From the Budapest Opera to Auschwitz

Tales from the trenches: Holocaust survivor curates Houston concert to honor the living & the lost

"Sing, Jew! Sing!"

The horrors of life in four concentration camps during World War II are permanently imprinted in the life's purpose of Al Marks, then a teenager. Amid the memories that haunt this charismatic, witty and warm-hearted musician is the sweet voice of another Jewish prisoner whose friendship brightened the savagery brought on by misplaced hatred and prejudice that transformed his native Rákoscsaba, Hungary — today a suburb of Budapest — into an internment center from where hundreds of Jews were locked in cattle carts and deported to Birkenau and Auschwitz.

It was at gun point that a Schutzstaffel officer commanded the late Ferenc Fellner, a practicing physician and well-known Hungarian opera singer who graduated from the Liszt Academy, to offer arias from noted operatic repertoire. The juxtaposition of the inhumane order atop the allure of his voice has stayed with Marks as a testament that beauty can be found through challenging trials.

Both men survived their captors; Marks, born as Albert Markovits, an only child, found safe passage, first to New York and then to Houston, and Fellner returned to Budapest.

Marks has curated a concert that honors Fellner at the Holocaust Museum Houston. "From the Budapest Opera House to the Gates of Auschwitz," set for 6:30 p.m. Sunday, programs uplifting and beloved arias from opera and operetta, a collection of tunes that echoes with Fellner's repertoire and spirit. Hungarian soprano Dalma Boronkai Rodriguez and Mexican tenor Antonio Rodriguez, husband and wife, both Shepherd School of Music graduates, will sing selections from Puccini's La bohème and Gianni Schicchi, Verdi's Rigoletto and La traviata, Franz Lehár's The Merry Widow and arias by Johann Strauss and Emery Kálmán.

Fellner, Marks says, may have saved his life.

"In every camp, there were elites," Marks recounts. "These elites worked just as hard and got into just as much trouble as anyone, but because of their intellect — some were politicians, some were doctors — their status was a little bit higher than the average prisoners. Fellner was one of them — and he spoke fluent German."

"Everyone looked like walking skeletons; not even human beings. I assume the SS didn't bother to do any more killings because they thought most were just a few days from death — from hunger."

The day before the Ebensee concentration camp was liberated by the U.S. 80th Infantry Division on May 6, 1945, German officers had plans to execute the 16,000 captives still alive despite the center having one of the highest prisoner death rates. But they didn't. Instead, they suggested survivors find shelter in some of the underground tunnels, where V-2 rockets were previously hidden, as an attempt to "endure" the American "attack." What the prisoners didn't know is that a concealed 2.5-ton truck filled with explosives would blow up and claim their existence if opposing forces were to strike.

"Everyone looked like walking skeletons; not even human beings," Marks says. "I assume the SS didn't bother to do any more killings because they thought most were just a few days from death — from hunger."

Someone had to make a decision: Whether to access the tunnels or remain exposed to the elements. Fellner was one of the men who persuaded the group not to follow Nazi instructions. Instead, he insisted that even if there were shootings, someone was destined to persevere. And that's all they needed: One survivor to be a witness to this story.

