At the Arthouse

Love and death, French style: The Father of My Children packs a big surprise

Watching The Crying Game the other day, I was reminded of how challenging that movie was to review. It’s an amazing film that gave you plenty to think and talk about, and which repays repeated viewings. But, the first time you see it, the movie is all about its “surprise.” (For CultureMap’s younger readers, the film was an early gender-bender.) So the reviewer had to be careful about how much he revealed.

Likewise, The Father of My Children is a richly detailed and subtle film about familial love, business calamity, and the vagaries of life itself, but it too has a surprise, one that comes down like a cleaver about halfway through. I’ll try to tiptoe my way around the film’s secret and encourage you to see it at the same time.

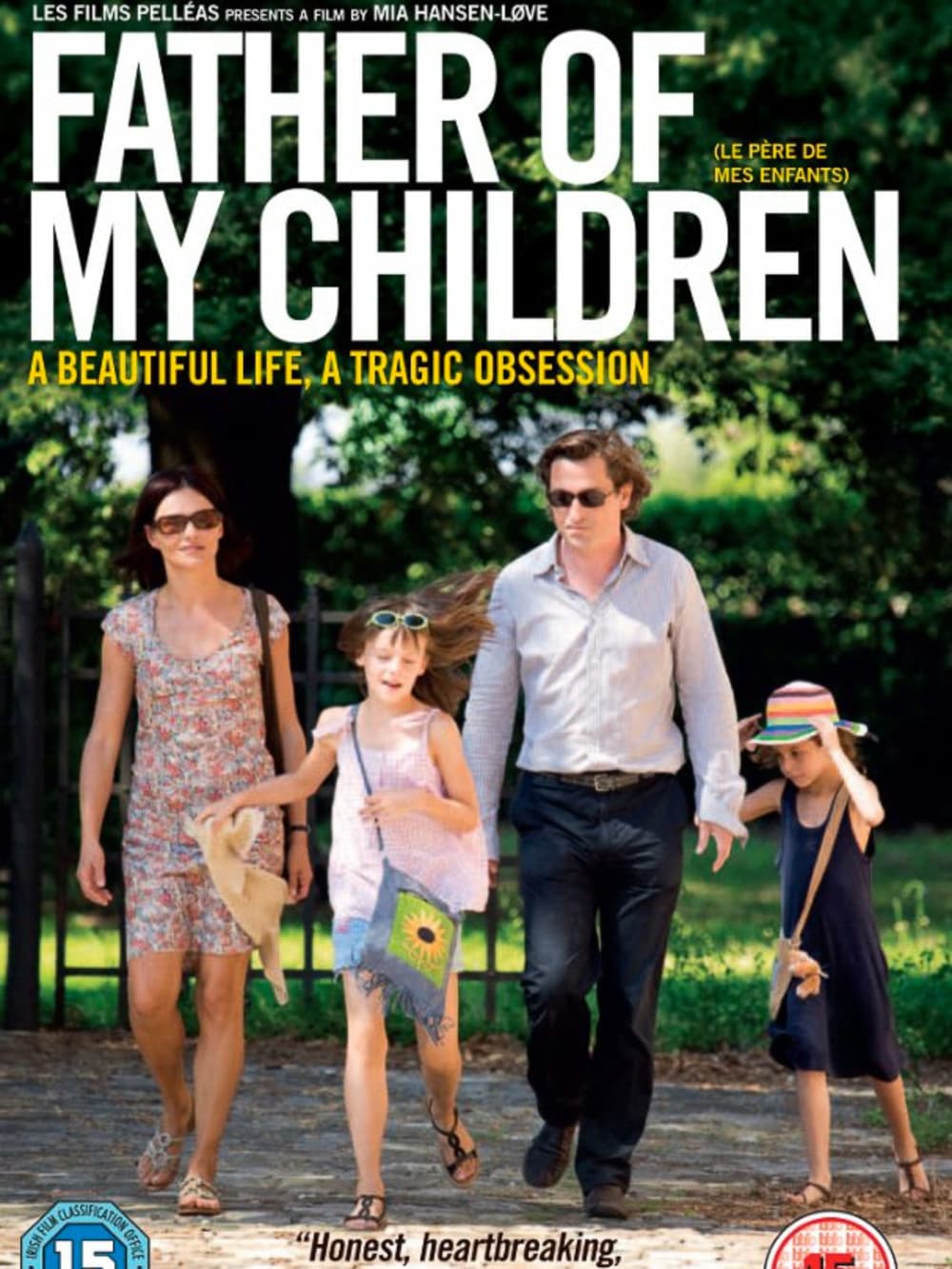

The film has a divided nature from the start. It begins with a display of charismatic French film producer Grégoire Canvel’s (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing) juggling skills. In his Paris office, calls and messages come streaming in, all of them carrying bad news about one shoot, or debt, or another. Grégoire is the focal point of so many crises that he has to talk simultaneously on two cell phones as he drives home to begin his weekend with his family: Sylvia, his Italian wife (Chiara Caselli), and his three daughters, including the teenaged Clémence (Alice de Lencquesaing).

This first half of the film has a tone that is much more foreign to us Yanks than is its language. The Father of My Children (which turns out to be an enigmatic title) appears to have the setup for either a comedy about a harried family man, or a crime story about how Grégoire has to kill someone to save his business. But writer-director Mia Hansen-Love never forces the story into a mold, instead letting it develop organically; the film comes out looking as if she had shot a tightly edited documentary.

The happiness of Grégoire’s family life looks like it should be enough to offset his business woes (who knew it was this hard to make independent films in France?). But the details pile up, quietly but inexorably, and then the cleaver falls.

The film then shifts gears. Instead of being more or less about the current economic crisis, it takes on a more timeless theme (though is there any theme more timeless than the one about artistic types needing more money?) about how a family responds to unexpected tragedy.

This is the part I can’t say much about. Let me just point out that, while this section of the film may be slightly less dramatic than the story of Grégoire’s business woes (Hansen-Love never forces us to whip out our hankies), it’s more revealing about character.

Those that the tragedy left behind, especially the wife and the eldest daughter, grow onscreen in arresting and beautiful ways. The way all of them pay express something like eternal love for the dead, while at the same time changing as individual people, is very moving, and makes the film feel startlingly real.