50 Years Later

The day JFK died: TV anchor recalls exclusive interview with assassin's mother

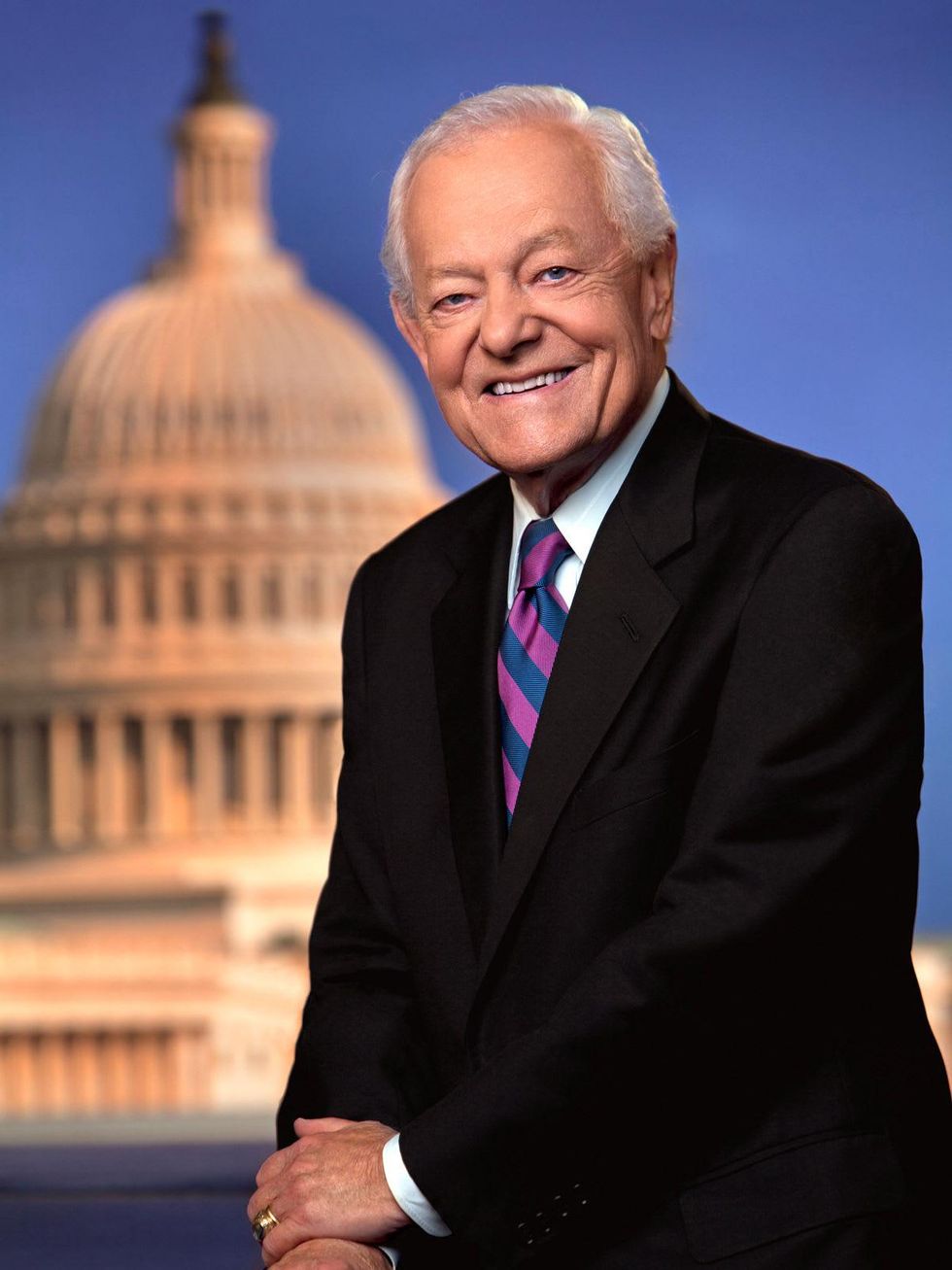

Last weekend, Bob Schieffer returned to the scene of the crime.

