Pop Art Painting by numbers

From South Houston to Bennifer & back: A reinvented, celeb-mag free Trey Speegletakes flight at Koelsch Gallery

Trey Speegle at a recent opening of his work at Koelsch Gallery

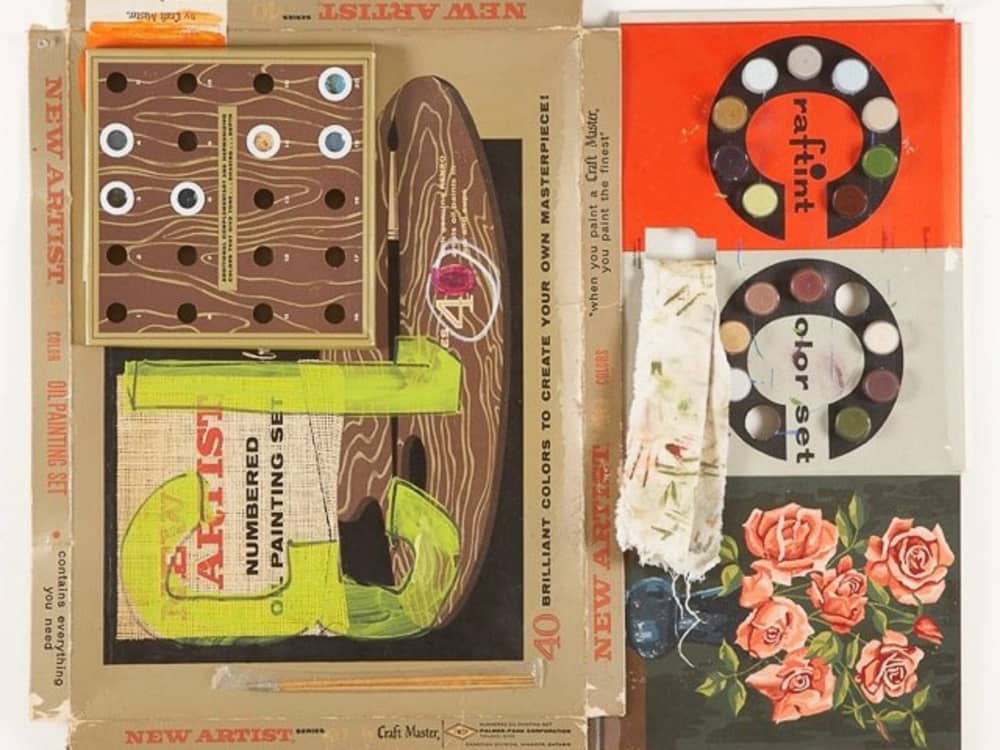

Trey Speegle at a recent opening of his work at Koelsch Gallery Trey Speegle, "Hi," 2009

