TATTERED JEANS

Battling bullies and learning courage from the brother who took a beating

Sometimes, it's the guy in the lab coat with a medical degree who wants to bullyyou.

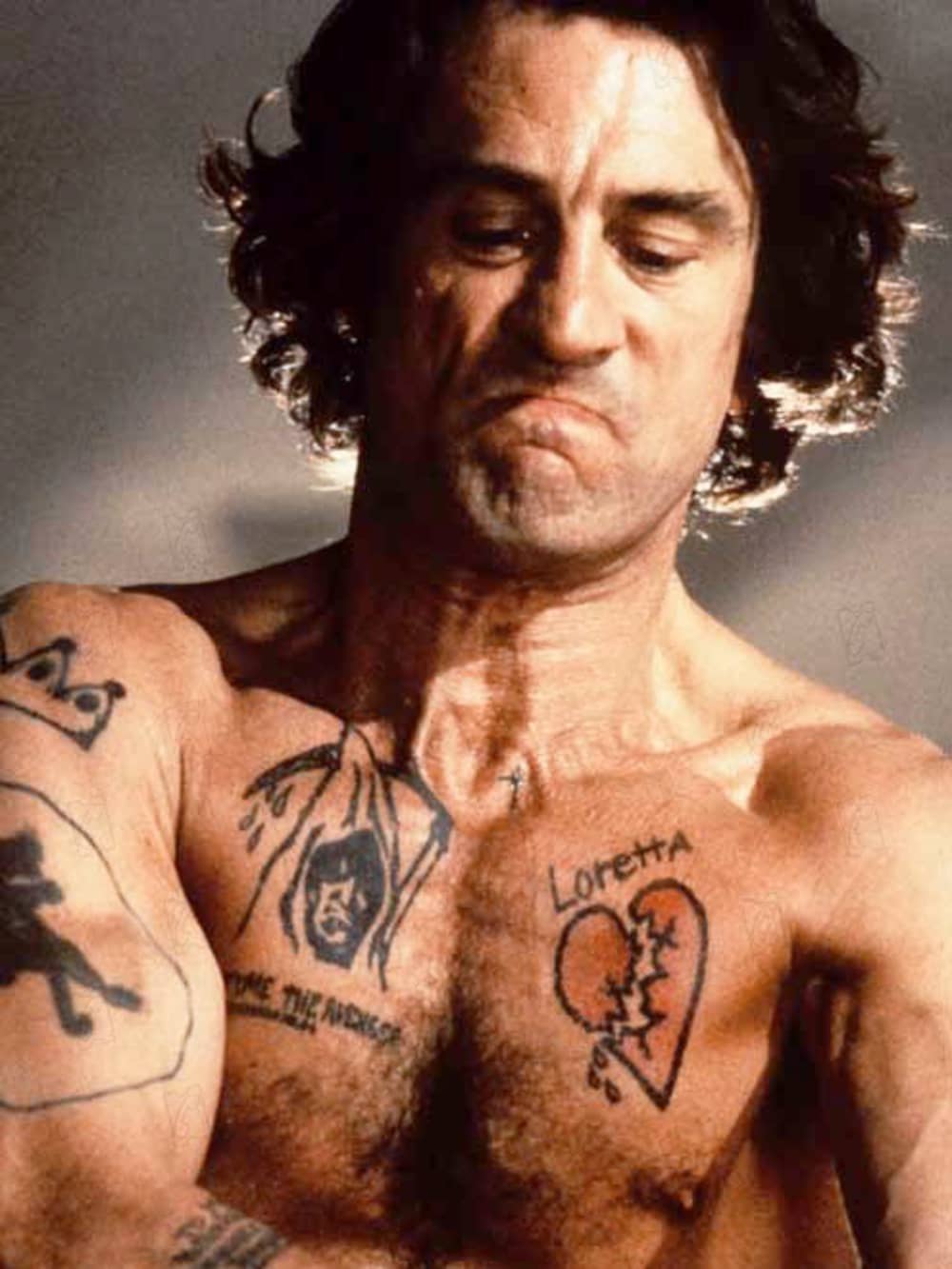

Sometimes, it's the guy in the lab coat with a medical degree who wants to bullyyou. Robert De Niro's character in Cape Fear was another violent bully.