The veteran CBS newsman and longtime Face the Nation host was in Dallas – specifically, in the former Texas Schoolbook Depository, now the site of the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza – to conduct interviews and tape commentaries for his Sunday morning program, as part of his network’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

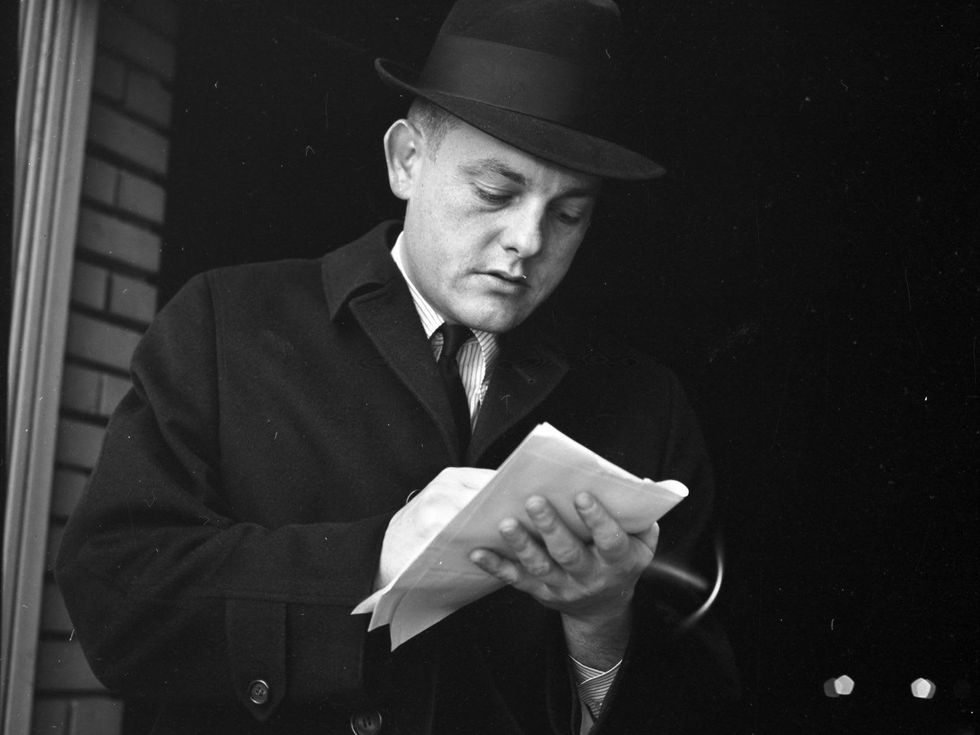

Back in 1963, on the day of that dreadful crime, the Austin-born Schieffer – then a hustling young reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram – was working in his newspaper’s city room, ready to take calls from reporters filing stories from Parkland Hospital, Dealey Plaza, Dallas Police Headquarters and other locations, when he grabbed a ringing phone. “In all my years as a reporter,” he would later recount in his 2003 memoir This Just In: What I Couldn’t Tell You on TV, “I would never again take a call like that one.”

What happened?

