One Singular Sensation

A Chorus Line changed the way we think about dancers forever

Michael Gruber, center, as Zach and the cast in the national touring productionat the Hobby Center.Photo by Paul Kolnik

Michael Gruber, center, as Zach and the cast in the national touring productionat the Hobby Center.Photo by Paul Kolnik The cast in line. Updating the show isn't really a concern for director BaayorkLee. "What's changed are the dancers. They spin faster, jump higher and sing onpitch," she says. "We started the triple threat term. After Chorus Lineeverybody needed to act, sing and dance."Photo by Paul Kolnik

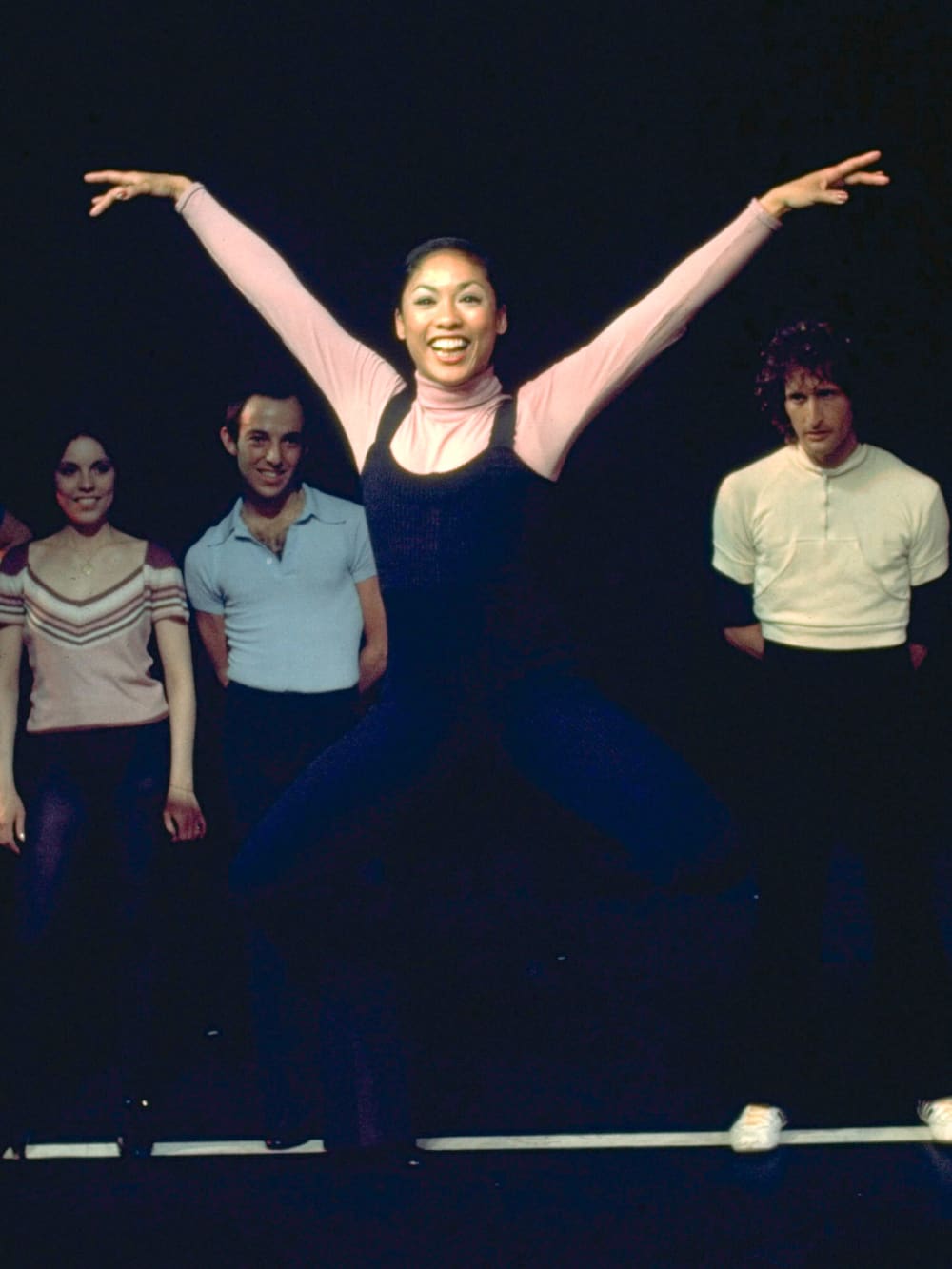

The cast in line. Updating the show isn't really a concern for director BaayorkLee. "What's changed are the dancers. They spin faster, jump higher and sing onpitch," she says. "We started the triple threat term. After Chorus Lineeverybody needed to act, sing and dance."Photo by Paul Kolnik Lee has directed several productions for Theatre Under the Stars. "I loveHouston, I've done some serious Tex Mex eating there," she quips.Photo by Martha Swope