Robert De Niro's character in Cape Fear was another violent bully. Katie's brother Kit used to kiss her like Bugs Bunny smooched Elmer Fudd whenthey were toddlers.

Katie's brother Kit used to kiss her like Bugs Bunny smooched Elmer Fudd whenthey were toddlers.

My mother had fought a 15-month battle with ovarian cancer. Now, a layer of mucus dulled her hazel eyes as she lay in a hospital bed full of morphine and unable to speak.

The day before she died her oncologist came knocking on the door wishing to take her, “downstairs,” for something, “experimental.” I vetoed the plan. Dr. Ritter bristled and countered with a one two punch.

“Katie how would you feel if you found out later that we could’ve done something more for your mother? Could you live with that?”

Fear and doubt poured into my stomach like an avalanche and I felt my face flush. My mind, however, was unchanged. With his hands still in the pockets of his white starched coat, Dr. Ritter pressed on, demanding to know where my father was and when he was expected to return.

“Very well,” Ritter said. “I’ll be back!”

I took a chair from mother’s room and placed it in the hallway where Dr. Ritter had stood. Then I sat in it. I would sit in that seat waiting for my father to return and recall how my brother had once sat in his, 16 years before.

Bravery in a brother

There was a bully in high school who rode on the same school bus with my brother, Kit, and me. His name was Mike Ellis. He had black wavy hair and squinty eyes, a Robert De Niro look-a-like in the movie Cape Fear only shorter.

Mike was more than mean. He was cruel. In the halls, he ruled, shoving anyone in his path. If he saw someone carrying an extra load of books he took great pleasure in making them fall. I often saw him tangled up in a fight, which he’d pick and to my knowledge, never lost.

As toddlers, Kit used to kiss me like Bugs Bunny kissed Elmer Fudd. When we got a little older, he’d sometimes sock me in the stomach.

By high school, there was 20 yards between us as we walked from the car to the school building but I always knew that from the corner of his eye, Kit watched over me. He cared. He played football for the high school team, wore his blue FFA jacket proudly, and worked part time at a veterinary clinic. He was good looking, quiet, and liked by just about everyone. I adored him.

One hot afternoon while riding home on a jam-packed bus, Mike approached my brother, who was sitting in an aisle seat, three rows behind me.

“GET up!” Mike demanded. “I want that seat.”

I turned and saw Kit looking up at him like he’d been hit with a cattle prod. “This is my seat,” my brother said. Then he looked toward the front again and with a quiet but steady voice said, “I’m not MOVIN’.”

No one did. All eyes except the bus driver’s looked at my brother and Mike Ellis. In a second, Mike slammed his right fist into Kit’s face. Blood and books flew in all directions. I stood up with the urge to run back there but I didn’t budge.

Like in a dream, I wanted to move but my feet felt frozen to the floor … I wanted to scream but I was voiceless.

From my paralysis came shame and I closed my eyes as much to my cowardliness as to the violence before me. The second time I looked, Mike’s shoulders were squinched up around his black, wiry hair and his arm was moving as if he were sawing a log. I turned away again but the dull pounding sound was searing. Kit took blow after blow, sitting down, holding onto his seat.

The bus driver, Mr. Barrow, never looked back. He looked up through the rear view mirror and blinked his eyes like Mr. Magoo without his glasses.

“You boys better knock it off back there,” he hollered.

But it was already over. Only the screeching sound of the brakes as the bus came to a slow stop on our street. I stepped past Mr. Barrow, who was leaning over the steering wheel as if he'd been in the fight, and descended. Once on the sidewalk, I pretended to adjust my books but as soon as the bus pulled away, I turned, feeling sick inside.

Kit’s face was covered in blood and his shirt ripped open. As I approached, he put his hand in the air like a traffic cop. Then he started toward the house as if in deep thought, rather than pain.

“What happened, Kit?” I asked him. “Why didn’t you just give him your seat!?”

With the same steady voice I’d heard on the bus, he said something that I wouldn’t fully appreciate until that day in the hospital. “I’d rather take a bloody nose than give up my seat,” Kit said. “It was my seat.”

As it turned out, to my great relief, my father returned to the hospital and seconded my call with Dr. Ritter.

But I realized that whether they’re in white coats, your school or family, people wanting their way are going to push. Kit’s voice whispered to me then as it sometimes does today, serving to remind me that one’s seat doesn’t have to be fought for or explained, but rather sat in and sometimes just held onto.