CultureMap Video Exclusive

Autistic artist Grant Manier is a rising star: "Coolages" king racks up awards and changes thinking

"That's your first piece?" I question, not doing a very good job of hiding my skepticism.

"That's where it all started," he replies smiling.

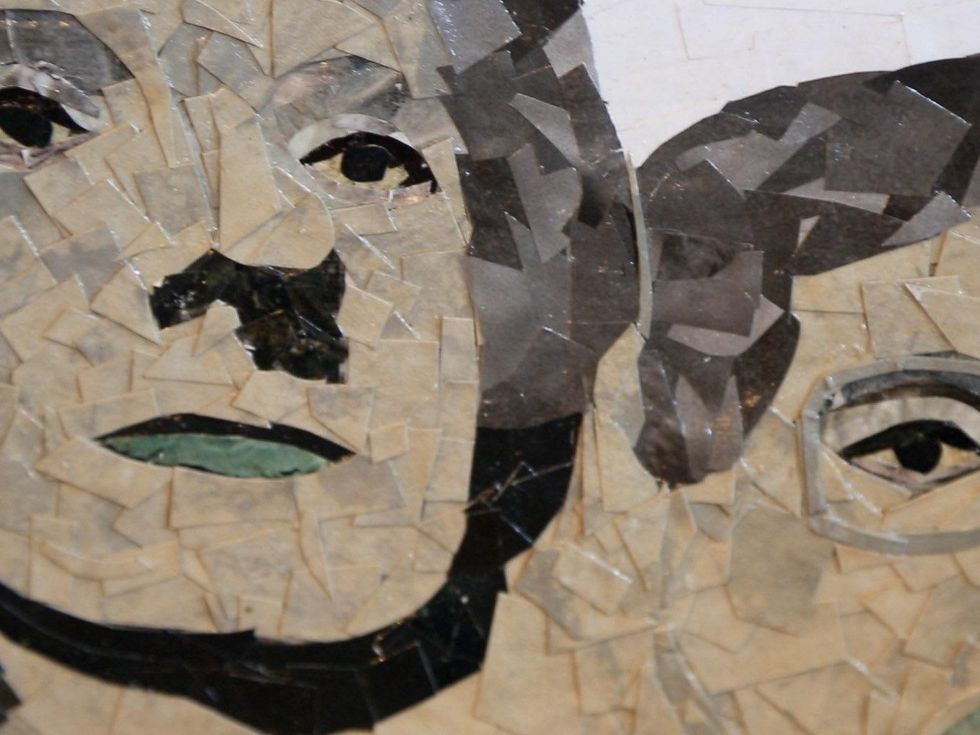

Grant Manier, 17, points to an intricate, vibrant, framed art piece hanging above a console table in his one-story, quaint bungalow in Spring. Grant's Sun God is a trompe-l'œil that first appears to be a painting. It isn't.

More than 3,500 pieces of re-purposed calendars, magazines, gold paper and paint mesh into a collage. A new age, humanized copper-colored sun with blue, violet, red and yellow flames that wave outside of a gold aura is centered amid an undulating lavender backdrop dotted with copper brushstrokes. I can't help hone in on how this complex image emerged from obsolete paper products.

"Really? Your first?" I insist.

Grant just smiles with confidence. He's aware of his gift.