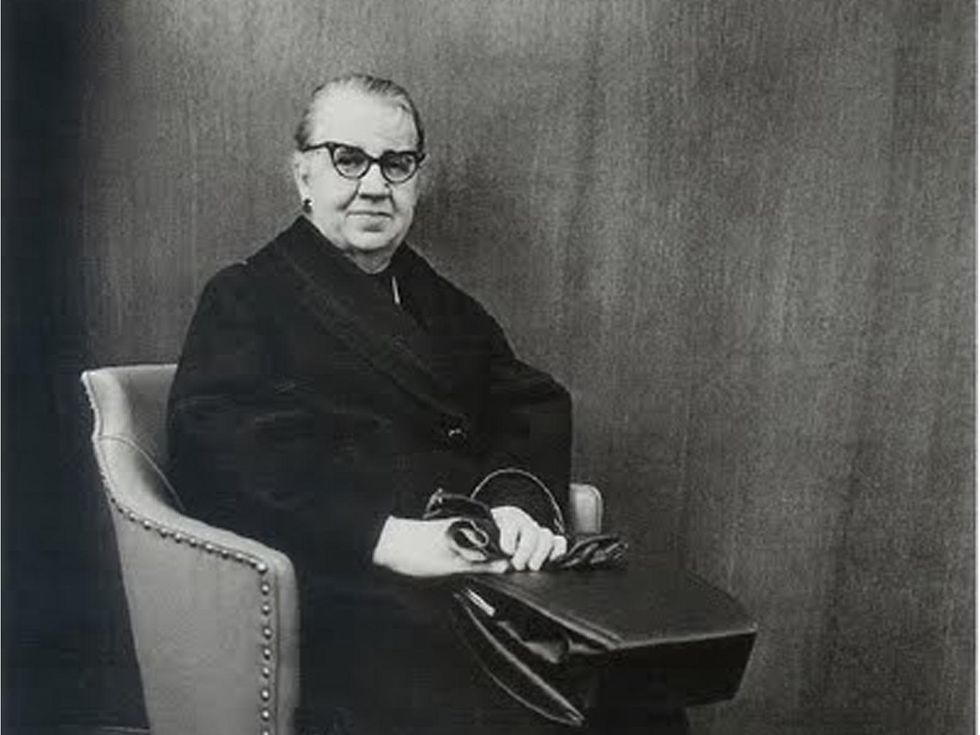

“A woman’s voice asked if we could spare anyone to give her a ride to Dallas.

“’Lady,’ I said, ‘this is not a taxi, and besides, the president has been shot.’

“’I know,’ she said. ‘They think my son is the one who shot him.’

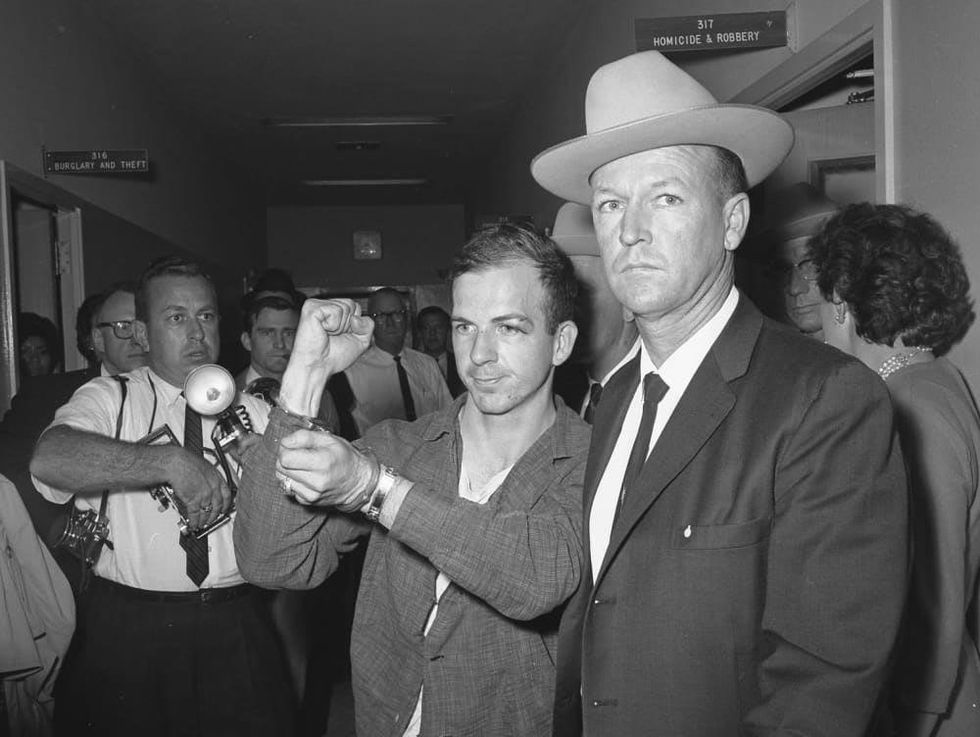

“It was the mother of Lee Harvey Oswald, and she had heard on the radio of her son’s arrest.

