine. Dr. Milewicz and herteam hope to identify more than 50 percent of the associated genes in the nextfive years.

Genetics is the ultimate form of preventative medicine. Dr. Milewicz and herteam hope to identify more than 50 percent of the associated genes in the nextfive years.

Houston's Texas Medical Center has long led the way in surgical advances and, now, it's blazing trails in genetics.

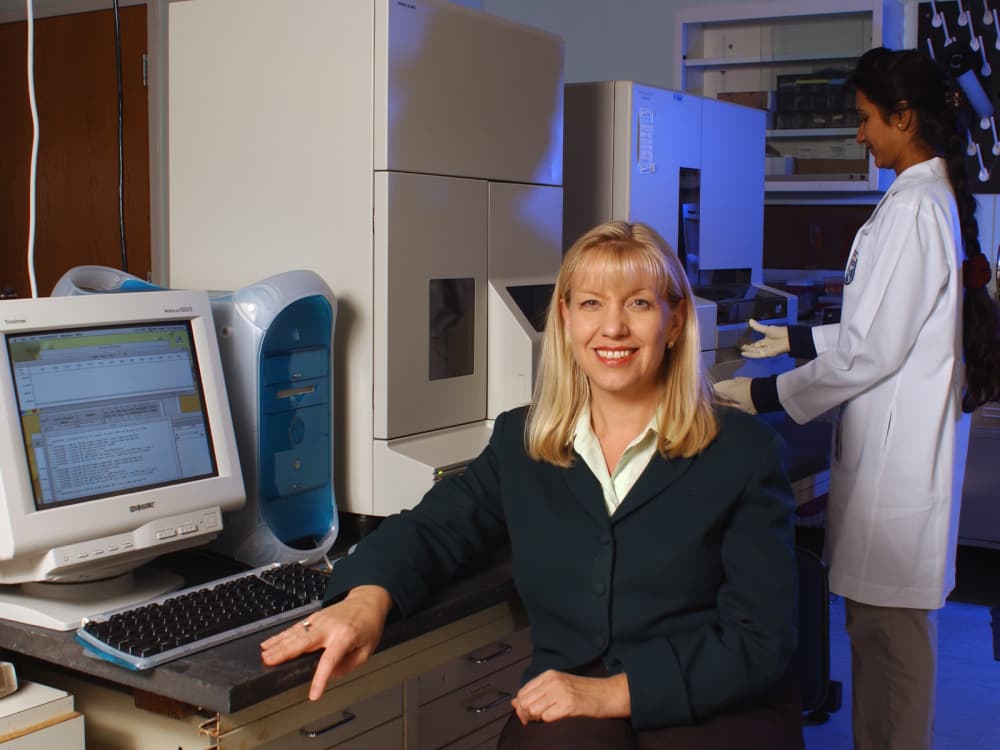

"Genetics is preventative, and it's personalized," says Dr. Dianna Milewicz, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chairman of the Division of Genetics at The University of Texas Health Science Center (UTHealth). For a decade, Milewicz has been studying, isolating and sequencing genes that cause thoracic aortic dissection — the disease that suddenly killed the actor John Ritter.

Ritter's family has since joined Milewicz in launching a public awareness campaign about thoracic aortic disease (TAD), called Ritter Rules. TAD occurs when the wall of the aorta, the major artery that takes blood away from the heart, weakens — forming an aneurysm or bulge. This aneurysm can ultimately lead to a dissection, or tear in the aorta, which can be fatal.

"The aorta is under constant force, like an oil well," Milewicz explains. "It needs to stand up to a lifetime of pressure, and if you don't repair it, it can rupture and cause a dissection, which only 50 percent of people survive."

Milewicz and her team have now successfully identified four genes linked to TAD, allowing patients with a family history of the disease to be screened for internal symptoms before suffering a life-threatening complication. As a result of their work, John Ritter's brother was able to have his aneurysm surgically repaired before it dissected, likely saving his life.

Milewicz says it took four years to identify the first and most frequently occurring gene, Smooth Muscle Alpha-Actin (ACTA2), which is responsible for 10 to 15 percent of the inherited from of TAD. This mutation in smooth-muscle actin causes what is essentially muscular dystrophy of the aorta. Milewicz's team found the most recent gene in just eight months.

"It's getting quicker. We should find more than half of the genes that cause this in the next five years," Milewicz says, largely due to the number of families that are flocking to participate in her study. Twenty families helped isolate the first gene. Around 600 are participating now.

I spoke to one of Milewicz's early participants, 62-year-old Pat Arthur — a Houston native who had his aortic arch replaced after coming up positive for a genetic mutation. A cousin had gotten in touch about their family history — of Arthur's 10 aunts and uncles, half died of aortic aneurysms, as had his father.

An avid diver and father of a 14-year-old daughter, Arthur says he's not certain he'd be around if he weren't involved in Milewicz's study.

"It extended my life incomparably," Arthur says. He had surgery in 2006 and is headed to Palau next summer to dive with his wife and daughter, who gets to pick their travel destinations when she makes all A's.

"I can't say enough about (Milewicz) or my cousin," Arthur says. "If I hadn't been involved I probably wouldn't be here."

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook