Get Artsy

Murder mystery hidden within a new Houston art exhibit: When math, spies and assassination collide

Hovering at the core of El Paso-born artist Michael Petry’s glass installation AT the Core of the Algorithm is a historical mystery: How did Alan Turing, genius mathematician, master code breaker and father of modern computing, really die?

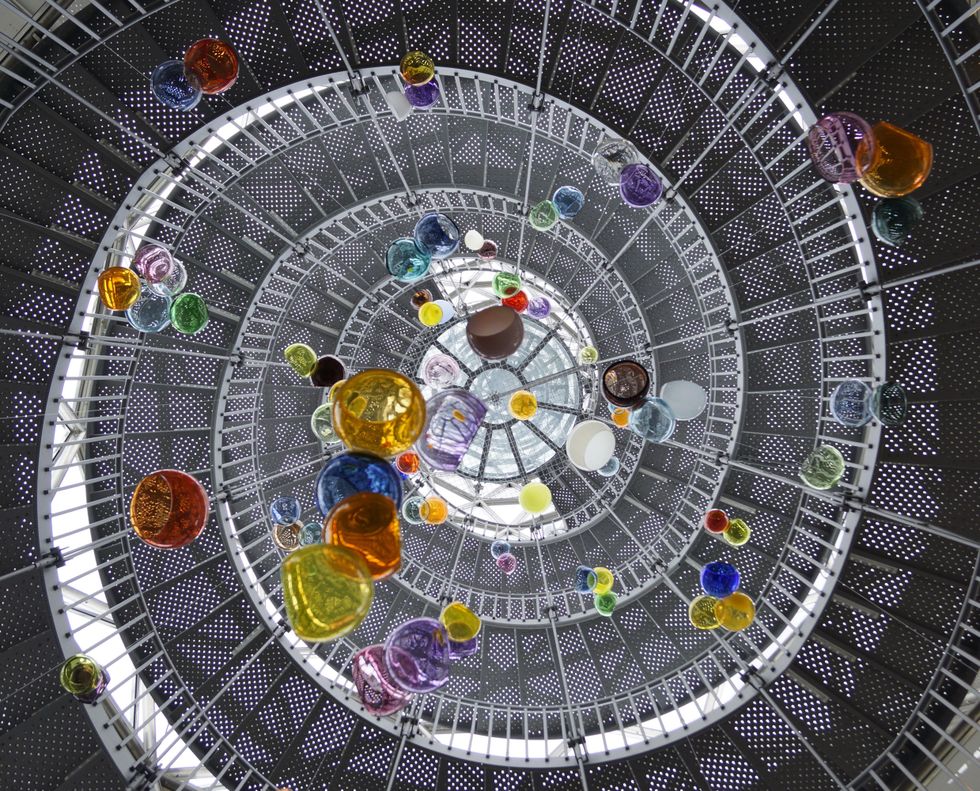

Of course, visitors to Houston's Hiram Butler Gallery, where the work is making its United States debut filling an entire room, will not likely see the 47 suspended, hallow glass orbs and immediately think about the man who broke the Nazi Enigma Code, and viewers are even less likely to ponder whether Turing’s death was suicide, accident or perhaps a state sponsored assassination. And artist Michael Petry quite likes it that way.

“What I’m trying to do is seduce you, with how beautiful and fun it is, to start asking questions,” he explained to me during a preview of the installation before it opened to the public on Saturday. “If you just shout at people with your work then they’re not going to listen.”

Primes

The work is indeed visually beautiful. The colored glass bubbles were original blown by artisan glassblowers as individuals or as a connected clusters of twos, threes, and fives, prime numbers. As they are hung from the ceiling of the gallery they appear to float in the air. Once I looked closer at their arrangement and discussed the creation of the work with Petry, I began to also see the mathematical beauty instilled within.

When I asked Petry for his belief, he simply said: “I think he probably was killed.”

Taking inspiration from Turing and guided by his own mathematics background, this Rice University graduate created his own algorithm to guide the glassblowers on the size, shape, transparency and color of the pieces. They reminded me of planets in a solar system or perhaps atoms forming molecules. Walking among them, which viewers can do at Hiram Butler but could not in the work’s first incarnation within the tower at the Glazenhuis in Lommel, Belgium, I almost felt like I was floating with them.

“I wanted these to have this notion of interaction and interconnectivity, where one is butting into another,” Petry told me, explaining his process and how the installation will change and become something new in each space. “Because they would interact and change over time, the constellation of them could change. It’s very important that it have that flexibility.”

The glass bubbles, which are not perfect spheres, but more like bowls or perhaps seem like someone has taken a bite out of each, also hold allusions to the black hole multiverse cosmology theory, that the universe is like a soap bubble. Or, as Petry explains in his artist statement on the work, “That each universe comes into being upon the gravitational collapse of a massive star, creating a black hole within its own universe, and a new universe within the multiverse.”

The Apple

All these scientific connections and allusions within the installation emerged later — perhaps not unlike a universe from a black hole — from Petry’s interest in Turing, with the AT in the title also being initials, and Turing’s death in 1954. His death that at the time was ruled a suicide via a cyanide laced apple.

Early in our talk, Petry walked me over to a single green, opaque orb, that of all the glass pieces most resembled a bitten apple, perhaps the greatest metaphorically loaded fruit. Think Eve and Adam’s bite from the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge or Good and Evil or even Snow White.

Turing’s death being a suicide does seems reasonable, after all this genius, unsung — at the time — hero of World War II was arrested and prosecuted for being gay, and then forced to undergo chemical castration to avoid prison. But there have been other theories, like that he might have accidentally inhaled cyanide during an experiment. That half-eaten apple was never actually tested. Some believe Turing was murdered for what he knew about Enigma. Still others believe that during the height of Cold War paranoia, he was killed by the Americans or British secret service so he wouldn’t defect to the U.S.S.R.

The hero was arrested and prosecuted for being gay, and then forced to undergo chemical castration to avoid prison.

“It’s really clear that they [the Soviet Union] would have taken Turing had he escaped to Moscow. If that had happened, then one of the greatest minds of the 20th century would have been making computers for the Communists,” Petry said, laying out the assassination theory. This led Petry to recap some fascinating trivia about modern spy deaths by radioactive sushi or poisoned umbrella tip.

The Assassination Question

When I asked Petry for his belief, he simply said: “I think he probably was killed.”

Still during our conversational travels from prime numbers to World War II, Cold War politics and spy craft to the edge of the universe, Petry came back to the idea that viewers need to experience the work for themselves and appreciate it on their own terms.

“When you look at it, you don’t actually have any idea that there’s some LGBT history involved in this. It’s not like there are any hanging testicles or willies,” he said, laughing.

Petry does want the work to pose questions and entice viewers to ask their own. “If you ask them a question, you’ve already gotten them open enough to say ‘Tell me more’ and then you can actually tell people even very difficult things.”

As we finished our talk, the late afternoon sunlight streaming through the large window in the gallery shifted and collected in that green apple-like piece Petry had pointed out earlier. Among all the other glass, it alone seemed to glow from within.