Trey Speegle, "Hi," 2009 Trey Speegle, "13 Roses" (family matters), 2009

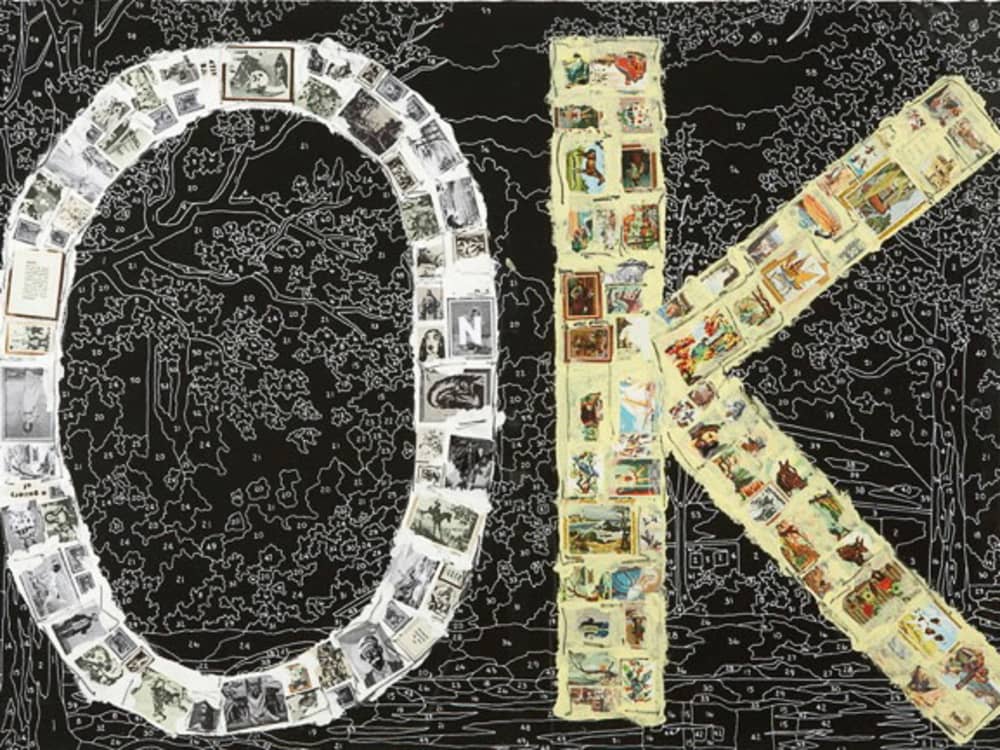

Trey Speegle, "13 Roses" (family matters), 2009 Trey Speegle, "OK," 2007

Trey Speegle, "OK," 2007 Trey Speegle, "if... then...," 2009

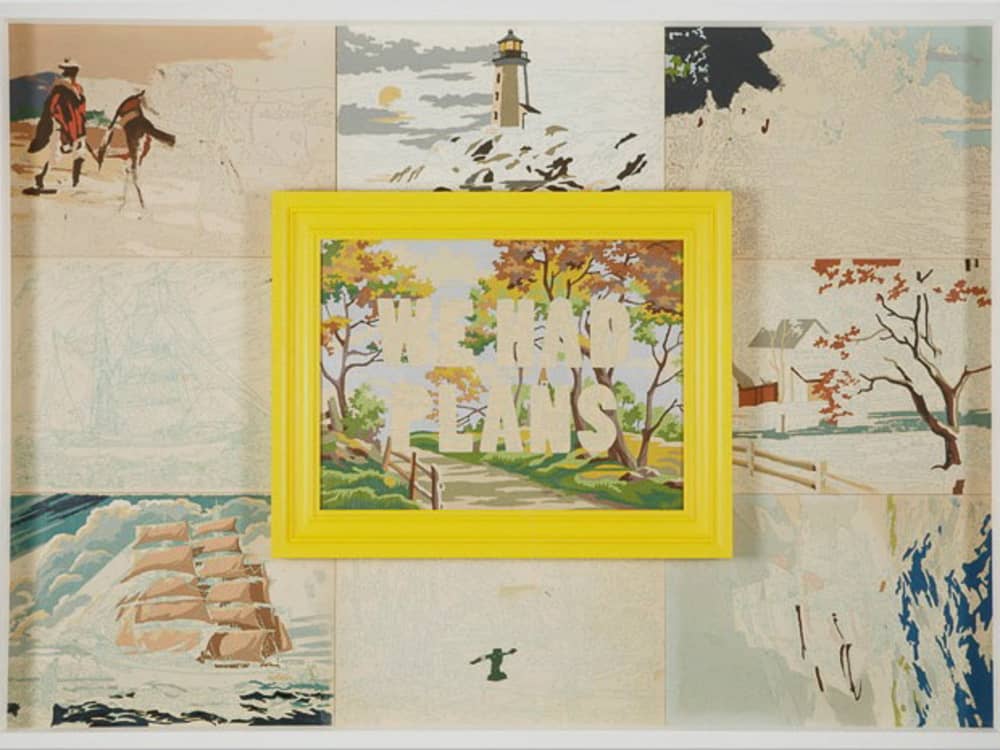

Trey Speegle, "if... then...," 2009 Trey Speegle, "We Had Plans," 2007

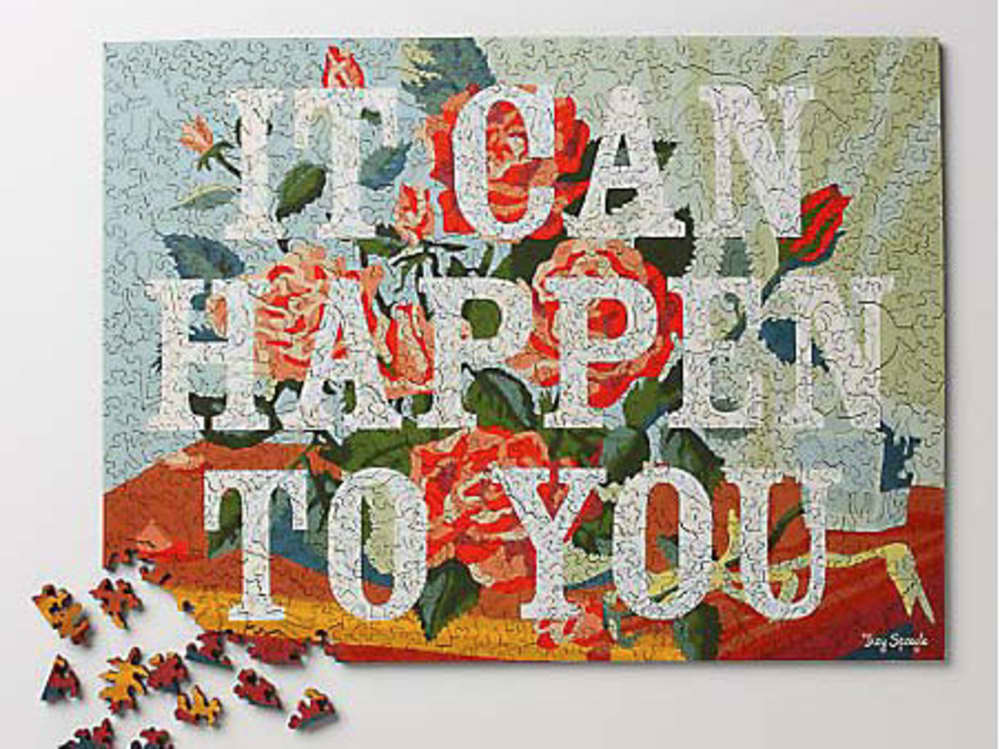

Trey Speegle, "We Had Plans," 2007 "It Can Happen To You" puzzle by Trey Speegle for Anthropologie

"It Can Happen To You" puzzle by Trey Speegle for Anthropologie "Honest" plate by Trey Speegle for Anthropologie

"Honest" plate by Trey Speegle for Anthropologie Speegle working on the backdrop for the Stella McCartney fashion show

Speegle working on the backdrop for the Stella McCartney fashion show "Yes" for Stella McCartney

"Yes" for Stella McCartney

Trey Speegle is coming into his own.

For decades a prodigy of the magazine publishing industry (his resumé includes stints as the designer and art director at such magazines as Vanity Fair, Vogue and Us Weekly), the native Houstonian is now striking out on his own, exploring the surface and depths of a paint-by-number-inspired Pop Art. Having applied his artwork to such commercial undertakings as the set of Stella McCartney's spring 2010 runway show and a prolific collaboration with Anthropologie, Speegle is now teaming with the Heights' Koelsch Gallery to provide his hometown with a glimpse of his punchy paint-by-number assemblages.

The flurry of output might sound manic, but that's authentic Speegle making good on his promise to expand art audiences.

"I really don't like how art is segregated from everyday life in the world," he stresses. "It's so rarified."

Speegle's journey from South Houston high schooler, to the creative king of New York's magazine empires and now a serious studio artist has been characterized by a series of wise moves and incredulous conviction. He began working at the Francois de Menil-owned luxury lifestyle rag Houston City magazine while still in high school, rising to the level of art director at the age of 19 before he whisked himself away to New York.