A new world

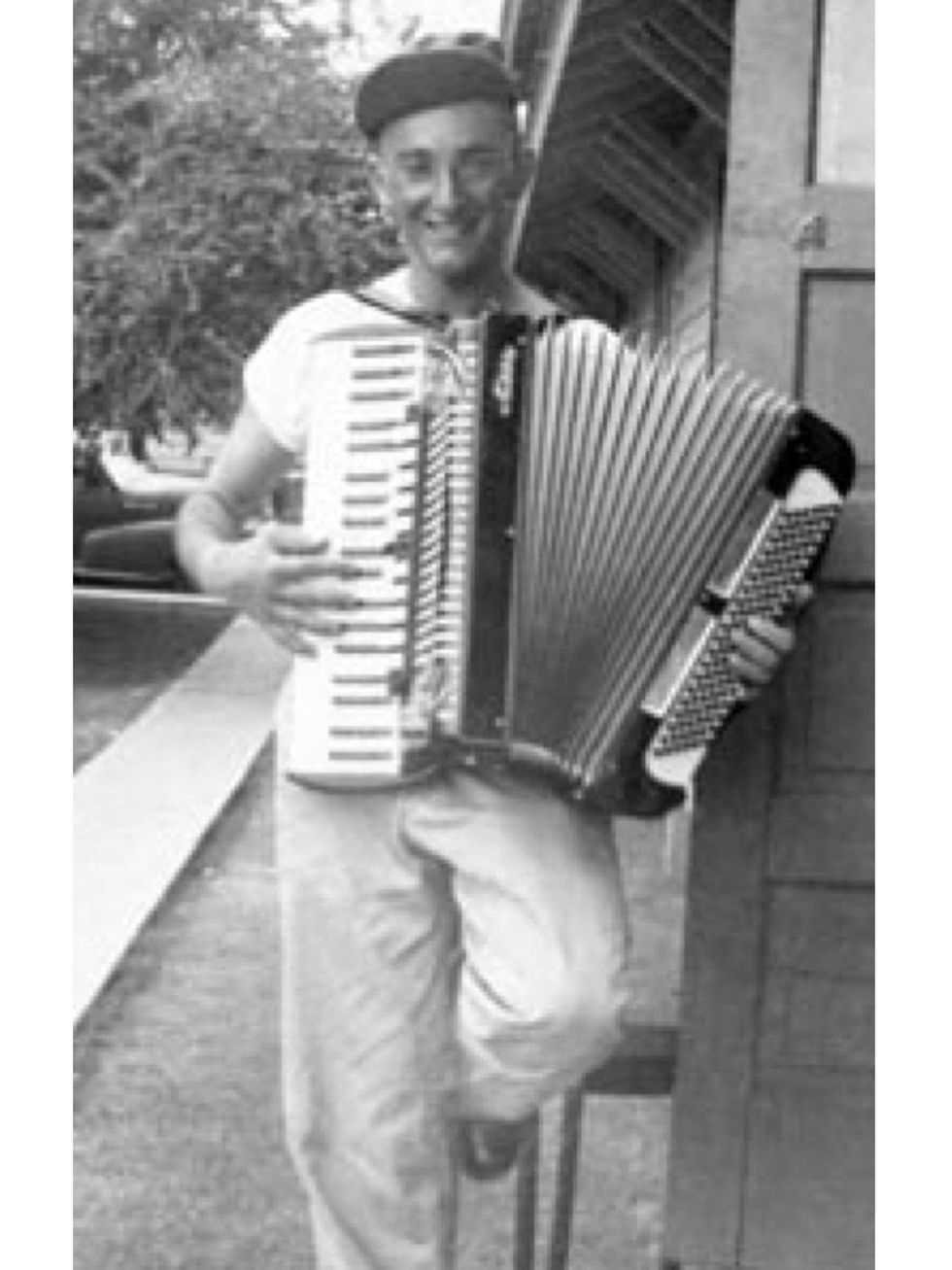

With one dollar in his pocket and an old, beat-up accordion, Marks arrived in New York, welcomed by 22 inches of snow, when he was 16 years old in 1947. A sponsoring social worker picked him up at a shipping dock, and made arrangements for him to stay in a large home with other displaced Europeans. He resided there for five weeks, but the Big Apple didn't feel quite right.

"The social worker named three places where I go could, and I didn't know any of them," Marks recalls. "I left it up to her, and that's when she said, 'I'm going to send you to the best place for you — Houston, Texas.' I had never heard of Houston up until then."

Marks remembers his first days in Houston clearly. Sunshine. Residents wore short sleeves. He was given $60 dollars a month for school and room and board. Although his allowance didn't go very far, it was enough for him to attend school, get a music education that focused on music history and theater, find work and restart his life's journey. He often thought about his loving parents — his father, Alex, a red cap at a train station in East Budapest and his mother, Margaret Ungar, a homemaker — both of whom perished, victims of Dr. Josef Rudolf Mengele's medical experiments on humans.

In 1952, Marks served in the U.S Army in artillery, and serendipitously he was sent to support efforts in Germany.

"She was a pretty girl in school. It's not easy being married to a musician, as we traveled a lot from Galveston to Europe. We've been married now for 58 years."

"I was a field soldier, and my job was in computers," Marks says. "But now I am the stupidest man to be on a computer. I am lucky if I can turn one on nowadays. For the army, computers meant being proficient at trigonometry — very different from what computers mean today — so I learned computation for that."

Back in the Bayou City, Marks organized an 11-piece band, one that became very popular for weddings, Bar Mitzvahs and special events. In poring over the guest list for Sunday's concert, he reminisces about a marriage ceremony at which he performed 60 years ago. That couple is attending.

"She was a pretty girl in school," Marks quips about meeting his wife, Sarah. "It's not easy being married to a musician, as we traveled a lot from Galveston to Europe. We've been married now for 58 years."