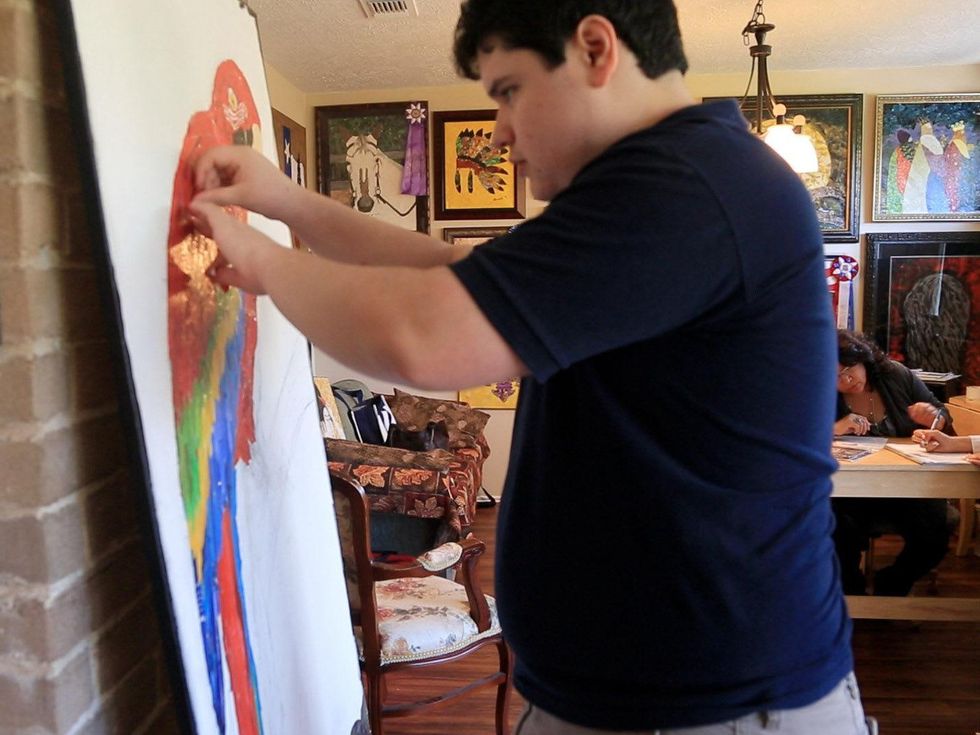

The living room, dining room, kitchen and study are awash with his creations, many of which are crowned with award ribbons from art festivals and competitions. Raw materials are scattered in different places. Canvasses of works in progress evince that Grant is hard pressed for time. As one of the first group of artists accepted in the Rising Talent category of the Bayou City Art Festival, a new initiative aimed at nurturing young, exceptional talent, Grant is on a mission to crank out new collages for the three-day event, set for later this month.

"I can do it," he says, and quickly returns to the task at hand. "It feels incredible to be an artist. I am honored to call myself an artist — and I'm only 17."

"It feels incredible to be an artist. I am honored to call myself an artist — and I'm only 17."

It's easy to connect with Grant's amicable spirit and quirky sense of humor. He's an open book when it comes to his inspiration, his process and technique, but there's something about his personality that isn't readily discerned from spending a morning with him.

It was when Grant was 5 years old that his mother, Julie Manier, discovered he had Asperger's syndrome, a form of high functioning Autism. The condition is typified by difficulties in social situations and repetitive behavioral patterns.

Prior to the diagnosis, the single mother of two boys couldn't make sense of her younger son's behavior. Grant showed signs of extreme anxiety, he frightened easily, lined up his toys and had difficulties associating with his peers. Otherwise a bright kid who excelled in his academic endeavors, Grant found comfort in repetitive activities, one which later would grow meaningfully as his life's métier — and his mother's purpose.

He would tear paper. Lots and lots of paper.

As it's common for people with Asberger's, these types of responses tend to come and go. Grant's ease with scholastic material left much of his day free for leisure and recreation. When he was 14 years old, to curve the time Grant spent watching television, Julie thought of art as a possible solution.

Painting didn't appeal to Grant. But assembling collages did.

"I actually call them coolages," he says. "And there's a funny story about that."

A Prolific Artist

"What I'm trying to say here is: It's not what we can't do, it's what we can do. Or in this case: It's not what I can't do, it's what I can do."