Once there, he ingratiated himself in the magazine publishing community, capitalizing on key moments at myriad publications, like working at Vanity Fair during its 1980s revival and first "Hollywood Issue," and directing Us Weekly's look during the peak of "Bennifer" and early 00's teen pop culture — it was Speegle who curated the rise of Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera and many a boy band.

Ever since his arrival in New York during the twilight of his teens, Speegle has relished walking the line between fine art and commercial acclaim. While working as a graphic designer in the 1980s for Pat Hearn's gallery, he enveloped himself in the city's club scene, befriending East Village artists the likes of Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf. He began making his own flavor of Pop, particularly portraits of such Houston society stalwarts as Carolyn Farb, Lynn Wyatt, Joann Herring and the Baron and Baroness Enrique di Portanovas.

"The last one — they're done now, but his name was Enrique and Sandra was this really hotsy-totsy, giant boobs gal. They lived on River Oaks Boulevard and everyone called them 'Ricky and Buckets,'" Speegle recalls of the era's reigning RO couple. The Houstonian series culminated in a 1981 gallery exhibition entitled Re-Pop.

"It was kind of like this Houston-based Warhol treatment," he says. "It's something that would go over big now."

Banking on the Bayou

Despite a mastery of Manhattan, Speegle's connection to his Houston heritage goes beyond the just-revealed show at Koelsh. In recent years, he's reconnected with his journalism teacher from South Houston High School (ironically nicknamed "SoHo"). Although his repertoire includes the industry's glossiest publications, he attributes his success to the guidance of that teacher, Diane Stafford, who is now a published author herself working in California.

Now, the two are working on a collaborative book: A fictionalized version of the late 1970s Houston high school experience, with each party trading off writing chapters in his and her particular voice.

The upcoming novel speaks to both Speegle's natural affinity for networking and an expanding sense of self-reflection.

"I spent a lot of my career working on other peoples' projects," he explains. "I put a lot of energy into that, and now I'm at the point where I'm turning away from other peoples' ideas, and focussing on my work and my career to make it flourish.

"I don't work for magazines anymore," he tells CultureMap, repeating twice, "I'm done with magazines."

Gone are his days at such celebrity-obsessed publications as OK! and Radar, as Speegle finds himself working exclusively as an artist now. "I've had enough of celebrity culture for awhile," he declares.

As part of his career's sea change, he recently signed with a new gallery in Chelsea, Benrimon Contemporary, which will be exhibiting a preview of his work in September to introduce his work to collectors, followed by a solo show in February 2011 featuring large-scale works in which he'll be delving deeper into the underpinnings of his paint-by-number works.

With a collection of over 2,500 original paint-by-number sets, Speegle has fetishized what The New York Times calls the "tribal art of 20th-century American suburbia."

His own holdings began with the inherited collection of friend and Saturday Night Live chief writer Michael O'Donoghue, leading to involvement in a 2001 exhibition at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, Paint By Number: Accounting for Taste in the 1950's, to which Speegle lent 20 works. He surmises that audiences are now fond of paint-by-number as faded emblems of a pre-ironic America.

For his own reinterpretations of paint-by-number, the artist expands the proportions and superimposes recognizable words and phrases.

Take his "Yes" piece for the Stella McCartney show, in which he blew up a vintage paint-by-number depiction of the Arc de Triomphe, adding the word "Yes" in gigantic capital letters — by expanding the original work's dimensions, applying a splashy palette and taking it out of its context and into a fashion show, Speegle makes the work his own.

He intends for his subversive, Ed Ruscha-esque words and phrases to spark a variety of interpretations — in this case, the word may refer to the political triumph the original architecture represented, the confidence of McCartney's collection, or if an observer were to carefully connect the dots, it could be paying homage to Yoko Ono and the Lennon-Paul McCartney connection.

"I love Yoko," Speegle says of the conceptual artist, famous for her original "Yes" piece. Nobody along the catwalk spoke of the Yoko connection; it may have even gone unnoticed.

