The Fault Of Our Stars

Houston Ballet reaches for the heavens but falls to earth in star-crossed performance

People look to the stars for cosmic secrets or the key to human nature. Recent downpours make Houstonians look up with worry, not wonder, at the heavens. So a night at Houston Ballet with Jiří Kylián’s "Svadebka," Mark Morris’s "The Letter V," a world premiere choreographed for Houston Ballet, and Stanton Welch’s star-inspired world premiere of “Zodiac,” promised reprieve.

In spite of the clearing skies, it was a night more water-logged than wondrous.

In spite of the clearing skies, it was a night more water-logged than wondrous.

"Zodiac," set to music by Ross Edwards, began inauspiciously with 12 men in Greek war helmets stomping ineffectually on the ground, which is how the performance would also come to a whimpering end. There was neither sufficient unison nor volume to produce much effect.

This was not the only indication that "Zodiac" was born under a bad sign. It was exceedingly literal about its starry subject matter. “Sagittarius,” the archer, made sure to stretch and shoot his bow several times while "Pisces" was accompanied by an irritating cascade of water sounds, as if someone had left a rather loud toilet running backstage.

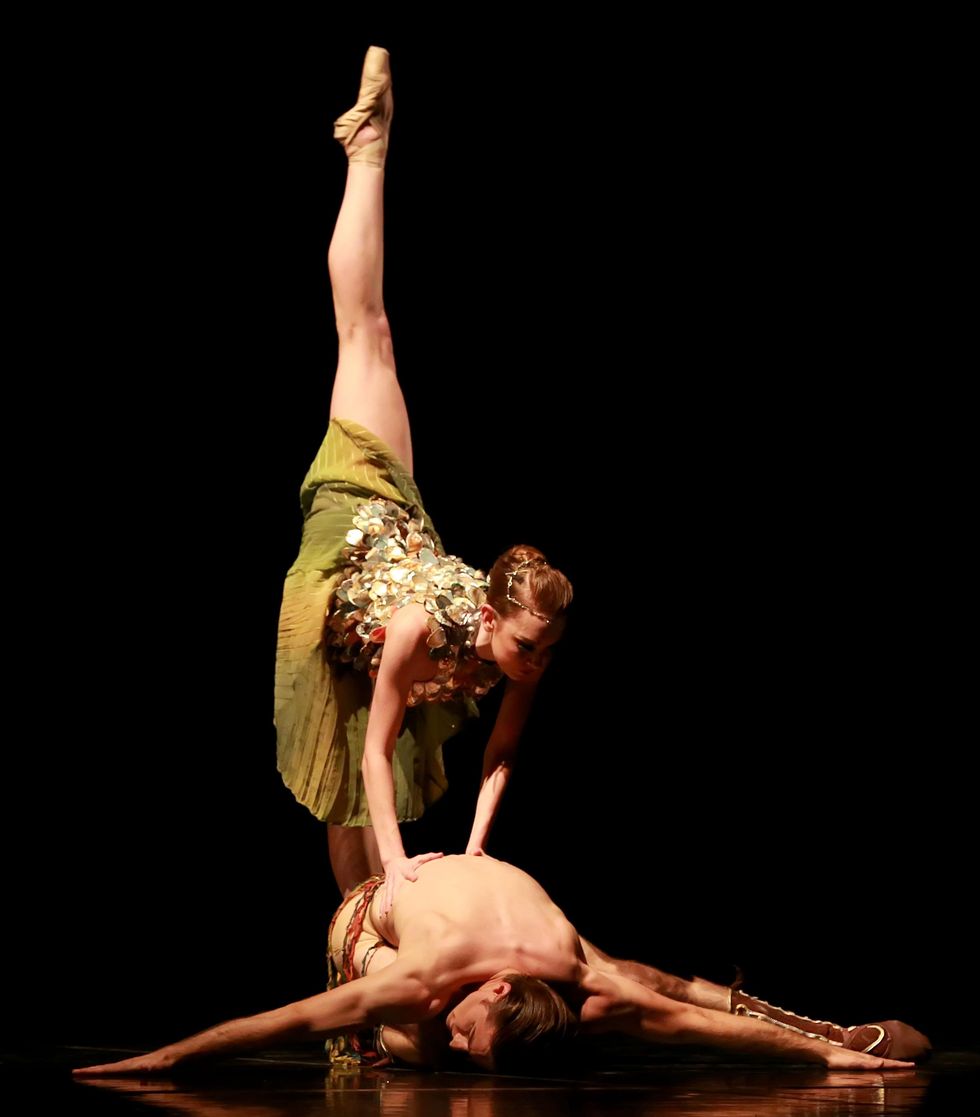

By far the strongest moments came in pas de deux. Simon Ball and Jessica Collado impressed as Capricorn, as did Connor Walsh and Melody Mennite as Scorpio. But the highlight of "Zodiac" was Christopher Coomer and Yuriko Kajiya’s delicate and intimate Cancer, appropriate for a sign associated with great sensitivity and emotion.