“’Where do you live?’ I blurted out. ‘I’ll be right over to get you.’”

He has never forgotten the terrible events that unfolded five decades ago, during what he calls “the weekend America lost its innocence.”

And that is how 26-year-old Bob Schieffer landed an exclusive, career-boosting interview, conducted primarily during the hour-long drive from Fort Worth to Dallas, with Marguerite Oswald.

Schieffer went on to become the first reporter from a Texas newspaper to report from Vietnam, and then reinvented himself as a broadcast journalist – first at WBAP-TV in Dallas/Fort Worth and later, from 1969 onward, as a member of the CBS news team. During his lengthy tenure with the network, he has covered all the major Washington beats – The White House, The Pentagon, Capitol Hill and the State Department – and logged thousands of hours of airtime covering everything from political conventions to country music icons. He served as anchor of the Saturday edition of the CBS Evening News for 20 years, and has hosted Face the Nation since 1991.

And yet, despite his many accomplishments elsewhere, Schieffer has always remained passionately and indissolubly attached to Texas. Just as important, he has never forgotten the terrible events that unfolded five decades ago, during what he calls “the weekend America lost its innocence.”

During production breaks at the Sixth Floor Museum, Schieffer graciously shared some of his memories about that unforgettable weekend.

CultureMap: Have you ever thought about how differently your career might have turned out if you hadn’t answered the phone at that particular moment on Nov. 22, 1963?

Bob Schieffer: [Laughs] You know, it was just one of those things. Total happenstance. I think that most stories that I’ve gotten over the years, I’ve gotten because I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. I think that’s how a lot of reporters get their stories. I think that’s why one guy gets the Pulitzer and another guy doesn’t. You just happen to be where the news is happening.

CM: I guess what might seem so odd to anyone who wasn’t alive back then is, Marguerite Oswald’s first impulse was to call a newspaper to get a ride to Dallas.

Schieffer: Well, when her son had defected to the Soviet Union, we had done a story about it. And she had dealt with reporters along the way on that. And she was such an outsider. You have to remember: These people were not from Texas, they were not of Texas. They were itinerants – they had lived all over. They’d be one place for a while, and then she’d move them to another place. At one point, she put Lee Harvey Oswald and his brother in an orphans’ home, and told them they were a burden to her. She’d been through multiple marriages. And I don’t think she knew anybody else to call. She’d worked as a practical nurse, and as a babysitter, and as kind of an au pair for various people. And I think because somebody at the Star-Telegram had dealt with her, that’s why she called.

Actually, I didn’t find out until this year that earlier that day, she called the home of Jack Douglas, who was one of the editors of the Star-Telegram. But he and his wife were not there – they had gone down to see the President. And their 11-year-old son had been sent home from school after they had announced that the President had been shot. And when she called this house, this 11-year-old answered the phone. And when she said, “I need to get ahold of your father, I need to talk with him,” he said, “Well, he’s at work. But here’s the telephone number.” And I guess that’s when she called up the Star-Telegram – and I just happened to be the one who picked up the phone.

CM: But, again, the idea that Marguerite Oswald or anyone else would think of seeking help from staffers at a newspaper office at such a moment – that’s probably unfathomable to most folks below a certain age.

Schieffer: Yes, but you know, in those days, newspapers were so much a part of the community. There was no security system there – it was not at all like it is now. People could just walk in off the street. If they didn’t like a story that was in the Star-Telegram, they’d come up and complain to the city editor. There was an old man named Monroe Odum, who was almost blind, and he sold Star-Telegrams out on the street in front of the Worth Hotel, which was right next door to the Star-Telegram. And if he didn’t like the headline on the first edition, he’d come up and complain to the editor. He’d say, “I can’t sell a newspaper like this. Put some news on the front page.”

That’s just kind of how it was – we were so much a part of the community. So while it was odd and unusual that Marguerite Oswald called – it was not that weird that people would call the newspaper.

CM: For nearly two decades after 1963, you couldn’t mention the word Dallas anywhere in America – probably anywhere in the world – without people saying, “Oh, yeah, that’s where Kennedy was killed.” It was as if the entire city had been stained, even damned, by the actions of one man, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Schieffer: Yes. There’s no question about that. And you’re hearing this from a guy who grew up in Fort Worth – and there was never any love lost between the two cities. But Texas and Dallas were seen as places for these right-wing hate groups. The John Birch Society was very big here. But actually, these were just pockets of right-wing hatred. When [President Kennedy] came to Fort Worth, 10,000 people came out at 10 o’clock at night to see him. The next morning, there were 5,000 people in the parking lot outside the Hotel Texas. There was a sold-out luncheon of Fort Worth’s A-list. And they weren’t all Democrats by any stretch. People just couldn’t get enough of him. They loved him. Ruth Carter, who was Amon Carter’s daughter — she and some other people got together this priceless art collection. Van Goghs, Picassos, all of this stuff. And they hung them in the suite where the Kennedys spent the night in the Hotel Texas. They just wanted to do something nice for them. That’s how people felt.

Nellie Connally, John Connally’s wife, said as they rounded the downtown area, “You can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you, Mr. President.” And that was absolutely accurate. And then this happened.

And you know that just minutes before the President was shot, they had that big reception for him at Love Field. They crowds were cheering him on during the motorcade. Nellie Connally, John Connally’s wife, said as they rounded the downtown area, “You can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you, Mr. President.” And that was absolutely accurate. And then this happened.

But [Lee Harvey Oswald] was not of Dallas. He wasn’t from Dallas. He was a loser. A deeply disturbed failure at everything he had done. A week before, his wife had accused him of being impotent. He couldn’t get anything right. And he was about as far from the right-wing as you could get. I mean, he’d tried to kill Edwin Walker earlier that year. He was a Communist, a Communist sympathizer. He was a Castro sympathizer.

And it’s interesting, some of the reporting that has come out about him in the past couple of years. We all knew about him going down to Mexico. But while he was there, he went to the Cuban embassy to try to get a visa to go to Cuba. And they said, “No thank you.” They didn’t want any part of him. They thought he was nuts.

Like I say: This could have happened anywhere, in any city or any state in the country. It had nothing to do with Dallas. This was a deeply disturbed man. And to think that someone like this could have cut down the President…

CM: Which is, really, to my mind, still the scariest aspect of this tragedy. I know there are people – intelligent people -- who believe in conspiracy theories. But I have always felt that Oswald acted alone. If there was any sort of cover-up, I think, it was a cover-up after the fact by people who should have had Oswald on their radar before he could pull the trigger.

Schieffer: Well, the FBI and the CIA both withheld information from the Warren Commission. And we now know that through the reporting in recent years. But, again, it was a CYA deal. They were not part of a conspiracy. They were just afraid they were going to be blamed for not keeping [Oswald] on their radar, as you say.

CM: Would you agree that, for a lot of people, the notion that JFK was killed because of an elaborate conspiracy isn’t nearly as frightening as the likelihood that a single crazed gunman had such an impact on history?

Schieffer: In a funny kind of way, yes. It was hard for them to accept and process that somebody who was a total loser was able to kill the person who held the most powerful office in the land. And I think that’s one reason why we have all of these rumors and all of these tales of conspiracy – it just didn’t fit into people’s plotline that something like this could possibly happen. But I think it probably did.