Cinema Arts Fest Insider

Not-so-silent movie: Klezmer musician scores with live soundtrack for classic film

As a violinist and composer specializing in klezmer, the infectiously spirited folk music introduced to America ages ago by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Alicia Svigals has made a career out of keeping traditions alive and thriving. And not just in concert halls and recording studios.

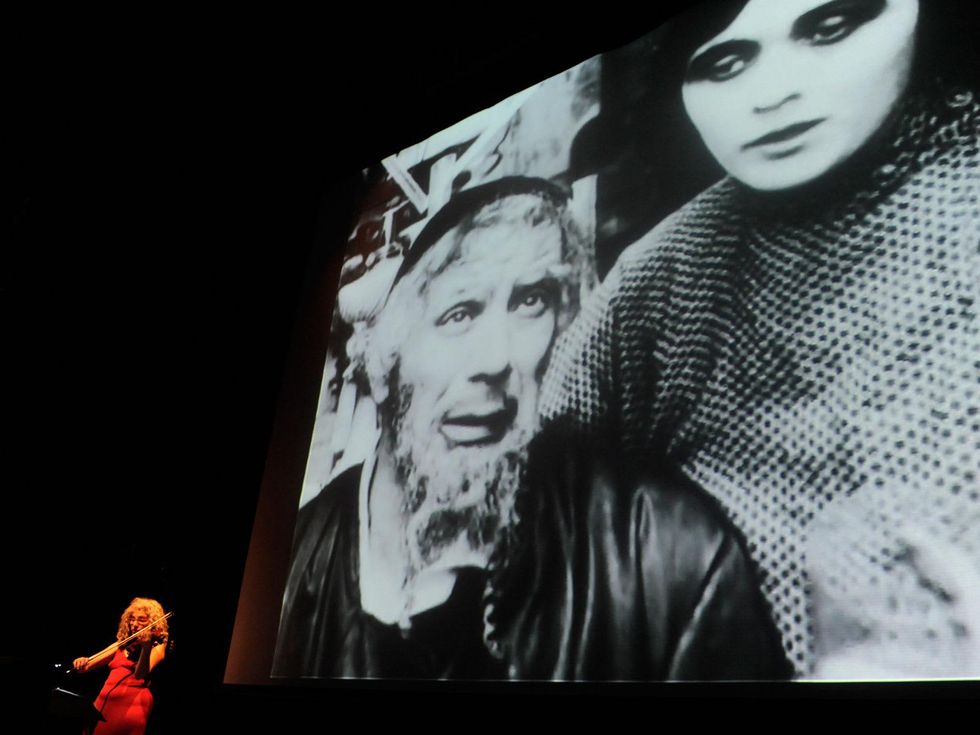

Two years, Svigals set out to restore the luster of a half-forgotten masterwork of silent cinema – The Yellow Ticket, an 1918 drama starring the celebrated Pola Negri — by composing a klezmer score every bit as fresh, vital and contemporary as the music she has performed both as a solo artist and with the Grammy Award-winning ensemble known as The Klezmatics.

Svigals will be on hand to perform that score (along with pianist Marilyn Lerner) when the Houston Cinema Arts Festival screens a newly restored version of The Yellow Ticket at 7:30 p.m. Thursday at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The HCAF presentation offers H-Town audiences both a unique opportunity to enjoy a silent movie with live musical accompaniment, and an invaluable object lesson in cinema history: The term “silent movie” actually is something of a misnomer, since even the earliest movies always were intended to be shown with some kind of musical complement, ranging from a lone pianist to a full orchestra.

"Women today are wearing toenail polish because of Pola Negri. That’s my favorite thing about her. When I go to the manicurist now, I think about her."

Or a klezmer duo.

Adapted from a Yiddish play by German filmmakers, and filmed on location in Warsaw, The Yellow Ticket details the often humiliating and sometimes downright dangerous experiences of Lea (Negri), a bright young woman who resides in the Pale of Settlement, a de facto ghetto for Jews in Imperialist Russia. As film critic/historian J. Hoberman explains, Lea resorts to deception in order to attend medical school in far-off St. Petersburg: She registers as a prostitute, thereby obtaining a “yellow card” that will allow her to travel unimpeded beyond the Pale.

