Back to the Future

PBS president Paula Kerger positions public TV for the digital age

Among the shows Kerger DVR's is "American Masters."

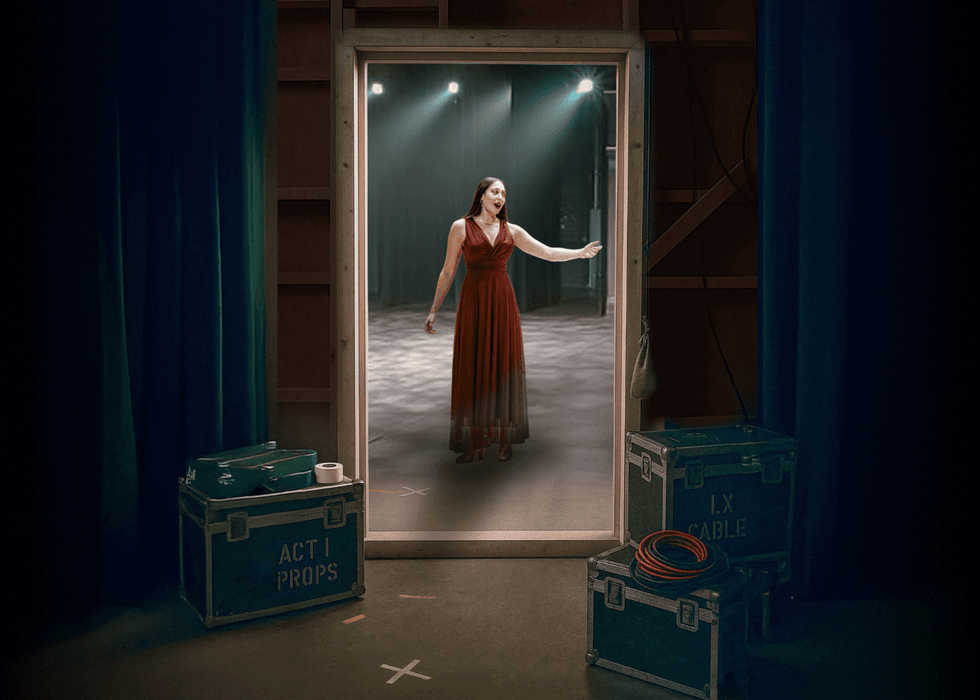

Among the shows Kerger DVR's is "American Masters." PBS president and CEO Paula Kerger, right, visited with Channel 8 staff duringher visit to Houston.

PBS president and CEO Paula Kerger, right, visited with Channel 8 staff duringher visit to Houston. Since taking over the head job in 2006, Kerger, shown her during her Houstonvisit this week, has emphasized links to the web.

Since taking over the head job in 2006, Kerger, shown her during her Houstonvisit this week, has emphasized links to the web. Kerger hopes to adapt some Channel 8 innovations that combine TV and socialmedia, like the recent Bone AppeTweet interactive food show

Kerger hopes to adapt some Channel 8 innovations that combine TV and socialmedia, like the recent Bone AppeTweet interactive food show Katy Perry was too sexy for "Sesame Street"

Katy Perry was too sexy for "Sesame Street" The NPR firing of Juan Williams threatens public funding of all publiclysupported media.

The NPR firing of Juan Williams threatens public funding of all publiclysupported media. A PBS documentary on John Lennon, with rare footage, will be shown on Nov. 22.

A PBS documentary on John Lennon, with rare footage, will be shown on Nov. 22.

Since taking over as president and CEO at PBS in 2006, Paula Kerger has been furiously positioning America's public television system for the digital age. Just this week PBS revamped its national website to include more content from affiliate stations like Houston's Channel 8.

A new free IPad app, with a sneak preview of its new series, Circus, has been a runway hit, along with products like an online video player that features more than 4,700 hours of programming and a subscription-based children's teaching tool for home and classroom.

During a whirlwind Houston visit, where she met with Channel 8 staff, donors and UH president Rena Khator, Kerger was intrigued by the station's BonAppeTweet foodie fundraiser Wednesday night in which viewers were encouraged to tweet their observations while watching the show.

"These are the kinds of experiments that we are looking to share across the country," Kerger said during an interview with CultureMap at the PBSHouston offices on the UH campus. "I want to get a good sense of what's going on here and also talk about some of the other challenges and opportunities ahead. The best way to do that is communicate a lot."

CultureMap: What are the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for PBS?

Paula Kerger: Obviously the biggest challenge is financial. I'm not sure there is an organization, corporate or not-for-profit, that wouldn't say the same thing. These are obviously complicated times for all of us. But the opportunities are enormous — to not only build programs of compelling content but distribute them in so many different ways. From my perspective this is really a great big sandbox to try to figure out with the power of all this technology, what we can do to really serve the American public.

We're also focusing on the arts. In this crowded media environment, nobody is doing arts. There are wonderful cable organizations who tried hard — A&E, Bravo — but couldn't make it work. We have a great documentary coming up on John Lennon in a few weeks (Nov. 22). There's been a lot of material on John Lennon; there will be nothing like the documentary that we have, with a lot of footage that Yoko had, along with never-seen-before footage that really talks about his New York days and his music. That's how we're different from some other media organizations.

CM: How do you compete against an HBO and other cable networks?

PK: We're in every home; HBO is a premium service and is certainly not in every home. The amount of documentaries we air on a regular basis is significantly greater than HBO. HBO does some really great work. Outside of documentary work, their John Adams series was extraordinary. I would have been proud to have it on public broadcasting. But we have a significantly larger footprint and a deeper commitment to bringing an independent voice. Because that's our reason for being.

CM: In a recent interview with the Financial Times, you talked about working closer with NPR on a national and local level. Are you doing that?

PK: We are. In a period when many news organizations are shuttering their foreign operations, NPR is actually expanding theirs. They have a great reporting structure which we use. Programs like News Hour and Frontline work in partnerships. Those journalists who are involved with News Hour and Frontline also appear on NPR.

So we're looking at ways to share content. On the web, we are building content together. Most people recognize there is a relationship between public radio and public television here (in Houston). They are in the same building. So to be able to pull that together is important.

CM: Do you see a merger taking place?

PK: I don't, though, you just never know where the future lies. But at the present time both of our organizations bring something very different and unique to the table. We've operated pretty well separately.

CM: Sometimes people tend to blend the two, like during the NPR/Juan Williams flare-up. Do you get brushback when things happen at NPR?

PK: Within our own public media family, it happens on both sides. If something happens on public television, public radio gets it as well. I remind people that we are separate, but at the same time we share a common mission, which is to serve the American public.

CM: But how do you handle something like that?

PK: With the current case with NPR, anyone that has any editorial questions really should address them to NPR. I do think it is unfortunate, though, that when situations like this happen, those who are interested in defunding us seize upon these as excuses. And that concerns me a great deal.

CM: What's your best case pitch to someone like Sen. Jim DeMint, who plans to introduce a bill to abolish public funding for public broadcasting?

PK: I would say to him that he should talk to his constituents because every year for the last seven years the Roper organization has conducted a poll and it has asked a whole series of questions about the value of public media. The American public believes that PBS is the best use of tax dollars, second only to our national defense.

And when asked is too much money going to public broadcasting, the vast, vast majority says no. They either say it's about enough or more should be going into public media. In most parts of the country, the only remaining locally owned and operated broadcasters are the public stations. We play such a critical part and legislators need to pay attention to that.

CM: When a Sesame Street segment with Katy Perry was recently removed because she was deemed too sexy, it got a lot of attention.

PK: It did get a lot of attention. The producers of Sesame Workshop recognized that moms were concerned and so it didn't appear as part of the program, but it was on YouTube so adults could see it. I thought it was funny. And it got a lot of people talking about Sesame Street.

CM: Do you have a favorite show?

PK: (laughs): Don't ask me that. I do, but I feel like you're asking me to pick my favorite child.

CM: What do you DVR?

PK: You're sneaky. I like the range of programming we have on public television. I love Frontline. I feel that is a series that defines public media in many ways. I'm very interested in the arts. I love the work that comes from our producers, both the performances themselves as well as American Masters. I'm very interested in science, so NOVA has always been an important part of my viewing habits.

CM: What role due to see Channel 8 playing in the national picture?

PK: It's a very special station because it was the first. I see them as a great innovator. For a station to try and experiment to really engage the community around content is something that I want to see other stations do. I see 8 as a example to other stations of what can be done to really leverage the relationship of national content that we produce while making a powerful impact locally. That's why I'm really happy to be here this week as we look at other ways to build that local/national model.