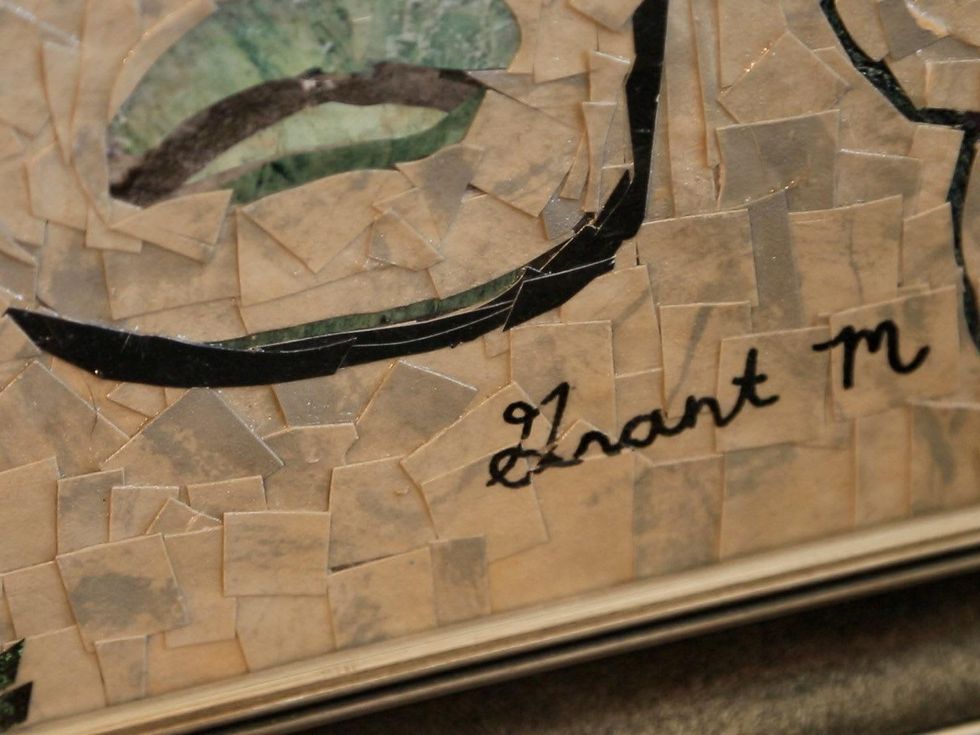

Grant's My Beloved Mt. Rushmore is one of his favorite works. More than 4,500 pieces of recycled poster board, wallpaper, magazines, books, calendars and school folders form the four former presidents' heads, perched atop greenery set apart by a slice of the American flag. His term, coolage, pays homage to former President Calvin Coolidge, who negotiated the South Dakota carving project.

"And, don't they look cool?" Grant says referring to his style. "They all have cool colors, cool shades and cool textures."

Grant is a student at Focus Academy, a center that addresses the educational needs those with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, Asperger's and Tourette's. He attends classes two days per week during which he practices fine tuning his social skills. The rest of the instructional curriculum is completed online, leaving plenty of time to devote to his art, as some of his creations, described as Eco-Impressionism, take more than a month to complete.

"Grant not only came into this world to teach me about Autism," Julie says. "He came into this world to teach me patience."

His assemblage of accolades speaks to his commitment, including a Best of Show in 2011 in an art festival at Rancho Del Lago in McDade, the 2011 and 2012 Austin Rodeo Eco-Art Grand Champion award, and the 2011 Disabilities Youth Advocate of the Year and 2012 Houston Mayor's Student Volunteer of the Year award from Mayor Annise Parker.

A collaboration with Houston Texans linebacker Connor Barwin at this year's Museum of Cultural Arts, Houston gala sold for $4,000 to collectors Susan and Bill Ellis. Some of his original art has been valued at more than $6,000.

Part of Grant's business strategy is giving back to the community. He's raised more than $30,000 through art donations and public speaking engagements, and he plans to employ adults with disabilities to help him develop and grow his vocation.

"People with Autism, my art looks at the brighter side of things," Grant explains. "What I'm trying to say here is: It's not what we can't do, it's what we can do. Or in this case: It's not what I can't do, it's what I can do.

"See?"

I do. I do indeed see. I think everyone can see.

___

Watch the video above for a profile of Grant Manier, filmed and produced by CultureMap's Joel Luks.

As one of the first group of artists accepted in the Rising Talent category of the Bayou City Art Festival, a new initiative aimed at nurturing young, exceptional talent, Grant Manier is busy cranking out art for the three-day event.

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook

The building at 4911 will be torn down for the new greenspace. Holland Lodge No. 1, A.F. & A.M./Facebook