The six billion dollar question

Obama directs NASA to set new boundaries: Can major space change be embraced?

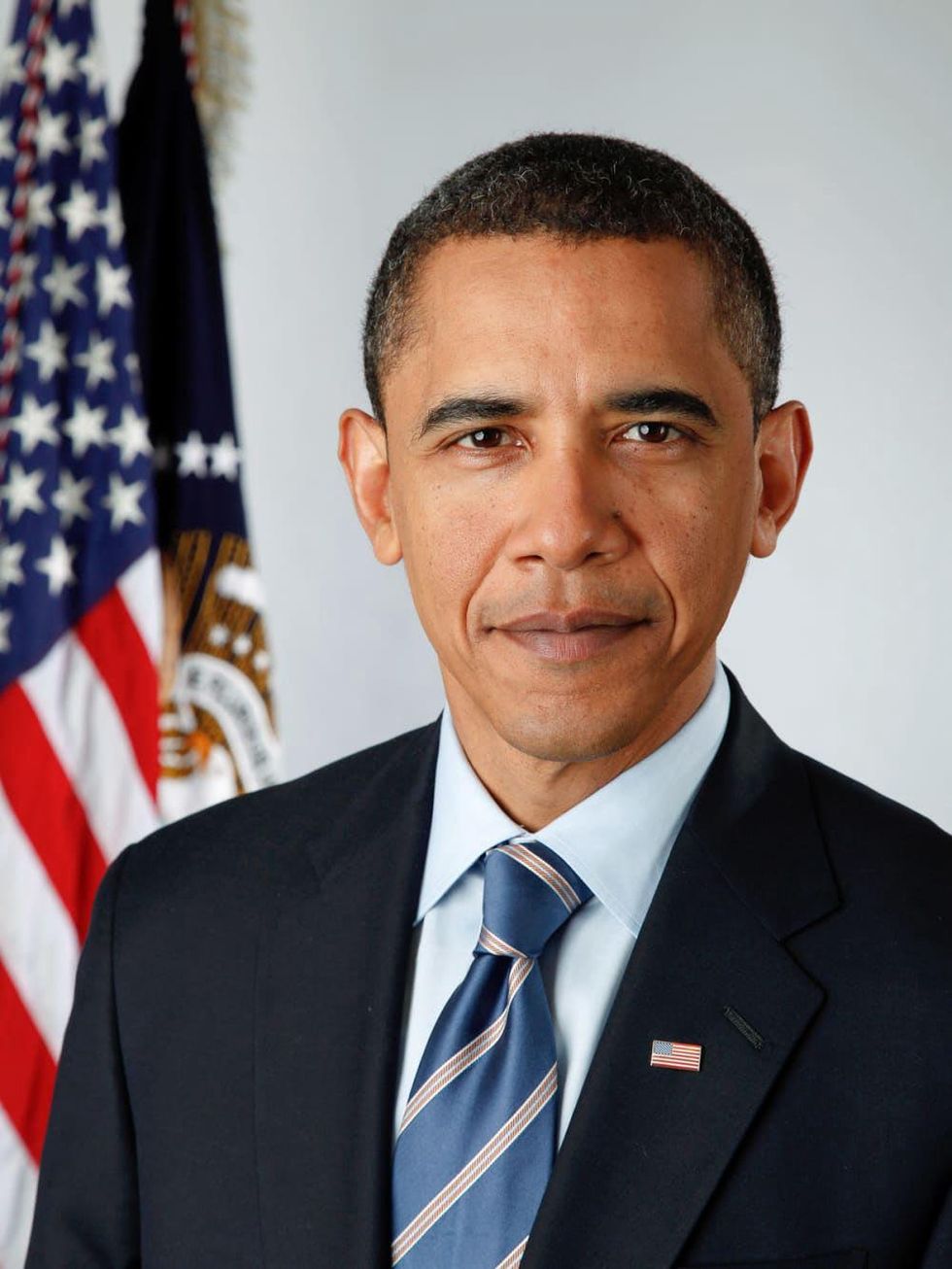

President Obama thrust NASA on a new trajectory this afternoon, one that has thrown the Johnson Space Center and the agency's other human space flight installations in Alabama and Florida into uncharted territory.

Mars is the new destination for American explorers, but at a date uncertain, rather than a return to the moon, as directed by former President Bush in 2004.

During remarks at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, Obama provided his roadmap, one that offers the nation's commercial space industry an opportunity to take over the commercial taxi role filled by the shuttle, which is scheduled for retirement late this year. NASA will extend space station operations from 2016 until at least 2020, a move long supported by the agency's Russian, European, Canadian and Japanese partners.

Johnson will be among the NASA centers assisting in the development of safe and reliable commercial crew taxi services. Other installations, with Johnson participating, will collaborate on the design of a new heavy lift rocket and the other technologies that could start future explorers on journeys to new deep space destinations, including near Earth asteroids, the moons of Mars, and Mars — sometime after the mid-2030s.

Many of NASA's founding fathers, including Apollo 11's Neil Armstrong, are troubled by the vagueness of Obama's plans. They are concerned Obama's strategy lacks the specific destinations and timelines that drove the Apollo program to the moon.

Others view the new strategy as unprecedented in NASA's 52-year history. Yet they believe it holds the promise of snapping the space agency out of costly series of false starts. The syndrome dates back to 1989, when former President George H. W. Bush committed NASA to a return to the moon and a mission to Mars by the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11's triumphant 1969 moon landing. Congress quickly balked.

NASA's Johnson Space Center stands to lose thousands of jobs in the difficult transition if the new program and the supporting aerospace contracts to carry it out do not arrive soon enough. Under the old plan, 2,000 to 3,000 shuttle workers in the Clear Lake area were to transition into Constellation. With Constellation's cancellation, we can double the number of skilled engineers and technical personnel whose jobs in both programs are now in jeopardy.

The space agency has faced an historical Catch-22. It's not had adequate funding to both operate the shuttle, at about $3 billion annually, and develop a successor at the same time. Constellation's goal of reaching the moon with a new generation of explorers by 2020 was simply unachievable under the funding profile of the previous administration.

Fundamentally, that is what Obama is attempting to turn around, with the additional $6 billion he has pledged to NASA over the next five years. "We want major breakthroughs, a transformative agenda for NASA," Obama said. "I'm 100 percent committed to the mission of NASA and its future."

NASA has faced momentous change and emerged with new vigor in the past. As the Cold War ended in 1991, the space stalwarts in Russia reached out to the United States to cooperate. The Clinton Administration responded and directed NASA to turn on a dime to merge the human space flight operations of the two former adversaries. That bond now forms the impressive underpinning of the International Space Station. Russia's cooperation was an essential part of NASA's recovery from the 2003 shuttle Columbia tragedy.

The question now is whether NASA can embrace major change once again. The privilege of leading a multi-national journey to new worlds, a responsibility as inspirational as it is challenging, will depend on it.

Mark Carreau reported on the U. S. space program for the Houston Chronicle for two decades. He's currently a freelance writer/researcher and a contributor to Aviation Week & Space Technology. He can be reached at mark.carreau@gmail.com

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook