Rothko Masterpieces

Mark Rothko: A Retrospective allows Houston to rediscover the master artist we thought we knew

The Rothko Chapel has been such an integral part of the Houston artistic, architectural and spiritual landscape for so long, we perhaps tend to think of the Russian (now Latvia) born, later New Yorker Mark Rothko as an artist who belongs to us.

So for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston to be one of the organizers and only U.S institution exhibiting Mark Rothko: A Retrospective, it seems just our right.

Though we might feel as if The Rothko Chapel has always been here and always will be, many native Houstonians, including MFAH director Gary Tinterow, who was in high school at the time, can remember the “high drama” involved in the design and building of the chapel. “I was convinced that something terribly important had occurred in my city and that we had this monument to art here,” Tinterow said during a recent preview of this new monumental retrospective.

Mark Rothko: A Retrospective is the first major review of the art of Rothko this century, with the majority of the paintings coming from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C, along with select works from the Menil Collection and the MFAH. Such a exhibition, of more than 60 paintings, that spans Rothko’s career will give Houstonians a chance to go deeper into his legacy and make new discoveries of an artist we might think we already know so well.

An Artist Searching for His Language

The exhibition runs mostly linearly through Rothko’s painting life. Moving through the galleries in the Beck Building, visitors will see the evolution of this great master of Abstract Expressionist. The first gallery in particular is a bit of a wonder as we meet a young Rothko toying with figure studies, still-life compositions and Surrealism. Here is a Rothko his many 21st century admirers probably never knew existed.

Alison de Lima Greene, curator of contemporary art and special projects, who coordinated the Houston presentation and led the preview walk-through of the exhibition, pointed out that if we turn certain of his paintings 90 degrees in our imaginations, like the subway scene in Underground Fantasy, we might catch a glimpse of the tiered color compositions of Rothko’s future.

But should we see these works as predictors of what is to come in later decades for Rothko — just a few steps into the next gallery for us — or see these early works as a man testing for the perfect “language” as Greene described, for his art?

In the middle galleries, we encounter the Rothko we know, with his Color Field paintings and their rectangles of such depth of color it’s difficult not to want to dive into them. Early in these middle galleries, we can also see Rothko still experimenting, especially when juxtaposing paintings of similar color that are seldom seen together because one belongs to the Menil and another the National Gallery.

Greene also disclosed a secret in the creation of those vibrant, changing colors was not necessarily in the paint but the use of turpentine.

“We don’t have clear record of the paints he used, but he kept vast inventories of the turpentines, the thinners that allowed the paint to become almost like a water color wash and that allowed him to layer color,” Greene described, relaying a fact she had recently learned from Mark Rothko’s son Christopher, who was in Houston for the exhibition’s opening.

For those who have seen the dramatic, but probably not that accurate play, Red, which was performed at the Alley Theatre in 2012, the exhibition also includes full-sized studies for unrealized mural commission for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building.

Dark and Life

The final gallery highlights the work Rothko did towards the end of his life. After he suffered a heart attack in 1968, he received medical advice forcing him to give up oil paint and his beloved turpentine because of the fumes. Yet his taking up acrylic painting allowed him to move into new directions. While some critics argue the somber and dark palates of his later years are a manifestation of his struggle with depression and perhaps even a foretelling of his suicide in 1970, Greene believes there are signs of new beginnings in his last paintings and “so much promise and so much excitement.”

The exhibition ends with the unfinished, glorious red Untitled from 1970, a work that feels blazing with life.

Early during the walk-through of the exhibition, Greene made a point about Rothko’s refusal to decipher his work for others.

A Private Conversation

“Rothko is famous after around 1950 for almost becoming totally silent about his own work. He gave very few interviews after that period, believing that the paintings spoke for themselves,” she explained.

The MFAH provides informative wall texts throughout the galleries as well as an audio tour filled with notable Houstonians musing on their own thoughts and perceptions of the paintings, but above all, the organization of the exhibition and the nature of the paintings themselves encourage a private dialogue between viewer, artist and his creations.

While sitting at the center of the Rothko Chapel might allow us quiet contemplation into our own spiritual interiors or to reach outward for some sense of universal divinity, walking through Mark Rothko: A Retrospective gives us an intimate encounter with the humanity of the man himself and a deeper understanding of the breadth and beauty of his art.

Mark Rothko: A Retrospective runs until January 24, 2016. The exhibition is ticketed.

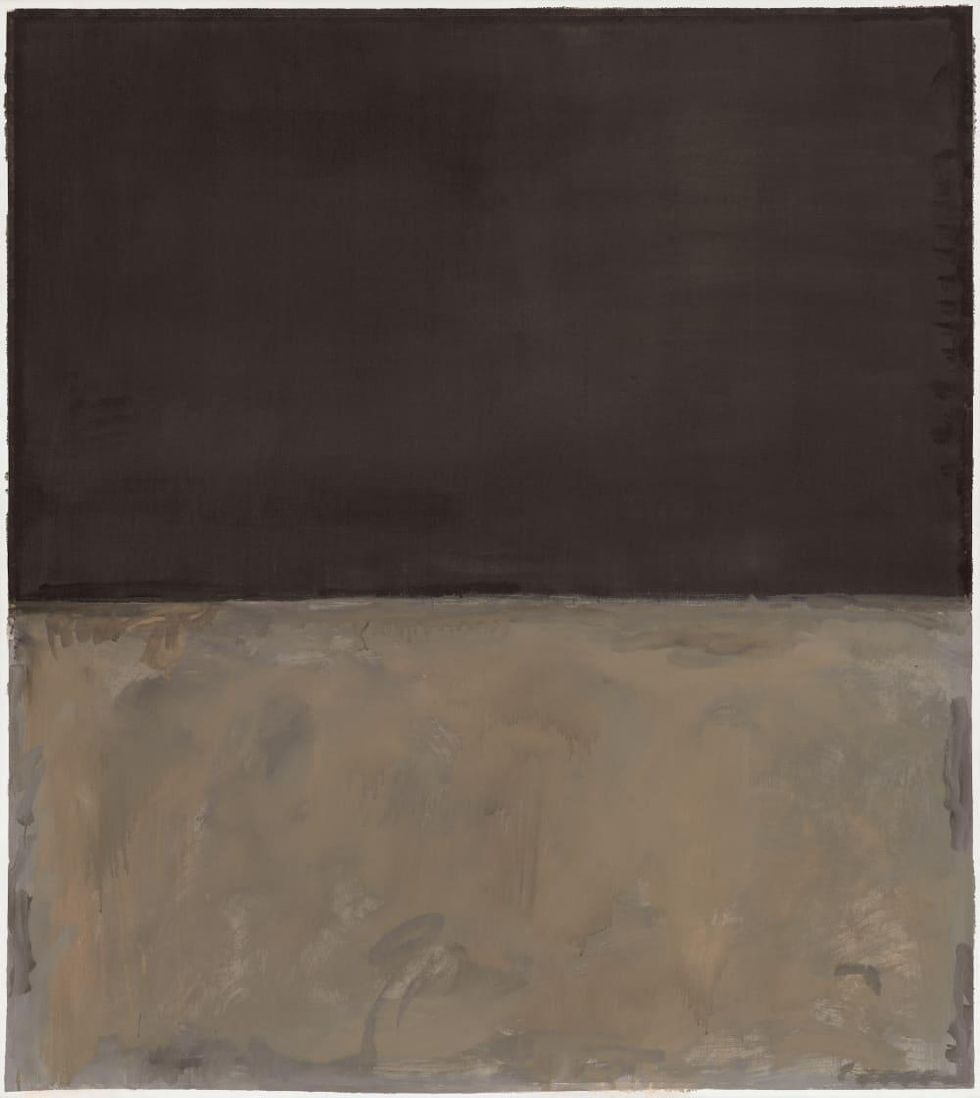

2 | P a g eMark Rothko, Untitled, 1953, mixed media on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc. © 1998 by Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.