We’re officially in the home stretch, and Christmas is just around the corner.

Before that, this weekend offers plenty of holiday-themed events, including an ugly sweater party/toy drive and a yuletide visit from Pentatonix. But some fascinating visual art is also popping off this weekend, from an intriguing art exhibition to several movie screenings, including the latest from hometown boy Richard Linklater.

Or, you could pick up some booze over at O.S.T. Liquor, get lit, and sing “Luv Ya Blue” over and over again – just a suggestion.

Thursday, December 18

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston presents Music at the Museum

Music at the Museum is back, as CAMH wraps up the year with an evening of live music, an art workshop, and contemporary art. Jupiter will be spinning house, ambient, club tracks, and more. And you can participate in the cyanotype workshop downstairs. Join CAMH FAQ team member and artist Carlos Mendoza in this hands-on activity that bridges car cultures from the West Coast to H-Town. 6 pm.

Sabine Street Studios presents "Zuzu's Petals" opening reception

Sabine Street Studios’ end-of-the-year exhibition, “Zuzu’s Petals,” takes inspiration from the beloved 1946 classic film, It’s a Wonderful Life. The group exhibition of mixed media works offers an opportunity for reflection on the year that has passed, the promise of the new year ahead, and the meaningful memories that weave through our lives. The reception will include complimentary beverages and snacks, as well as brief artist talks where each creator will share insights into their work and its significance within the exhibition. 6 pm.

Aurora Picture Show presents Aurora Holiday Party & Raffle

Join Aurora Picture Show’s famously festive, annual holiday party – the first one held in the new Navigation Blvd. space. This free event features beverages provided by Double Trouble and Saint Arnold, light bites from Phoenicia, vintage holiday TV projections, and music provided by DJs Gracie Chavez, Marcelluz Gualez, Alex la Rotta, and Peter Lucas. The raffle, benefitting Aurora’s artistic and educational programming, is open until 9 pm and features an array of great items, experiences, and gift cards. 7 pm.

Friday, December 19

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston presents Nouvelle Vague

Nouvelle Vague, Richard Linklater’s love letter to the revolutionary magic of the French New Wave, reimagines the making of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960). As a Cahiers du Cinema critic, Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) turns to filmmaking with a mix of fresh faces and daring talents that bring his spontaneous, idiosyncratic film to life. Capturing the behind-the-scenes creative chaos at the heart of one of cinema’s most iconic and influential debuts, catch this movie at the MFAH this weekend – in glorious 35mm! 7 pm (5 pm Sunday).

Rice Cinema presents The Projectionists’ Reel

Rice Cinema will have a special screening featuring work by Tish Stringer, a Rice alum and former technical exhibition manager at Rice Cinema. In The Projectionists’ Reel, Kirston Otis spins the tale of how crafty projectionists of the Greenway Theater cannibalized cinematic ephemera into remix joy. Preceded by a bonus screening of We’re Not Judges, a short film by Renée Feltz, a former KPFT News Director, and currently at Democracy Now! The filmmakers will be in attendance for a post-screening Q&A. 7 pm.

Houston Symphony presents Elf in Concert

Buddy (Will Ferrell) was accidentally transported to the North Pole as a toddler and raised to adulthood among Santa’s elves. Unable to shake the feeling that he doesn’t fit in, the adult Buddy travels to New York in search of his real father (James Caan). After DNA test confirmation, Buddy and his dad build a relationship with chaotic (and comedic) moments. The heartwarming tale of Buddy the Elf will play on the big screen, while every note of John Debney’s score is played live to picture. 7:30 pm (2 pm Sunday)