“Studying by day, working (or rather avoiding work) in a brothel by night, she suffers the exposure of her double life and is driven to attempt suicide,” Hoberman writes. In the final scenes, however, Lea is providentially rescued and restored to respectability by a surgeon who turns out to be her long-lost father.

“The story isn’t much,” Hoberman allows, “but the movie has two great attractions — its captivating, kohl-eyed star and the several early sequences shot on location in Warsaw’s then-teeming Jewish district, the Nalewki. These sequences are likely the first time that the Nalewki was captured on film; many of the locals seemed amazed and fascinated to see a camera in their midst.”

During a recent telephone interview, Svigals admitted she had quite a similar reaction when she first laid her eyes on The Yellow Ticket.

CultureMap: So why is this silent movie different from all the other silent movies? What drew your attention to The Yellow Ticket?

Alicia Svigals: [Laughs] The film just basically plopped into my lap. I didn’t know about it before I was asked [by the Jewish Community Center of Washington, D.C.] to write a score for it. So I checked it out to see if I was interested – and it did grab me on the first viewing. It’s a rare item – and it’s amazing. Watching those sets and the faces was like watching old photos of my great-grandparents come to life.

On a first viewing, it may seem like – how should I put it? – a naïve fairy tale. But when you watch it a couple more times, you realize that the filmmakers are a lot more sophisticated than they may let on. It’s kind of a modernist film that way. There’s all sorts of symbolism in it. And when you start peeling back the layers, you see even more. There are references in the imagery to the idea of the doppelganger. And it’s very complex and ambiguous in the way it deals with themes of Jewish identity and assimilation. The more you watch it, the more sophisticated you realize it is, even though it may look like just a melodramatic love story. And I found it compelling.

CM: You were fortunate enough to view a version of The Yellow Ticket digitally restored by film historian Kevin Brownlow.

AS: Yes. It’s the only one in the world that runs at the right speed, with the original intertitles accurately translated. And what’s really great is that, when it’s shown at the right speed, which a lot of silent movies unfortunately aren’t, you can better appreciate Pola Negri’s performance, and the subtlety of her facial expressions. She’s really acting. She says it all with her face. It’s pretty cool.

CM: So how does one go about composing a score for a silent film?

AS: There’s basically two ways to do it. One is the old-fashioned way, where you play along with it while you’re seeing it for the first time ever, with an audience. And that produces a musical experience for the audience that basically reflects their understanding of things as [the film] goes along. The other way to do it is more like scoring is done now for any kind of film – which is much more premeditative, where the music can align more with the point of view of the people who made the film, so you can foreshadow things. Because you’ve already seen the film, and you know things that audience doesn’t know. And you can do something emotionally effective that way. And you guide the audience in what they should be feeling, which might be different from they could feel without music.

So I must have watched the film about a hundred times. I played along, and sang along, played the piano and the violin – and I recorded myself doing it until I hit on the right tone for each scene. Because to me, that’s what it was all about – tone – and what emotion I wanted to convey for each scene.

And it was tricky, because sometimes I wanted to straddle a few different feelings, and get them all across in the same scene. I tried to do that by taking some of the themes I introduce in earlier scenes and sort of weaving them together, or restating them in a new way. There’s one scene toward the end where I have three of the previous themes going at the same time, but with different aspects than they had before, all relating to each other.

CM: After watching the film so many times, have you become a fan of Pola Negri?

AS: I have done some research on her. And it’s interesting: In her memoirs, she wrote about making this movie. And she said part of her motivation was to combat anti-Semitism. Which is an easy thing to say now. But back then, that was kind of a progressive thing for her to say. And to do.

This is a very different role for her to play, compared to what she ended up playing later in her career. She was always known as a kind of femme fatale. She created that trope, almost, in American cinema. But in this film, she’s this young, naïve, innocent, studious Jewish girl who hopes to be a medical school student. It’s a completely whole other look for her.

Later, of course, she was quite another character. The lover of Rudolph Valentino and Charlie Chaplin at different times. She would walk a cheetah down the streets of Hollywood. And she supposedly invented the practice of wearing toenail polish. Women today are wearing toenail polish because of Pola Negri. That’s my favorite thing about her. When I go to the manicurist now, I think about her.

Alicia Svigals will be on hand to perform thescore (along with pianist Marilyn Lerner) when the Houston Cinema Arts Festival screens a newly restored version of The Yellow Ticket at 7:30 p.m. Thursday at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.