That I myself was born under that particular sign bears no influence on this judgment.

The zodiac offers ample excuse to aim high. How sad that the costumes seemed dragged from the bottom of a Bob Mackie reject pile for an endless run of Cher at Caesar’s Palace. Bedazzled loincloths and overwrought drapery still left the dancers overexposed and gaunt in appearance.

The great dance of the stars and the planets has inspired people of all cultures for millennia. "Zodiac" felt like twelve vignettes in search of a purpose, leaving the audience counting down from twelve to one so they could out for intermission after a minimum of polite applause.

Svadebka: Marriage and community

Kylián’s "Svadebka"offers another name for Stravinsky’s iconic ballet "Les Noces" ("The Wedding"), originally choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska in 1923. The genius of Kylián lies in his ability to honor the ghost Nijinska by integrating her iconic gestures — a quirky tilt of the head to the side, for example — with his habitually virtuosic and intelligent athleticism.

"Les Noces" celebrates marriage but it is all about community, which Kylián captures with the perfect symmetry of ritual. The curtain opens on a rustic structure suggested by beams and a suggestively closed door upstage through which the couple will walk at the end. The men and women perform primarily as separate communities, though they often mirror one another.

A night at the ballet when Simon Ball appears in all three works is a good night indeed.

While Jessica Collado and Katharine Precourt perform ably as the bride and her mother, the groom’s party won the night. At one point, Ian Casady, the groom, found himself partnered by matchmaker Connor Walsh. The groom’s father, Simon Ball, later joins arms with them making for an unexpectedly potent and poignant moment.

A night at the ballet when Simon Ball appears in all three works is a good night indeed, I found myself thinking as I marveled at his distinguished and long career, which I began to follow years ago when he danced for Boston Ballet.

The great treat of "Les Noces" lies in the experience of live song. My first "Les Noces" was Michael Clark’s "I do," which I saw in New York accompanied by scintillating voices that still, seven years later, tingle my spine. The Houston Chamber Choir and soloists Nicole Heaston, Carolyn Sproule, Robert McPherson, and Liam Bonner were adequate but not exhilarating. This would be an accurate diagnosis of the company, as well, which usually offers such stirring performances of Kylián.

It was as if someone had inadvertently dimmed the lights and neglected to turn them back up.

The Letter V: Falling stars

Nothing made me more excited for Mark Morris’s "The Letter V" than watching with a friend the recent PBS screening of his 1988 masterpiece "L’Allegro, Il Penseroso, ed Il Moderato," based on the poetry of Milton and set by Handel.

If there were a list of choreographers for whom I would drive through this week’s devastating rains, Morris would make the list. I’m not sure "The Letter V," named for Haydn’s symphony 88, would make a similar list of dances.

The glorious second section features Morris at his best.

"The Letter V" is a deftly and delicately woven marvel that works through accumulation. So often, with Morris, one feels as if the dance in question is just a small part of a much larger pattern. Often his dancers tease the audience, entering only to exit soon after. The gestures are as likely to be classical as cheeky.

The glorious second section features Morris at his best. A couple enters but only one dancer remains. Then the departed dancer enters again with a third dancer, who then leaves only to return moments later. Eventually, five dancers remain on stage, and their occasional unity is most often outshone, to great effect, by their own private moments and movements to Haydn’s score. The third section features the entire cast: eight men and eight women in concentric circles, sometimes spinning separately and sometimes threading complexly through one another.

A particular pleasure of Morris’s choreography is that you can anticipate patterns slowly realized before you. His genius is rooted in progressively revealed architectures whose harmony is well-nigh irresistible.

Just as I was thinking this, a dancer made the first of two falls in the third section. Falls happen, to be sure, but the spell was broken. Once it was broken I couldn’t help thinking that this felt a little too much like "L’Allegro"-lite. And then the spell was broken again with a bizarrely abrupt ending. The music stopped and the curtain descended with a feeling of great incompletion.

Perhaps sequence contributed to this sense of diminishment. The brevity and effervescence of Morris might have made for a stirring opening. Welch’s premiere might have benefited from a less portentous middle slot. And perhaps the dancers might have warmed up to the heft and resonance of Kylián’s substantial "Svadebka" if it had closed the program.

It’s easy to second guess choices on a lackluster night, but who wouldn’t rather see stars rising rather than sinking into retrograde?

--------------------------

Performances of Morris, Welch & Kylián continue through June 7. For more information, visit the Houston Ballet website.