"If anybody has ever before made that connection, they didn't write about it in the press — and there was a lot written about that show," he says.

But Speegle thrives on just this type of playful cultural subtext. It's his way of bringing art and the everyday into one moment.

In fact, Speegle claims that his work isn't necessarily just about paint-by-number: "I'm re-contextualizing it and also using it as a jumping off point," he says, "Instead of being about paint-by-number, for me, it's about making art and making your life interesting. Paint-by-number is where banal and profound meet. Like the word 'Yes' that I did for Stella — unless you do something specific with the word, it's as banal as it gets.

"Depending on how you use that as an affirmation, empowering yourself with that word, it takes on a new meaning. It's based on the visual, and then the contact is really this clashing of the image and then this meeting of a phrase that you've heard a million times that can mean something new."

Art for fashion

And why shouldn't paint-by-number be connected to fashion? That cross-disciplinary mentality led Speegle to apply his artwork to domestic goods for Anthropologie with resounding success. The artworks are still on their pedestal (Speegle insists he's an artist, not a designer), but now open to new audiences.

"We would take an artwork and apply it — for a rug, we would break it down into a thread color palette and send it to a rug maker in India," he says. "It's a new message delivery system for a work."

Speegle's commercial bent connotes the current retail-oriented zeitgeist in fine art: We're in an age in which a superstar like Damien Hirst peddles his own prints and the works of others on his online store Other Criteria, while Larry Gagosian deals editions of his artists' work in a storefront on Madison Avenue. Speegle points out, "How many people go to a gallery to see an artist's show? Art shouldn't be like a Rolls Royce — you want it to be like a Chevy.

"I don't think my work's so much about paint-by-number as it is an entry point for people," he emphasizes. "With so much contemporary art, people don't know where they come in or how to relate to it. A lot of times people are intimidated by the idea of art in a gallery. When you go to a museum, you don't see people talking; they're wandering around like they're at Wal-Mart and don't know what they're looking for."

With Speegle's art for Anthropologie, shoppers can bathe, eat and sleep with his work.

His eye for quotidian objects caught the attention of design personality Jonathan Adler after Adler's partner and fashion director of Barney's, Simon Doonan - a friend of Speegle's for 25 years - spotted the backdrop to the Stella McCartney show. Continuing the same upscale commercial caché of his collaboration with Anthropologie, he's now partnering with Adler to put his below-$5,000 smaller items for sale in Jonathan Adler stores and online (Speegle predicts that an Adler storefront will hit Houston someday soon).

"With Jonathan, I'm branching out to reach a new audience — I like doing that," he says.

Fans of Speegle can expect to see a steady stream of these collaborations, like the Jonathan Adler line and an impending partnership with a top-notch New York-based department store for which he will be curating a catalogue and mounting his images in grand window displays.

While his career as a full-time artist is ricocheting from his studios in the Meatpacking District and upstate New York, in many respects he's come full-circle. No longer the captain of magazines, Speegle's work is now fodder for such publications, gracing the pages of Spanish Vogue, Nest and Gotham.

Completing this circle, Speegle recently found himself in his hometown for White Linen Night, installing what he calls a "mini Houston retrospective" at Koelsch.

"It's always different coming back to Houston because the city seems to be changing so fast," he says. "I no longer have family here, and now it's art that's bringing me back. The scene feels like it's more energized."

The Koelsch show is on view until September 18, but Speegle also has another Houston exhibition in the works, in which the artist will display his own works beside a collection by local artist Mary Hayslip. The proposed exhibition will also display collaborative work between the artists, who have shared a friendship for 30 years.

Not many renowned artists would count Hayslip, Warhol, a hometown high school teacher and celebrity fashion houses as among their greatest influencers, but Speegle's admiration does not obey any sort of hierarchy.

In an age in which hapless networking and cut-throat competition characterize both the publishing and fine art worlds, Speegle is eschewing calculating schemes by capitalizing on his assertive Pop visions and sharp conviction. As illustrated at Koelsch Gallery, the artist is reinventing himself mid-life and mid-career, bursting outside the lines of his own paint-by-number.