Lee has directed several productions for Theatre Under the Stars. "I loveHouston, I've done some serious Tex Mex eating there," she quips.Photo by Martha Swope The story of casting the recent Broadway revival of "A Chorus Line" ischronicled in the 2008 documentary film, "Every Little Step."Photo by Paul Kolnik

The story of casting the recent Broadway revival of "A Chorus Line" ischronicled in the 2008 documentary film, "Every Little Step."Photo by Paul Kolnik

Rummaging through an old issue of Dance Magazine from the early 1970s, I found an interview with Michael Bennett. He had just finished Promises Promises, a huge Broadway hit. He wondered if he was done, if that was it, if he would be a one-hit wonder. He had no idea what would come next.

I wanted to whisper through the yellowed pages, "Michael, relax, you are going on to create A Chorus Line, the longest running musical in Broadway history. It will change the way we think about dancers forever. You will win seven Tony awards and the Pulitzer prize. You will be known as the father of the "dansical" and pave the way for Moving Out, Contact and other dance-based musicals. It will be big.

How's that for "what's next?"

Bennett holds a special place in my heart for two reasons. First, he's from Buffalo, my hometown. He studied with the legendary Beverly Fletcher and went on to become Buffalo's most famous dance son. Second, he told the real life stories of my tribe, dancers. A Chorus Line was culled from interviews with real life Broadway gypsies. Bennett gathered a room full of dancers and turned on a reel-to-reel tape recorder. At one point he says into the microphone, "Our lives are interesting, there could be a show here, and it will be called A Chorus Line."

Bennett holds a special place for Baayork Lee too, who is in town directing A Chorus Line for Broadway Across America at the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts. The role of Connie was based on her life. "I was the short Asian who wanted to be ballerina. Who would want to hear about that? Yet, Michael thought my story needed to be told," remembers Lee. "It was great. I didn't need to act, i just had to be myself."

Dance boomed in the 1970s. "Jane Fonda had everyone even dressing like dancers with leg warmers, dance bags and leotards," recalls Lee.

Lee went on to see many a Connie tell her story. "Early on, I remember spending too much time with the role and realized I was losing sight of the whole. I was an unemployed Broadway dancer then, I am not that girl anymore. I am a director and choreographer."

Houston has seen many of Lee's works. She directed The King & I, Bombay Dreams and another company of A Chorus Line for Theatre Under the Stars (TUTS). "I love Houston, I've done some serious Tex-Mex eating there," she quips. "Bill White even gave me the key to the city on Asian Heritage Day."

At some point, Bennett wanted to move on to other things and handed Lee the reigns. A Chorus Line had become a huge machine by then, with simultaneous shows in Los Angeles, Chicago, Australia, London and New York. "Go east, be like Christopher Columbus," Bennett told her. "This show can be done anywhere, from a flat bed truck to a huge theater. The important thing is the people on stage. We have to know them, feel for them and understand what we do to get a job."

Updating the show isn't really a concern for Lee. It happened in the 1970s and it's still set in the 1970s. "What's changed are the dancers. They spin faster, jump higher and sing on pitch," Lee says. "We started the triple-threat term. After A Chorus Line everybody needed to act, sing and dance."

The story of casting the recent Broadway revival is chronicled in the 2008 documentary film, Every Little Step, where you get to see plenty of footage of Lee auditioning many a "Connie."

Like many, Lee wonders what Bennett might have gone on to do. He had a five-picture deal with Universal before he died in 1987. "He could have done anything, film for sure, maybe even politics. Michael was larger than life. He dreamed big. He was so ahead of his time. You know, A Chorus Line was the first reality show."

A contributing editor at Dance Magazine, Houston and Dance Source Houston, Nancy Wozny blogs at dancehunter.blogspot.com.