Music connections

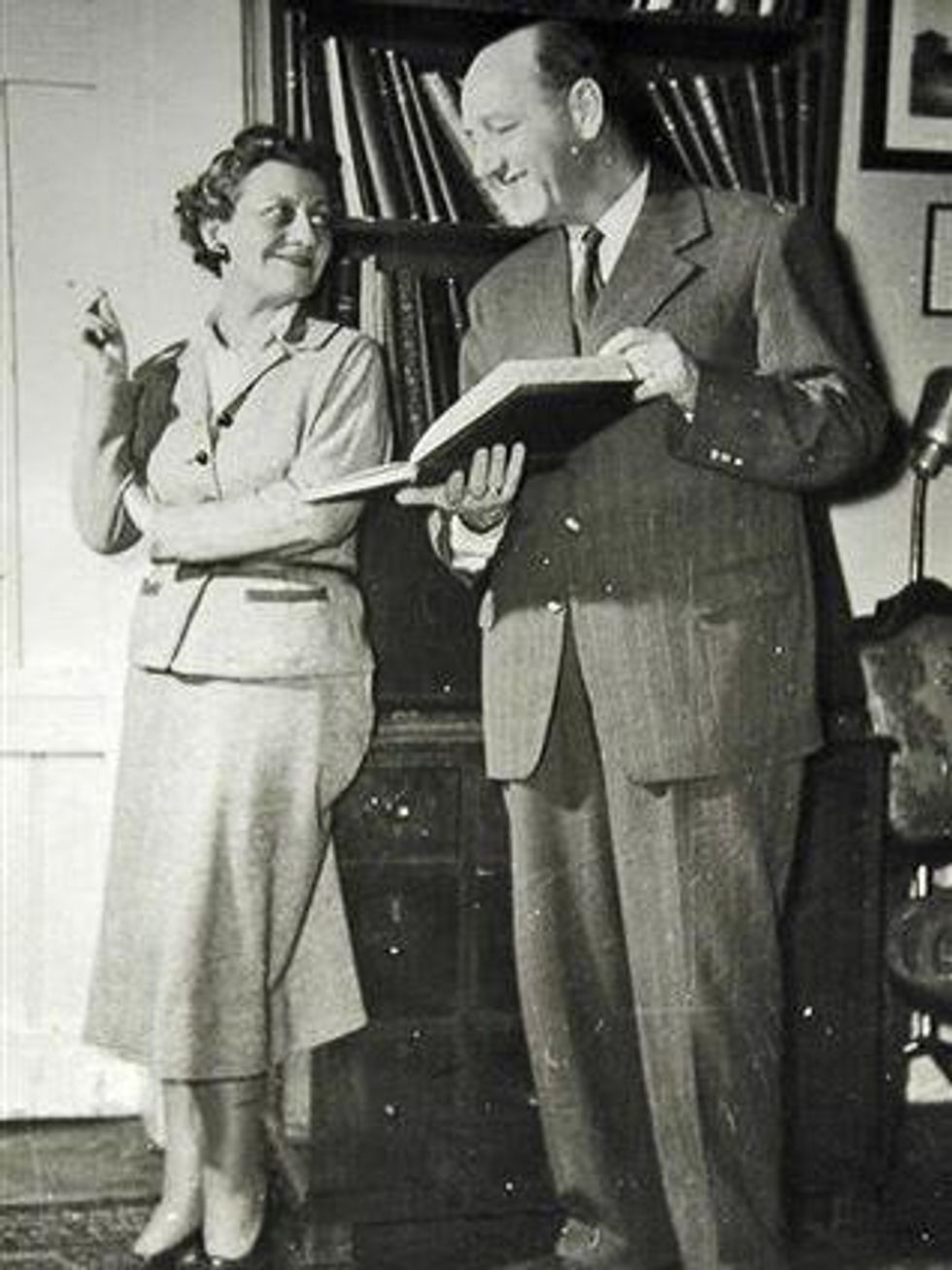

It was during happier times when Marks met Hungarian bass-baritone József Gregor, another honoree of the Holocaust Museum Houston Sunday performance.

"Gregor was a dear friend," Marks says. "When we first spoke in Houston, we became instant friends when we realized we both came from a neighboring suburb in Hungary. When he would visit Houston, my phone would ring — didn't matter what time — with a request to do coffee, even before 7 in the morning. He would say, 'I don't care where you are, I don't care what you are doing — I need to see you.' "

Gregor, like Fernell also a student of the Liszt Academy in Budapest, though he never graduated, would find himself in Houston often to perform with the Houston Grand Opera. He was cast as Rossini's Don Basilio from The Barber of Seville in Cecilia Bartoli's American stage debut in 1993. The roles of Sarastro, Falstaff, Boris Godunov and Mephistopheles were associated with his virile vocals.

Yet notwithstanding his international reputation and busy professional schedule, Gregor made a point of showing Marks what was important to him. During one of Marks' trips to Budapest, Gregor picked up Marks en route to one of his concerts.

"I didn't know where we were going," Marks says. "A person like Gregor could be singing at the presidential palace. But instead, we approached one of the worst areas of Budapest — a real ghetto. Gregor was singing in an old age home for Jewish people. He sang with the same beauty he would have on any prestigious concert stage."

Gregor, a devout Christian, passed in Budapest in 2006 from gastric cancer.

"We aren't going to change the minds' of older people, the ones who have their minds set about something. But children? I can do that."

Marks' Houston

Marks, 81, doesn't perform much anymore. He prefers to spend his time giving lectures and talking about his experience. He says that for history not to repeat itself, he has to tell his story to young people.

"We aren't going to change the minds' of older people, the ones who have their minds set about something," he laments. "We are not going to change them. But children? I can do that, and always begin by telling them that I am here to learn as much from them as they are from me. It's a two way proposition."

Although Sunday's concert isn't aimed at children, per say, it's in alliance with Marks' hope that these personal accounts don't recede in history as anecdotes destined to repeat themselves, but rather as a tribute to a world of hostility that ceased to exist all together.

That he's doing it through music — his life's metiér — well, that's just the cherry on top.

___

Holocaust Museum Houston presents "From the Budapest Opera House to the Gates of Auschwitz" on Sunday, 6:30 p.m. Tickets are $30 for non-members, $20 for Holocaust Museum Houston members, and can be purchased online or by calling 942-8000.