At the Arthouse

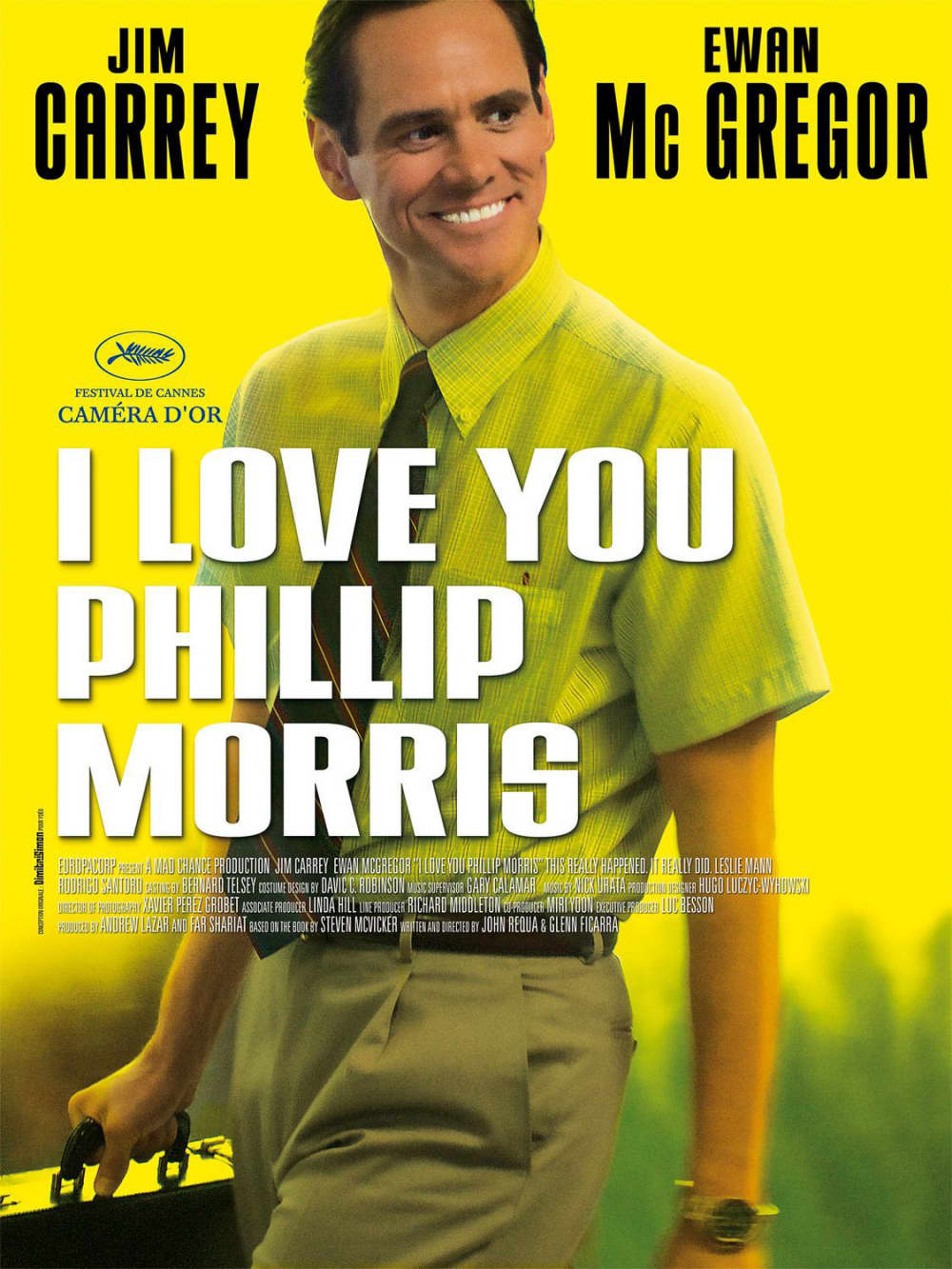

The hilarious tragedy of I Love You Phillip Morris: The love's in doubt, theCarrey con's not

Steve McVickerPhoto by Carolina Astrain

Steve McVickerPhoto by Carolina Astrain

The film version of long-time Houston writer Steve McVicker’s I Love You Phillip Morris took such a long time (several years) to get from Sundance into theaters that I was afraid that the filmmakers had done something to screw up McVicker’s book. It’s easy to imagine how they’d fail.

The story is non-fiction, but it’s about such a larger-than-life liar and brass-balled con man — who also happens to be a very big-hearted gay romantic — that his story is not believable, whether it really happened or not. The fact that rubber-faced and mercury-bodied Jim Carrey is playing said con man raises the stakes.

Never mind can Carrey play gay? Can he play a man in love? I’m still not sure about the answer to this last question, but never mind, because I Love You Phillip Morris is so entertaining that it should never have taken so long to find a distributor.

The film’s been largely well reviewed, but some critics have complained about its changes in tone. Is it a drama, a comedy, a farce, a satire?

I understand the questions, because it has elements of all four. (Somebody called it a “hilarious tragedy” — I like that.) First comes satire. Carrey’s Steven Russell, the lover of Phillip Morris, is a married man leading a conventional life in Georgia, when a car wreck causes him to question his entire life.

This questioning leads him out of the closet, but when he realizes that “being gay is expensive” he turns to crime. Fraud, that is. He doesn’t really want to hurt anybody, and you can understand why he’d think that pretending to be someone you’re not would be perfectly acceptable, if not socially encouraged, behavior. So the film at first plays as a send up of suburban hypocrisy and pretense.

The humor intensifies when he goes to prison; this second quarter or so of the film is by far its strongest, as it offers a witty, well-played take on how prison culture works, and how well a natural born con man like Russell can make out there. But when Phillip Morris arrives (he rented a car and forgot to return it), the tidy little satire moves on to riskier ground — the depiction of gay love (this specific gay love, that is) as an over-the-top, giddily, if not absurdly, romantic game of role playing. I say role playing, because it seems unlikely that Ewan McGregor’s Morris is a realistic depiction of any human walking the earth today.

Morris is a gay stereotype come to life, Blanche Dubois with a penis. McGregor would seem at least as natural saying, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers,” as Vivien Leigh ever did.

But — and this, for me is what makes the film work — McGregor absolutely sells his Phillip Morris in all his child-like vulnerability.

The scene where Morris and Russell have a romantic slow dance in their cell, while the rather scary prisoner in the next cell is beaten by the guards for refusing to turn off the music is weirdly brilliant.

The film loses a little fizz after they get out, though it still has strong moments. Carrey’s cons get progressively more outrageous. (When he tricks a Houston company into hiring him as its CFO, you can’t help but think of Andy Fastow and Enron.) For one thing, Morris has absolutely nothing to do but wait for disaster to strike when Russell is found out.

The film raises some provocative questions that co-directors Glenn Ficarra and John Requa (Bad Santa) aren’t altogether successful in answering. Can we really call Russell's devotion to Morris “love,” when it inevitably leads to his return to prison —for crimes he didn’t commit?

If the film had an answer for that, it might be great instead of highly entertaining. But that kind of depth and insight appear to be beyond Carrey’s reach. When the film is at most painfully emotional, I was always aware that I was watching Jim Carrey, the famous comedian, emote. Not so with McGregor, who always seems real.

Still, I Love You Phillip Morris is just about the best time a grown up can have at the movies right now.