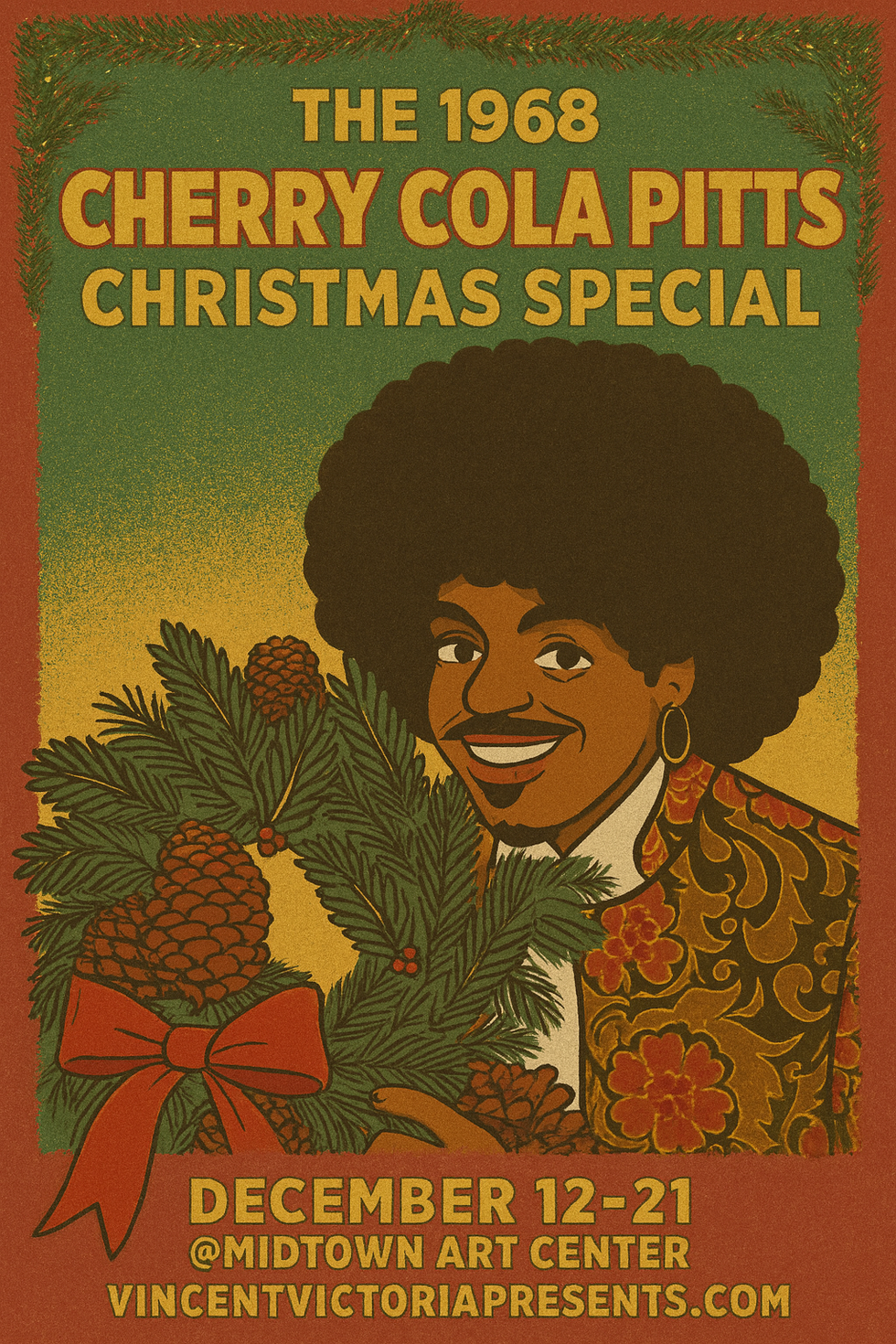

Vincent Victoria Presents The 1968 Cherry Cola Pitts Christmas Special: A Musical

Vincent Victoria Presents delivers the world premiere of a new stage production, The 1968 Cherry Cola Pitts Christmas Special: Christmas Will Never be the Same. The production, a sharp, irreverent, joyously queer holiday biting satire set in the explosive year of 1968, stars Cherry Cola Pitts, an openly gay entertainer navigating fame, freedom, and chaos under the studio lights. 8 pm (3 and 8 pm Saturday; 3 pm Sunday).

Saturday, December 20

O.S.T. Liquor Store presents the Annual Holiday Bourbon Allocation

O.S.T. Liquor Store will launch one of its largest and most anticipated bourbon allocation releases, offering more than 200 rare and highly coveted bottles to collectors and holiday shoppers. The event is known for drawing enthusiasts from across the Houston area who are seeking hard-to-find bourbons, whiskeys, and limited-edition spirits to raise the bar on gifting and entertaining this holiday season. Get there early. 10 am.

BLCK Market Holiday Festival at East River

Step into a festive celebration of Black-owned businesses at the BLCK Market Holiday Festival at East River. Attendees will enjoy holiday shopping at its finest as East River transforms into a bustling winter market filled with music, merriment, and unique finds. Browse curated gifts (seasonal décor, art, skincare, books, and candles), dance to the beats of live DJs, and get grub at food trucks – all while being surrounded by the joyful energy of community. Santa and Mrs. Claus will also be available for photos from 12-2 pm. 11 am.

Pentatonix in concert

In 2011, a cappella group Pentatonix became the first act to top both the Holiday Albums and Holiday Songs charts simultaneously. Since then, Christmas has become their business, dropping such seasonal releases as 2014’s That’s Christmas to Me and 2016’s A Pentatonix Christmas. They’ll be Houston as part of their Christmas in the City tour, performing favorite songs from their seven holiday-themed albums, including the new Christmas in the City. 7 pm.

Winsome Prime presents Annual Ugly Sweater Christmas Party & Toy Drive

The Southern-inspired steakhouse is kicking off the holiday week with its annual Ugly Sweater Christmas Party & Toy Drive. Attendees are asked to bring a new toy to benefit the Isiah Factor Christmas Toy Drive, as well as dress in their most outrageous, over-the-top holiday sweaters for an ugly sweater contest, with special perks, giveaways, and photo moments throughout the event. 7 pm.

Sunday, December 21

Kings Harbor Waterfront Village presents Holiday on the Harbor

Join Lake Houston mixed-use development Kings Harbor Waterfront Village as it celebrates the holiday season with Holiday on the Harbor. Attendees can enjoy a free photo opportunity with Santa and Mrs. Claus, music from a DJ, face painting, an on-site caricature artist, and riding on the trackless train. Families can also play yard games and create holiday crafts, making it a day full of holiday cheer for kids and adults alike. 1 pm.

Houston Cinema Arts Society and Houston Film Commission presents Luv Ya Bum!

Luv Ya Bum! is more than a sports documentary – it’s a testament to the power of leadership, community, and the enduring impact of legendary Houston Oilers head coach Bum Phillips. River Oaks Theatre will have a screening, presented by Houston Cinema Arts Society (HCAS) and Houston Film Commission, complete with a post-screening conversation with the producers. A special exhibition will be on display, courtesy of the Museum of the Gulf Coast, featuring a remarkable collection of personal effects and historical artifacts. 2 pm.

The Houston Tidelanders present Yule-Tide Carols

The Houston Tidelanders will ring in the holiday season with their show, Yule-Tide Carols. The tradition brings Christmas to life through the four-part harmonies of barbershop a cappella singing. The Tidelanders will perform a mix of classic Christmas favorites and fresh new arrangements, from the peaceful beauty of “O Little Town of Bethlehem” to the inspiring message of “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day.” 4:30 pm.

Photo courtesy of Pentatonix